Chapter 12: Instrumental Variables

12 Instrumental Variables

12.1 Introduction

The concepts of endogeneity and instrumental variable are fundamental to econometrics, and mark a substantial departure from other branches of statistics. The ideas of endogeneity arise naturally in economics from models of simultaneous equations, most notably the classic supply/demand model of price determination.

The identification problem in simultaneous equations dates back to Philip Wright (1915) and Working (1927). The method of instrumental variables first appears in an Appendix of a 1928 book by Philip Wright, though the authorship is sometimes credited to his son Sewell Wright. The label “instrumental variables” was introduced by Reiersøl (1945). An excellent review of the history of instrumental variables is Stock and Trebbi (2003).

12.2 Overview

We say that there is endogeneity in the linear model

\[ Y=X^{\prime} \beta+e \]

if \(\beta\) is the parameter of interest and

\[ \mathbb{E}[X e] \neq 0 \text {. } \]

This is a core problem in econometrics and largely differentiates the field from statistics. To distinguish (12.1) from the regression and projection models, we will call (12.1) a structural equation and \(\beta\) a structural parameter. When (12.2) holds, it is typical to say that \(X\) is endogenous for \(\beta\).

Endogeneity cannot happen if the coefficient is defined by linear projection. Indeed, we can define the linear projection coefficient \(\beta^{*}=\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y]\) and linear projection equation

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=X^{\prime} \beta^{*}+e^{*} \\ \mathbb{E}\left[X e^{*}\right] &=0 . \end{aligned} \]

However, under endogeneity (12.2) the projection coefficient \(\beta^{*}\) does not equal the structural parameter \(\beta\). Indeed,

\[ \begin{aligned} \beta^{*} &=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y] \\ &=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[X\left(X^{\prime} \beta+e\right)\right] \\ &=\beta+\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X e] \neq \beta \end{aligned} \]

the final relation because \(\mathbb{E}[X e] \neq 0\).

Thus endogeneity requires that the coefficient be defined differently than projection. We describe such definitions as structural. We will present three examples in the following section.

Endogeneity implies that the least squares estimator is inconsistent for the structural parameter. Indeed, under i.i.d. sampling, least squares is consistent for the projection coefficient.

\[ \widehat{\beta} \underset{p}{\longrightarrow}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y]=\beta^{*} \neq \beta . \]

The inconsistency of least squares is typically referred to as endogeneity bias or estimation bias due to endogeneity. This is an imperfect label as the actual issue is inconsistency, not bias.

As the structural parameter \(\beta\) is the parameter of interest, endogeneity requires the development of alternative estimation methods. We discuss those in later sections.

12.3 Examples

The concept of endogeneity may be easiest to understand by example. We discuss three. In each case it is important to see how the structural parameter \(\beta\) is defined independently from the linear projection model.

Example: Measurement error in the regressor. Suppose that \((Y, Z)\) are joint random variables, \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid Z]=Z^{\prime} \beta\) is linear, and \(\beta\) is the structural parameter. \(Z\) is not observed. Instead we observe \(X=Z+u\) where \(u\) is a \(k \times 1\) measurement error, independent of \(e\) and \(Z\). This is an example of a latent variable model, where “latent” refers to an unobserved structural variable.

The model \(X=Z+u\) with \(Z\) and \(u\) independent and \(\mathbb{E}[u]=0\) is known as classical measurement error. This means that \(X\) is a noisy but unbiased measure of \(Z\).

By substitution we can express \(Y\) as a function of the observed variable \(X\).

\[ Y=Z^{\prime} \beta+e=(X-u)^{\prime} \beta+e=X^{\prime} \beta+v \]

where \(v=e-u^{\prime} \beta\). This means that \((Y, X)\) satisfy the linear equation

\[ Y=X^{\prime} \beta+v \]

with an error \(v\). But this error is not a projection error. Indeed,

\[ \mathbb{E}[X v]=\mathbb{E}\left[(Z+u)\left(e-u^{\prime} \beta\right)\right]=-\mathbb{E}\left[u u^{\prime}\right] \beta \neq 0 \]

if \(\beta \neq 0\) and \(\mathbb{E}\left[u u^{\prime}\right] \neq 0\). As we learned in the previous section, if \(\mathbb{E}[X \nu] \neq 0\) then least squares estimation will be inconsistent.

We can calculate the form of the projection coefficient (which is consistently estimated by least squares). For simplicity suppose that \(k=1\). We find

\[ \beta^{*}=\beta+\frac{\mathbb{E}[X \nu]}{\mathbb{E}\left[X^{2}\right]}=\beta\left(1-\frac{\mathbb{E}\left[u^{2}\right]}{\mathbb{E}\left[X^{2}\right]}\right) . \]

Since \(\mathbb{E}\left[u^{2}\right] / \mathbb{E}\left[X^{2}\right]<1\) the projection coefficient shrinks the structural parameter \(\beta\) towards zero. This is called measurement error bias or attenuation bias.

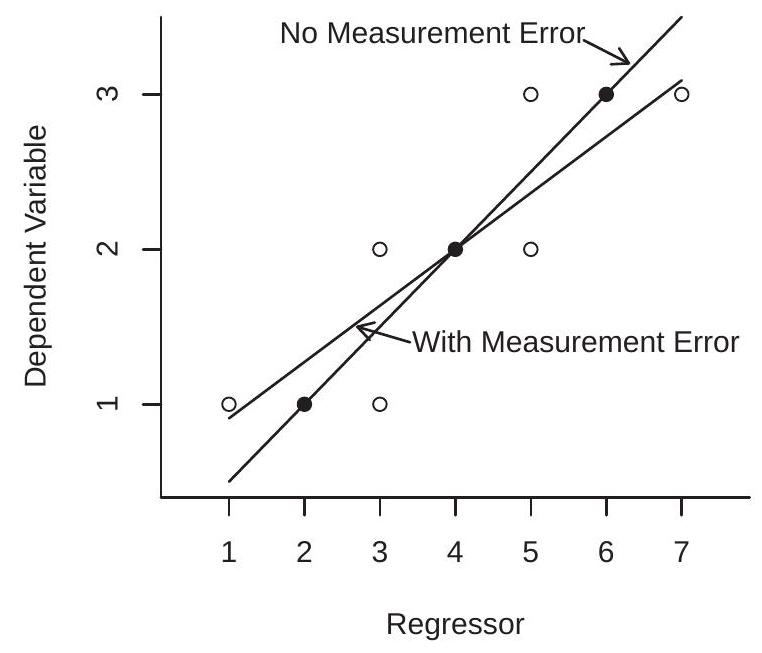

To illustrate, Figure 12.1(a) displays the impact of measurement error on the regression line. The three solid points are pairs \((Y, Z)\) which are measured without error. The regression function drawn through these three points is marked as “No Measurement Error”. The six open circles mark pairs \((Y, X)\) where \(X=Z+u\) with \(u=\{+1,-1\}\). Thus \(X\) is a mis-measured version of \(Z\). The six open circles spread the joint distribution along the \(\mathrm{x}\)-axis, but not along the \(\mathrm{y}\)-axis. The regression line drawn for these six points is marked as “With Measurement Error”. You can see that the latter regression line is flattened relative to the original regression function. This is the attenuation bias due to measurement error.

- Measurement Error

.jpg)

- Supply and Demand

Figure 12.1: Examples of Endogeneity

Example: Supply and Demand. The variables \(Q\) and \(P\) (quantity and price) are determined jointly by the demand equation

\[ Q=-\beta_{1} P+e_{1} \]

and the supply equation

\[ Q=\beta_{2} P+e_{2} \text {. } \]

Assume that \(e=\left(e_{1}, e_{2}\right)\) satisfies \(\mathbb{E}[e]=0\) and \(\mathbb{E}\left[e e^{\prime}\right]=\boldsymbol{I}_{2}\) (the latter for simplicity). The question is: if we regress \(Q\) on \(P\), what happens?

It is helpful to solve for \(Q\) and \(P\) in terms of the errors. In matrix notation,

\[ \left[\begin{array}{cc} 1 & \beta_{1} \\ 1 & -\beta_{2} \end{array}\right]\left(\begin{array}{l} Q \\ P \end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{l} e_{1} \\ e_{2} \end{array}\right) \]

so

\[ \begin{aligned} \left(\begin{array}{l} Q \\ P \end{array}\right) &=\left[\begin{array}{cc} 1 & \beta_{1} \\ 1 & -\beta_{2} \end{array}\right]^{-1}\left(\begin{array}{c} e_{1} \\ e_{2} \end{array}\right) \\ &=\left[\begin{array}{cc} \beta_{2} & \beta_{1} \\ 1 & -1 \end{array}\right]\left(\begin{array}{l} e_{1} \\ e_{2} \end{array}\right)\left(\frac{1}{\beta_{1}+\beta_{2}}\right) \\ &=\left(\begin{array}{c} \left(\beta_{2} e_{1}+\beta_{1} e_{2}\right) /\left(\beta_{1}+\beta_{2}\right) \\ \left(e_{1}-e_{2}\right) /\left(\beta_{1}+\beta_{2}\right) \end{array}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

The projection of \(Q\) on \(P\) yields \(Q=\beta^{*} P+e^{*}\) with \(\mathbb{E}\left[P e^{*}\right]=0\) and the projection coefficient is

\[ \beta^{*}=\frac{\mathbb{E}[P Q]}{\mathbb{E}\left[P^{2}\right]}=\frac{\beta_{2}-\beta_{1}}{2} . \]

The projection coefficient \(\beta^{*}\) equals neither the demand slope \(\beta_{1}\) nor the supply slope \(\beta_{2}\), but equals an average of the two. (The fact that it is a simple average is an artifact of the covariance structure.)

The OLS estimator satisfies \(\widehat{\beta} \underset{p}{\rightarrow} \beta^{*}\) and the limit does not equal either \(\beta_{1}\) or \(\beta_{2}\). This is called simultaneous equations bias. This occurs generally when \(Y\) and \(X\) are jointly determined, as in a market equilibrium.

Generally, when both the dependent variable and a regressor are simultaneously determined then the regressor should be treated as endogenous.

To illustrate, Figure 12.1(b) draws a supply/demand model with Quantity on the y-axis and Price on the \(\mathrm{x}\)-axis. The supply and demand equations are \(Q=P+\varepsilon_{1}\) and \(Q=4-P-\varepsilon_{2}\), respectively. Suppose that the errors each have the Rademacher distribution \(\varepsilon \in\{-1,+1\}\). This model has four equilibrium outcomes, marked by the four points in the figure. The regression line through these four points has a slope of zero and is marked as “Regression”. This is what would be measured by a least squares regression of observed quantity on observed price. This is endogeneity bias due to simultaneity.

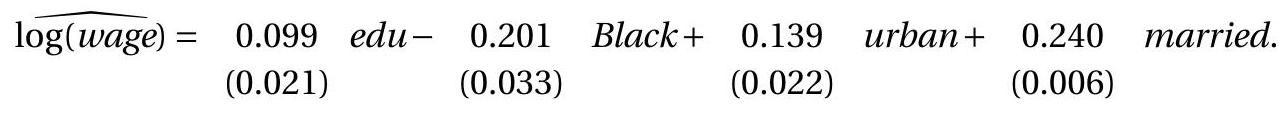

Example: Choice Variables as Regressors. Take the classic wage equation

\[ \log (\text { wage })=\beta \text { education }+e \]

with \(\beta\) the average causal effect of education on wages. If wages are affected by unobserved ability, and individuals with high ability self-select into higher education, then \(e\) contains unobserved ability, so education and \(e\) will be positively correlated. Hence education is endogenous. The positive correlation means that the linear projection coefficient \(\beta^{*}\) will be upward biased relative to the structural coefficient \(\beta\). Thus least squares (which is estimating the projection coefficient) will tend to over-estimate the causal effect of education on wages.

This type of endogeneity occurs generally when \(Y\) and \(X\) are both choices made by an economic agent, even if they are made at different points in time.

Generally, when both the dependent variable and a regressor are choice variables made by the same agent, the variables should be treated as endogenous.

This example was illustrated back in Figure \(2.8\) which displayed the joint distribution of wages and education of the population of Jennifers and Georges. In Figure 2.8, the plotted Average Causal Effect is the structural impact (on average in the population) of college education on wages. The plotted regression line has a larger slope, as it adds the endogeneity bias due to the fact that education is a choice variable.

12.4 Endogenous Regressors

We have defined endogeneity as the context where a regressor is correlated with the equation error. The converse of endogeneity is exogeneity. That is, we say a regressor \(X\) is exogenous for \(\beta\) if \(\mathbb{E}[X e]=\) 0 . In general the distinction in an economic model is that a regressor \(X\) is endogenous if it is jointly determined with \(Y\), while a regressor \(X\) is exogenous if it is determined separately from \(Y\).

In most applications only a subset of the regressors are treated as endogenous. Partition \(X=\left(X_{1}, X_{2}\right)\) with dimensions \(\left(k_{1}, k_{2}\right)\) so that \(X_{1}\) contains the exogenous regressors and \(X_{2}\) contains the endogenous regressors. As the dependent variable \(Y\) is also endogenous, we sometimes differentiate \(X_{2}\) by calling it the endogenous right-hand-side variable. Similarly partition \(\beta=\left(\beta_{1}, \beta_{2}\right)\). With this notation the structural equation is

\[ Y=X_{1}^{\prime} \beta_{1}+X_{2}^{\prime} \beta_{2}+e . \]

An alternative notation is as follows. Let \(Y_{2}=X_{2}\) be the endogenous regressors and rename the dependent variable \(Y\) as \(Y_{1}\). Then the structural equation is

\[ Y_{1}=X_{1}^{\prime} \beta_{1}+Y_{2}^{\prime} \beta_{2}+e . \]

This is especially useful so that the notation clarifies which variables are endogenous and which exogenous. We also write \(\vec{Y}=\left(Y_{1}, Y_{2}\right)\) as the set of endogenous variables. We use the notation \(\vec{Y}\) so that there is no confusion with \(Y\) as defined in (12.3).

The assumptions regarding the regressors and regression error are

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathbb{E}\left[X_{1} e\right]=0 \\ &\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{2} e\right] \neq 0 . \end{aligned} \]

The endogenous regressors \(Y_{2}\) are the critical variables discussed in the examples of the previous section - simultaneous variables, choice variables, mis-measured regressors - that are potentially correlated with the equation error \(e\). In many applications \(k_{2}\) is small (1 or 2 ). The exogenous variables \(X_{1}\) are the remaining regressors (including the equation intercept) and can be low or high dimensional.

12.5 Instruments

To consistently estimate \(\beta\) we require additional information. One type of information which is commonly used in economic applications are what we call instruments.

Definition \(12.1\) The \(\ell \times 1\) random vector \(Z\) is an instrumental variable for (12.3) if

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[Z e] &=0 \\ \mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right] &>0 \\ \operatorname{rank}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right]\right) &=k . \end{aligned} \]

There are three components to the definition as given. The first (12.5) is that the instruments are uncorrelated with the regression error. The second (12.6) is a normalization which excludes linearly redundant instruments. The third (12.7) is often called the relevance condition and is essential for the identification of the model, as we discuss later. A necessary condition for (12.7) is that \(\ell \geq k\).

Condition (12.5) - that the instruments are uncorrelated with the equation error - is often described as that they are exogenous in the sense that they are determined outside the model for \(Y\).

Notice that the regressors \(X_{1}\) satisfy condition (12.5) and thus should be included as instrumental variables. They are therefore a subset of the variables \(Z\). Notationally we make the partition

\[ Z=\left(\begin{array}{l} Z_{1} \\ Z_{2} \end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{c} X_{1} \\ Z_{2} \end{array}\right) \begin{aligned} &k_{1} \\ &\ell_{2} \end{aligned} . \]

Here, \(X_{1}=Z_{1}\) are the included exogenous variables and \(Z_{2}\) are the excluded exogenous variables. That is, \(Z_{2}\) are variables which could be included in the equation for \(Y\) (in the sense that they are uncorrelated with \(e\) ) yet can be excluded as they have true zero coefficients in the equation. With this notation we can also write the structural equation (12.4) as

\[ Y_{1}=Z_{1}^{\prime} \beta_{1}+Y_{2}^{\prime} \beta_{2}+e . \]

This is useful notation as it clarifies that the variable \(Z_{1}\) is exogenous and the variable \(Y_{2}\) is endogenous.

Many authors describe \(Z_{1}\) as the “exogenous variables”, \(Y_{2}\) as the “endogenous variables”, and \(Z_{2}\) as the “instrumental variables”.

We say that the model is just-identified if \(\ell=k\) and over-identified if \(\ell>k\).

What variables can be used as instrumental variables? From the definition \(\mathbb{E}[Z e]=0\) the instrument must be uncorrelated with the equation error, meaning that it is excluded from the structural equation as mentioned above. From the rank condition (12.7) it is also important that the instrumental variables be correlated with the endogenous variables \(Y_{2}\) after controlling for the other exogenous variables \(Z_{1}\). These two requirements are typically interpreted as requiring that the instruments be determined outside the system for \(\vec{Y}\), causally determine \(Y_{2}\), but do not causally determine \(Y_{1}\) except through \(Y_{2}\).

Let’s take the three examples given above.

Measurement error in the regressor. When \(X\) is a mis-measured version of \(Z\) a common choice for an instrument \(Z_{2}\) is an alternative measurement of \(Z\). For this \(Z_{2}\) to satisfy the property of an instrumental variable the measurement error in \(Z_{2}\) must be independent of that in \(X\).

Supply and Demand. An appropriate instrument for price \(P\) in a demand equation is a variable \(Z_{2}\) which influences supply but not demand. Such a variable affects the equilibrium values of \(P\) and \(Q\) but does not directly affect price except through quantity. Variables which affect supply but not demand are typically related to production costs.

An appropriate instrument for price in a supply equation is a variable which influences demand but not supply. Such a variable affects the equilibrium values of price and quantity but only affects price through quantity.

Choice Variable as Regressor. An ideal instrument affects the choice of the regressor (education) but does not directly influence the dependent variable (wages) except through the indirect effect on the regressor. We will discuss an example in the next section.

12.6 Example: College Proximity

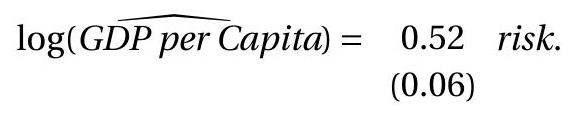

In a influential paper David Card (1995) suggested if a potential student lives close to a college this reduces the cost of attendence and thereby raises the likelihood that the student will attend college. However, college proximity does not directly affect a student’s skills or abilities so should not have a direct effect on his or her market wage. These considerations suggest that college proximity can be used as an instrument for education in a wage regression. We use the simplest model reported in Card’s paper to illustrate the concepts of instrumental variables throughout the chapter.

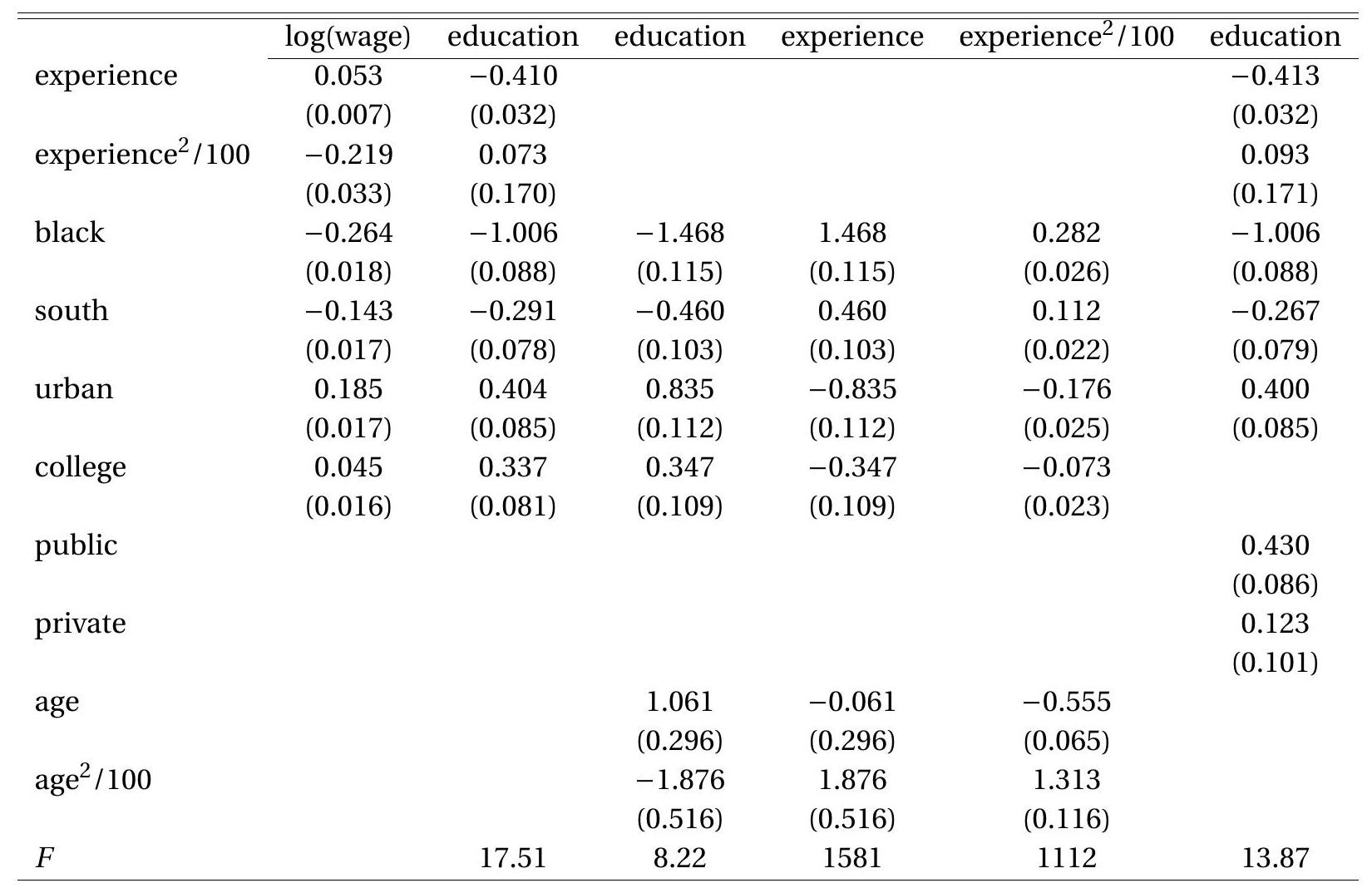

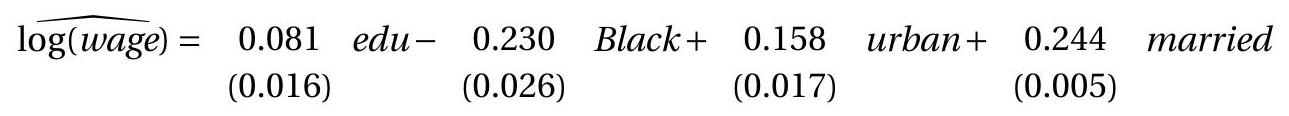

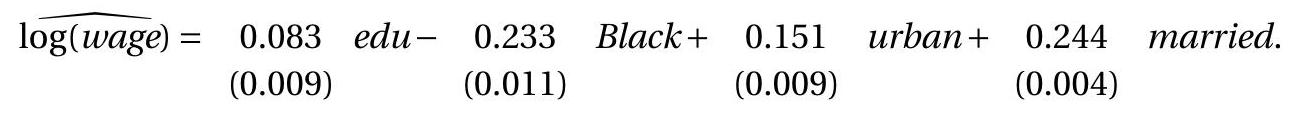

Card used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Young Men (NLSYM) for 1976. A baseline least squares wage regression for his data set is reported in the first column of Table 12.1. The dependent variable is the log of weekly earnings. The regressors are education (years of schooling), experience (years of work experience, calculated as age (years) less education \(+6\) ), experience \({ }^{2} / 100\), Black, south (an indicator for residence in the southern region of the U.S.), and urban (an indicator for residence in a standard metropolitan statistical area). We drop observations for which wage is missing. The remaining sample has 3,010 observations. His data is the file Card1995 on the textbook website. The point estimate obtained by least squares suggests an \(7 %\) increase in earnings for each year of education.

Table 12.1: Instrumental Variable Wage Regressions

| education | OLS | IV(a) | IV(b) | 2SLS(a) | 2SLS(b) | LIML |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(0.074\) | \(0.132\) | \(0.133\) | \(0.161\) | \(0.160\) | \(0.164\) | |

| \((0.004)\) | \((0.049)\) | \((0.051)\) | \((0.040)\) | \((0.041)\) | \((0.042)\) | |

| \(0.084\) | \(0.107\) | \(0.056\) | \(0.119\) | \(0.047\) | \(0.120\) | |

| experience \(2 / 100\) | \(-0.224\) | \(-0.228\) | \(-0.080\) | \(-0.231\) | \(-0.032\) | \(-0.231\) |

| \((0.032)\) | \((0.035)\) | \((0.133)\) | \((0.037)\) | \((0.127)\) | \((0.037)\) | |

| Black | \(-0.190\) | \(-0.131\) | \(-0.103\) | \(-0.102\) | \(-0.064\) | \(-0.099\) |

| \((0.017)\) | \((0.051)\) | \((0.075)\) | \((0.044)\) | \((0.061)\) | \((0.045)\) | |

| south | \(-0.125\) | \(-0.105\) | \(-0.098\) | \(-0.095\) | \(-0.086\) | \(-0.094\) |

| \((0.015)\) | \((0.023)\) | \((0.0284)\) | \((0.022)\) | \((0.026)\) | \((0.022)\) | |

| urban | \(0.161\) | \(0.131\) | \(0.108\) | \(0.116\) | \(0.083\) | \(0.115\) |

| \((0.015)\) | \((0.030)\) | \((0.049)\) | \((0.026)\) | \((0.041)\) | \((0.027)\) | |

| Sargan | \(0.82\) | \(0.52\) | \(0.82\) | |||

| p-value | \(0.37\) | \(0.47\) | \(0.37\) |

Notes:

IV(a) uses college as an instrument for education.

IV(b) uses college, age, and age \(^{2} / 100\) as instruments for education, experience, and experience \({ }^{2} / 100\).

2SLS(a) uses public and private as instruments for education.

\(2 \mathrm{SLS}(\mathrm{b})\) uses public, private, age, and age \({ }^{2}\) as instruments for education, experience, and experience \(^{2} / 100\).

LIML uses public and private as instruments for education.

As discussed in the previous sections it is reasonable to view years of education as a choice made by an individual and thus is likely endogenous for the structural return to education. This means that least squares is an estimate of a linear projection but is inconsistent for coefficient of a structural equation representing the causal impact of years of education on expected wages. Labor economics predicts that ability, education, and wages will be positively correlated. This suggests that the population projection coefficient estimated by least squares will be higher than the structural parameter (and hence upwards biased). However, the sign of the bias is uncertain because there are multiple regressors and there are other potential sources of endogeneity.

To instrument for the endogeneity of education, Card suggested that a reasonable instrument is a dummy variable indicating if the individual grew up near a college. We will consider three measures:

college Grew up in same county as a 4-year college

public Grew up in same county as a 4-year public college

private Grew up in same county as a 4-year private college.

12.7 Reduced Form

The reduced form is the relationship between the endogenous regressors \(Y_{2}\) and the instruments \(Z\). A linear reduced form model for \(Y_{2}\) is

\[ Y_{2}=\Gamma^{\prime} Z+u_{2}=\Gamma_{12}^{\prime} Z_{1}+\Gamma_{22}^{\prime} Z_{2}+u_{2} \]

This is a multivariate regression as introduced in Chapter 11 . The \(\ell \times k_{2}\) coefficient matrix \(\Gamma\) is defined by linear projection:

\[ \Gamma=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[Z Y_{2}^{\prime}\right] \]

This implies \(\mathbb{E}\left[Z u_{2}^{\prime}\right]=0\). The projection coefficient (12.11) is well defined and unique under (12.6).

We also construct the reduced form for \(Y_{1}\). Substitute (12.10) into (12.9) to obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} Y_{1} &=Z_{1}^{\prime} \beta_{1}+\left(\Gamma_{12}^{\prime} Z_{1}+\Gamma_{22}^{\prime} Z_{2}+u_{2}\right)^{\prime} \beta_{2}+e \\ &=Z_{1}^{\prime} \lambda_{1}+Z_{2}^{\prime} \lambda_{2}+u_{1} \\ &=Z^{\prime} \lambda+u_{1} \end{aligned} \]

where

\[ \begin{aligned} &\lambda_{1}=\beta_{1}+\Gamma_{12} \beta_{2} \\ &\lambda_{2}=\Gamma_{22} \beta_{2} \\ &u_{1}=u_{2}^{\prime} \beta_{2}+e . \end{aligned} \]

We can also write

\[ \lambda=\bar{\Gamma} \beta \]

where

\[ \bar{\Gamma}=\left[\begin{array}{cc} \boldsymbol{I}_{k_{1}} & \Gamma_{12} \\ 0 & \Gamma_{22} \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc} \boldsymbol{I}_{k_{1}} & \Gamma \\ 0 & \end{array}\right] . \]

Together, the reduced form equations for the system are

\[ \begin{aligned} &Y_{1}=\lambda^{\prime} Z+u_{1} \\ &Y_{2}=\Gamma^{\prime} Z+u_{2} . \end{aligned} \]

or

\[ \vec{Y}=\left[\begin{array}{cc} \lambda_{1}^{\prime} & \lambda_{2}^{\prime} \\ \Gamma_{12}^{\prime} & \Gamma_{22}^{\prime} \end{array}\right] Z+u \]

where \(u=\left(u_{1}, u_{2}\right)\).

The relationships (12.14)-(12.16) are critically important for understanding the identification of the structural parameters \(\beta_{1}\) and \(\beta_{2}\), as we discuss below. These equations show the tight relationship between the structural parameters \(\left(\beta_{1}\right.\) and \(\left.\beta_{2}\right)\) and the reduced form parameters \((\Gamma\) and \(\lambda)\).

The reduced form equations are projections so the coefficients may be estimated by least squares (see Chapter 11). The least squares estimators of (12.11) and (12.13) are

\[ \begin{aligned} &\widehat{\Gamma}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} Z_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} Y_{2 i}^{\prime}\right) \\ &\widehat{\lambda}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} Z_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} Y_{1 i}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

12.8 Identification

A parameter is identified if it is a unique function of the probability distribution of the observables. One way to show that a parameter is identified is to write it as an explicit function of population moments. For example, the reduced form coefficient matrices \(\Gamma\) and \(\lambda\) are identified because they can be written as explicit functions of the moments of the variables \((Y, X, Z)\). That is,

\[ \begin{aligned} &\Gamma=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[Z Y_{2}^{\prime}\right] \\ &\lambda=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[Z Y_{1}\right] . \end{aligned} \]

These are uniquely determined by the probability distribution of \(\left(Y_{1}, Y_{2}, Z\right)\) if Definition \(12.1\) holds, because this includes the requirement that \(\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]\) is invertible.

We are interested in the structural parameter \(\beta\). It relates to \((\lambda, \Gamma)\) through (12.16). \(\beta\) is identified if it uniquely determined by this relation. This is a set of \(\ell\) equations with \(k\) unknowns with \(\ell \geq k\). From linear algebra we know that there is a unique solution if and only if \(\bar{\Gamma}\) has full rank \(k\).

\[ \operatorname{rank}(\bar{\Gamma})=k . \]

Under (12.22) \(\beta\) can be uniquely solved from (12.16). If (12.22) fails then (12.16) has fewer equations than coefficients so there is not a unique solution.

We can write \(\bar{\Gamma}=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right]\). Combining this with (12.16) we obtain

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[Z Y_{1}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right] \beta \]

or

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Z Y_{1}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right] \beta \]

which is a set of \(\ell\) equations with \(k\) unknowns. This has a unique solution if (and only if)

\[ \operatorname{rank}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right]\right)=k \]

which was listed in (12.7) as a condition of Definition 12.1. (Indeed, this is why it was listed as part of the definition.) We can also see that (12.22) and (12.23) are equivalent ways of expressing the same requirement. If this condition fails then \(\beta\) will not be identified. The condition (12.22)-(12.23) is called the relevance condition.

It is useful to have explicit expressions for the solution \(\beta\). The easiest case is when \(\ell=k\). Then (12.22) implies \(\bar{\Gamma}\) is invertible so the structural parameter equals \(\beta=\bar{\Gamma}^{-1} \lambda\). It is a unique solution because \(\bar{\Gamma}\) and \(\lambda\) are unique and \(\bar{\Gamma}\) is invertible.

When \(\ell>k\) we can solve for \(\beta\) by applying least squares to the system of equations \(\lambda=\bar{\Gamma} \beta\). This is \(\ell\) equations with \(k\) unknowns and no error. The least squares solution is \(\beta=\left(\bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} \bar{\Gamma}\right)^{-1} \bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} \lambda\). Under (12.22) the matrix \(\bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} \bar{\Gamma}\) is invertible so the solution is unique.

\(\beta\) is identified if \(\operatorname{rank}(\bar{\Gamma})=k\), which is true if and only if \(\operatorname{rank}\left(\Gamma_{22}\right)=k_{2}\) (by the upper-diagonal structure of \(\bar{\Gamma})\). Thus the key to identification of the model rests on the \(\ell_{2} \times k_{2}\) matrix \(\Gamma_{22}\) in (12.10). To see this, recall the reduced form relationships (12.14)-(12.15). We can see that \(\beta_{2}\) is identified from (12.15) alone, and the necessary and sufficient condition is \(\operatorname{rank}\left(\Gamma_{22}\right)=k_{2}\). If this is satisfied then the solution equals \(\beta_{2}=\left(\Gamma_{22}^{\prime} \Gamma_{22}\right)^{-1} \Gamma_{22}^{\prime} \lambda_{2} \cdot \beta_{1}\) is identified from this and (12.14), with the explicit solution \(\beta_{1}=\lambda_{1}-\Gamma_{12}\left(\Gamma_{22}^{\prime} \Gamma_{22}\right)^{-1} \Gamma_{22}^{\prime} \lambda_{2}\). In the just-identified case \(\left(\ell_{2}=k_{2}\right)\) these equations simplify as \(\beta_{2}=\Gamma_{22}^{-1} \lambda_{2}\) and \(\beta_{1}=\lambda_{1}-\Gamma_{12} \Gamma_{22}^{-1} \lambda_{2}\)

12.9 Instrumental Variables Estimator

In this section we consider the special case where the model is just-identified so that \(\ell=k\).

The assumption that \(Z\) is an instrumental variable implies that \(\mathbb{E}[Z e]=0\). Making the substitution \(e=Y_{1}-X^{\prime} \beta\) we find \(\mathbb{E}\left[Z\left(Y_{1}-X^{\prime} \beta\right)\right]=0\). Expanding,

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Z Y_{1}\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right] \beta=0 . \]

This is a system of \(\ell=k\) equations and \(k\) unknowns. Solving for \(\beta\) we find

\[ \beta=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[Z Y_{1}\right] . \]

This requires that the matrix \(\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right]\) is invertible, which holds under (12.7) or equivalently (12.23).

The instrumental variables (IV) estimator \(\beta\) replaces population by sample moments. We find

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}} &=\left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} Y_{1 i}\right) \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} Y_{1 i}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

More generally, given any variable \(W \in \mathbb{R}^{k}\) it is common to refer to the estimator

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} W_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} W_{i} Y_{1 i}\right) \]

as the IV estimator for \(\beta\) using the instrument \(W\).

Alternatively, recall that when \(\ell=k\) the structural parameter can be written as a function of the reduced form parameters as \(\beta=\bar{\Gamma}^{-1} \lambda\). Replacing \(\bar{\Gamma}\) and \(\lambda\) by their least squares estimators (12.18)-(12.19) we can construct what is called the Indirect Least Squares (ILS) estimator. Using the matrix algebra representations

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{ils}} &=\widehat{\bar{\Gamma}}^{-1} \widehat{\lambda} \\ &=\left(\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\right)^{-1}\left(\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right)\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

We see that this equals the IV estimator (12.24). Thus the ILS and IV estimators are identical.

Given the IV estimator we define the residual \(\widehat{e}_{i}=Y_{1 i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}\). It satisfies

\[ \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \widehat{\boldsymbol{e}}=\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right)=0 \]

Since \(Z\) includes an intercept this means that the residuals sum to zero and are uncorrelated with the included and excluded instruments.

To illustrate IV regression we estimate the reduced form equations, treating education as endogenous and using college as an instrumental variable. The reduced form equations for log(wage) and education are reported in the first and second columns of Table 12.2. Table 12.2: Reduced Form Regressions

Of particular interest is the equation for the endogenous regressor education, and the coefficients for the excluded instruments - in this case college. The estimated coefficient equals \(0.337\) with a small standard error. This implies that growing up near a 4-year college increases average educational attainment by \(0.3\) years. This seems to be a reasonable magnitude.

Since the structural equation is just-identified with one right-hand-side endogenous variable the ILS/IV estimate for the education coefficient is the ratio of the coefficient estimates for the instrument college in the two equations, e.g. \(0.045 / 0.337=0.13\), implying a \(13 %\) return to each year of education. This is substantially greater than the \(7 %\) least squares estimate from the first column of Table 12.1. The IV estimates of the full equation are reported in the second column of Table 12.1. One first reaction is surprise that the IV estimate is larger than the OLS estimate. The endogeneity of educational choice should lead to upward bias in the OLS estimator, which predicts that the IV estimate should have been smaller than the OLS estimator. An alternative explanation may be needed. One possibility is heterogeneous education effects (when the education coefficient \(\beta\) is heterogenous across individuals). In Section \(12.34\) we show that in this context the IV estimator picks up this treatment effect for a subset of the population, and this may explain why IV estimation results in a larger estimated coefficient.

Card (1995) also points out that if education is endogenous then so is our measure of experience as it is calculated by subtracting education from age. He suggests that we can use the variables age and age \({ }^{2}\) as instruments for experience and experience \({ }^{2}\). The age variables are exogenous (not choice variables) yet highly correlated with experience and experience \({ }^{2}\). Notice that this approach treats experience \({ }^{2}\) as a variable separate from experience. Indeed, this is the correct approach.

Following this recommendation we now have three endogenous regressors and three instruments. We present the three reduced form equations for the three endogenous regressors in the third through fifth columns of Table 12.2. It is interesting to compare the equations for education and experience. The two sets of coefficients are simply the sign change of the other with the exception of the coefficient on age. Indeed this must be the case because the three variables are linearly related. Does this cause a problem for 2SLS? Fortunately, no. The fact that the coefficient on age is not simply a sign change means that the equations are not linearly singular. Hence Assumption (12.22) is not violated.

The IV estimates using the three instruments college, age, and age \({ }^{2}\) for the endogenous regressors education, experience, and experience \({ }^{2}\) is presented in the third column of Table 12.1. The estimate of the returns to schooling is not affected by this change in the instrument set, but the estimated return to experience profile flattens (the quadratic effect diminishes).

The IV estimator may be calculated in Stata using the ivregress 2 sls command.

12.10 Demeaned Representation

Does the well-known demeaned representation for linear regression (3.18) carry over to the IV estimator? To see, write the linear projection equation in the format \(Y_{1}=X^{\prime} \beta+\alpha+e\) where \(\alpha\) is the intercept and \(X\) does not contain a constant. Similarly, partition the instrument as \((1, Z)\) where \(Z\) does not contain a constant. We can write the IV estimator for the \(i^{t h}\) equation as

\[ Y_{1 i}=X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}+\widehat{\alpha}_{\mathrm{iv}}+\widehat{e}_{i} . \]

The orthogonality (12.25) implies the two-equation system

\[ \begin{aligned} &\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{1 i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}-\widehat{\alpha}_{\mathrm{iv}}\right)=0 \\ &\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}\left(Y_{1 i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}-\widehat{\alpha}_{\mathrm{iv}}\right)=0 . \end{aligned} \]

The first equation implies \(\widehat{\alpha}_{\mathrm{iv}}=\overline{Y_{1}}-\bar{X}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}\). Substituting into the second equation

\[ \sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}\left(\left(Y_{1 i}-\overline{Y_{1}}\right)-\left(X_{i}-\bar{X}\right)^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}\right) \]

and solving for \(\widehat{\beta}_{\text {iv }}\) we find

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}} &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}\left(X_{i}-\bar{X}\right)^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}\left(Y_{1 i}-\bar{Y}_{1}\right)\right) \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Z_{i}-\bar{Z}\right)\left(X_{i}-\bar{X}\right)^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Z_{i}-\bar{Z}\right)\left(Y_{1 i}-\bar{Y}_{1}\right)\right) . \end{aligned} \]

Thus the demeaning equations for least squares carry over to the IV estimator. The coefficient estimator \(\widehat{\beta}_{\text {iv }}\) is a function only of the demeaned data.

12.11 Wald Estimator

In many cases including the Card proximity example the excluded instrument is a binary (dummy) variable. Let’s focus on that case and suppose that the model has just one endogenous regressor and no other regressors beyond the intercept. The model can be written as \(Y=X \beta+\alpha+e\) with \(\mathbb{E}[e \mid Z]=0\) and \(Z\) binary. Take expectations of the structural equation given \(Z=1\) and \(Z=0\), respectively. We obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathbb{E}[Y \mid Z=1]=\mathbb{E}[X \mid Z=1] \beta+\alpha \\ &\mathbb{E}[Y \mid Z=0]=\mathbb{E}[X \mid Z=0] \beta+\alpha . \end{aligned} \]

Subtracting and dividing we obtain an expression for the slope coefficient

\[ \beta=\frac{\mathbb{E}[Y \mid Z=1]-\mathbb{E}[Y \mid Z=0]}{\mathbb{E}[X \mid Z=1]-\mathbb{E}[X \mid Z=0]} . \]

The natural moment estimator replaces the expectations by the averages within the “grouped data” where \(Z_{i}=1\) and \(Z_{i}=0\), respectively. That is, define the group means

\[ \begin{array}{ll} \bar{Y}_{1}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} Y_{i}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}}, & \bar{Y}_{0}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-Z_{i}\right) Y_{i}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-Z_{i}\right)} \\ \bar{X}_{1}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} X_{i}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}}, & \bar{X}_{0}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-Z_{i}\right) X_{i}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-Z_{i}\right)} \end{array} \]

and the moment estimator

\[ \widehat{\beta}=\frac{\bar{Y}_{1}-\bar{Y}_{0}}{\bar{X}_{1}-\bar{X}_{0}} . \]

This is the “Wald estimator” of Wald (1940).

These expressions are rather insightful. (12.27) shows that the structural slope coefficient is the expected change in \(Y\) due to changing the instrument divided by the expected change in \(X\) due to changing the instrument. Informally, it is the change in \(Y\) (due to \(Z\) ) over the change in \(X\) (due to \(Z\) ). Equation (12.28) shows that the slope coefficient can be estimated by the ratio of differences in means.

The expression (12.28) may appear like a distinct estimator from the IV estimator \(\widehat{\beta}_{\text {iv }}\) but it turns out that they are the same. That is, \(\widehat{\beta}=\widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}\). To see this, use (12.26) to find

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}\left(Y_{i}-\bar{Y}\right)}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i}\left(X_{i}-\bar{X}\right)}=\frac{\bar{Y}_{1}-\bar{Y}}{\bar{X}_{1}-\bar{X}} . \]

Then notice

\[ \bar{Y}_{1}-\bar{Y}=\bar{Y}_{1}-\left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} Z_{i} \bar{Y}_{1}+\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-Z_{i}\right) \bar{Y}_{0}\right)=(1-\bar{Z})\left(\bar{Y}_{1}-\bar{Y}_{0}\right) \]

and similarly

\[ \bar{X}_{1}-\bar{X}=(1-\bar{Z})\left(\bar{X}_{1}-\bar{X}_{0}\right) \]

and hence

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}}=\frac{(1-\bar{Z})\left(\bar{Y}_{1}-\bar{Y}_{0}\right)}{(1-\bar{Z})\left(\bar{X}_{1}-\bar{X}_{0}\right)}=\widehat{\beta} \]

as defined in (12.28). Thus the Wald estimator equals the IV estimator.

We can illustrate using the Card proximity example. If we estimate a simple IV model with no covariates we obtain the estimate \(\widehat{\beta}_{\text {iv }}=0.19\). If we estimate the group-mean of log wages and education based on the instrument college we find

| near college | not near college | difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\log (\) wage) | \(6.311\) | \(6.156\) | \(0.155\) |

| education | \(13.527\) | \(12.698\) | \(0.829\) |

| ratio | \(0.19\) |

Based on these estimates the Wald estimator of the slope coefficient is \((6.311-6.156) /(13.527-12.698)=\) \(0.155 / 0.829=0.19\), the same as the IV estimator.

12.12 Two-Stage Least Squares

The IV estimator described in the previous section presumed \(\ell=k\). Now we allow the general case of \(\ell \geq k\). Examining the reduced-form equation (12.13) we see

\[ \begin{aligned} Y_{1} &=Z^{\prime} \bar{\Gamma} \beta+u_{1} \\ \mathbb{E}\left[Z u_{1}\right] &=0 . \end{aligned} \]

Defining \(W=\bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} Z\) we can write this as

\[ \begin{aligned} Y_{1} &=W^{\prime} \beta+u_{1} \\ \mathbb{E}\left[W u_{1}\right] &=0 . \end{aligned} \]

One way of thinking about this is that \(Z\) is set of candidate instruments. The instrument vector \(W=\bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} Z\) is a \(k\)-dimentional set of linear combinations.

Suppose that \(\bar{\Gamma}\) were known. Then we would estimate \(\beta\) by least squares of \(Y_{1}\) on \(W=\bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} Z\)

\[ \widehat{\beta}=\left(\boldsymbol{W}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{W}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{W}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}\right)=\left(\bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z} \bar{\Gamma}\right)^{-1}\left(\bar{\Gamma}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) . \]

While this is infeasible we can estimate \(\bar{\Gamma}\) from the reduced form regression. Replacing \(\bar{\Gamma}\) with its estimator \(\widehat{\Gamma}=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\) we obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }} &=\left(\widehat{\Gamma}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z} \widehat{\Gamma}\right)^{-1}\left(\widehat{\Gamma}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-\mathbf{1}} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \end{aligned} \]

This is called the two-stage-least squares (2SLS) estimator. It was originally proposed by Theil (1953) and Basmann (1957) and is a standard estimator for linear equations with instruments.

If the model is just-identified, so that \(k=\ell\), then 2SLS simplifies to the IV estimator of the previous section. Since the matrices \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\) and \(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\) are square we can factor

\[ \begin{aligned} \left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \end{aligned} \]

(Once again, this only works when \(k=\ell\).) Then

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }} &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}=\widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{iv}} \end{aligned} \]

as claimed. This shows that the 2SLS estimator as defined in (12.29) is a generalization of the IV estimator defined in (12.24).

There are several alternative representations of the 2SLS estimator which we now describe. First, defining the projection matrix

\[ \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}=\boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \]

we can write the 2SLS estimator more compactly as

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} . \]

This is useful for representation and derivations but is not useful for computation as the \(n \times n\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\) is too large to compute when \(n\) is large.

Second, define the fitted values for \(\boldsymbol{X}\) from the reduced form \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}=\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{X}=\boldsymbol{Z} \widehat{\Gamma}\). Then the 2SLS estimator can be written as

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }}=\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \]

This is an IV estimator as defined in the previous section using \(\widehat{X}\) as an instrument for \(X\).

Third, because \(\boldsymbol{P}_{Z}\) is idempotent we can also write the 2SLS estimator as

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}=\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}\right)^{-1} \widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \]

which is the least squares estimator obtained by regressing \(Y_{1}\) on the fitted values \(\widehat{X}\).

This is the source of the “two-stage” name as it can be computed as follows.

Regress \(X\) on \(Z\) to obtain the fitted \(\widehat{X}: \widehat{\Gamma}=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\) and \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}=\boldsymbol{Z} \widehat{\Gamma}=\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{X}\).

Regress \(Y_{1}\) on \(\widehat{X}: \widehat{\beta}_{2 s l s}=\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}\right)^{-1} \widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\)

It is useful to scrutinize the projection \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}\). Recall, \(\boldsymbol{X}=\left[\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}, \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}\right]\) and \(\boldsymbol{Z}=\left[\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}, \boldsymbol{Z}_{2}\right]\). Notice \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}_{1}=\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1}=\) \(Z_{1}\) because \(Z_{1}\) lies in the span of \(\boldsymbol{Z}\). Then \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}=\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}_{1}, \widehat{\boldsymbol{Y}}_{2}\right]=\left[\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}, \widehat{\boldsymbol{Y}}_{2}\right]\). This shows that in the second stage we regress \(Y_{1}\) on \(Z_{1}\) and \(\widehat{Y}_{2}\). This means that only the endogenous variables \(Y_{2}\) are replaced by their fitted values, \(\widehat{Y}_{2}=\widehat{\Gamma}_{12}^{\prime} Z_{1}+\widehat{\Gamma}_{22}^{\prime} Z_{2}\).

A fourth representation of 2SLS can be obtained using the FWL Theorem. The third representation and following discussion showed that 2SLS is obtained as least squares of \(Y_{1}\) on the fitted values \(\left(Z_{1}, \widehat{Y}_{2}\right)\). Hence the coefficient \(\widehat{\beta}_{2}\) on the endogenous variables can be found by residual regression. Set \(\boldsymbol{P}_{1}=\) \(Z_{1}\left(Z_{1}^{\prime} Z_{1}\right)^{-1} Z_{1}^{\prime}\). Applying the FWL theorem we obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{2} &=\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{Y}}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\right) \widehat{\boldsymbol{Y}}_{2}\right)^{-1}\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{Y}}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\right) \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) \end{aligned} \]

because \(\boldsymbol{P}_{Z} \boldsymbol{P}_{1}=\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\).

A fifth representation can be obtained by a further projection. The projection matrix \(\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\) can be replaced by the projection onto the pair \(\left[\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}, \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\right.\) ] where \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}=\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}\right) \boldsymbol{Z}_{2}\) is \(\boldsymbol{Z}_{2}\) projected orthogonal to \(\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}\). Since \(\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}\) and \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\) are orthogonal, \(\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}=\boldsymbol{P}_{1}+\boldsymbol{P}_{2}\) where \(\boldsymbol{P}_{2}=\widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\left(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\right)^{-1} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}^{\prime}\). Thus \(\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}-\boldsymbol{P}_{1}=\boldsymbol{P}_{2}\) and

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{2} &=\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{2} \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{P}_{2} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\left(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\right)^{-1} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\left(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}\right)^{-1} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Z}}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

Given the 2SLS estimator we define the residual \(\widehat{e}_{i}=Y_{1 i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{2 s l s}\). When the model is overidentified the instruments and residuals are not orthogonal. That is, \(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \widehat{\boldsymbol{e}} \neq 0\). It does, however, satisfy

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \widehat{\boldsymbol{e}} &=\widehat{\boldsymbol{\Gamma}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \widehat{\boldsymbol{e}} \\ &=\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \widehat{\boldsymbol{e}} \\ &=\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X} \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }}=0 . \end{aligned} \]

Returning to Card’s college proximity example suppose that we treat experience as exogeneous but that instead of using the single instrument college (grew up near a 4-year college) we use the two instruments (public, private) (grew up near a public/private 4-year college, respectively). In this case we have one endogenous variable (education) and two instruments (public, private). The estimated reduced form equation for education is presented in the sixth column of Table 12.2. In this specification the coefficient on public - growing up near a public 4-year college - is somewhat larger than that found for the variable college in the previous specification (column 2). Furthermore, the coefficient on private-growing up near a private 4-year college - is much smaller. This indicates that the key impact of proximity on education is via public colleges rather than private colleges.

The 2SLS estimates obtained using these two instruments are presented in the fourth column of Table 12.1. The coefficient on education increases to \(0.161\), indicating a \(16 %\) return to a year of education. This is roughly twice as large as the estimate obtained by least squares in the first column.

Additionally, if we follow Card and treat experience as endogenous and use age as an instrument we now have three endogenous variables (education, experience, experience \({ }^{2} / 100\) ) and four instruments (public, private, age, \(a g e^{2}\) ). We present the 2SLS estimates using this specification in the fifth column of Table 12.1. The estimate of the return to education remains \(16 %\) and the return to experience flattens.

You might wonder if we could use all three instruments - college, public, and private. The answer is no. This is because college \(=\) public \(+\) private so the three variables are colinear. Since the instruments are linearly related the three together would violate the full-rank condition (12.6).

The 2SLS estimator may be calculated in Stata using the ivregress 2 sls command.

12.13 Limited Information Maximum Likelihood

An alternative method to estimate the parameters of the structural equation is by maximum likelihood. Anderson and Rubin (1949) derived the maximum likelihood estimator for the joint distribution of \(\vec{Y}=\left(Y_{1}, Y_{2}\right)\). The estimator is known as limited information maximum likelihood (LIML).

This estimator is called “limited information” because it is based on the structural equation for \(Y\) combined with the reduced form equation for \(X_{2}\). If maximum likelihood is derived based on a structural equation for \(X_{2}\) as well this leads to what is known as full information maximum likelihood (FIML). The advantage of LIML relative to FIML is that the former does not require a structural model for \(X_{2}\) and thus allows the researcher to focus on the structural equation of interest - that for \(Y\). We do not describe the FIML estimator as it is not commonly used in applied econometrics.

While the LIML estimator is less widely used among economists than 2SLS it has received a resurgence of attention from econometric theorists.

To derive the LIML estimator recall the definition \(\vec{Y}=\left(Y_{1}, Y_{2}\right)\) and the reduced form (12.17)

\[ \begin{aligned} \vec{Y} &=\left[\begin{array}{cc} \lambda_{1}^{\prime} & \lambda_{2} \\ \Gamma_{12}^{\prime} & \Gamma_{22}^{\prime} \end{array}\right]\left(\begin{array}{l} Z_{1} \\ Z_{2} \end{array}\right)+u \\ &=\Pi_{1}^{\prime} Z_{1}+\Pi_{2}^{\prime} Z_{2}+u \end{aligned} \]

where \(\Pi_{1}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\lambda_{1} & \Gamma_{12}\end{array}\right]\) and \(\Pi_{2}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\lambda_{2} & \Gamma_{22}\end{array}\right]\). The LIML estimator is derived under the assumption that \(u\) is multivariate normal.

Define \(\gamma^{\prime}=\left[\begin{array}{ll}1 & -\beta_{2}^{\prime}\end{array}\right]\). From (12.15) we find

\[ \Pi_{2} \gamma=\lambda_{2}-\Gamma_{22} \beta_{2}=0 . \]

Thus the \(\ell_{2} \times\left(k_{2}+1\right)\) coefficient matrix \(\Pi_{2}\) in (12.33) has deficient rank. Indeed, its rank must be \(k_{2}\) because \(\Gamma_{22}\) has full rank.

This means that the model (12.33) is precisely the reduced rank regression model of Section \(11.11 .\) Theorem \(11.7\) presents the maximum likelihood estimators for the reduced rank parameters. In particular, the MLE for \(\gamma\) is

\[ \widehat{\gamma}=\underset{\gamma}{\operatorname{argmin}} \frac{\gamma^{\prime} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}} \gamma}{\gamma^{\prime} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}} \gamma} \]

where \(\boldsymbol{M}_{1}=\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1}^{\prime}\) and \(\boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}=\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime}\). The minimization (12.34) is sometimes called the “least variance ratio” problem.

The minimization problem (12.34) is invariant to the scale of \(\gamma\) (that is, \(\widehat{\gamma} c\) is equivalently the argmin for any c) so normalization is required. A convenient choice is \(\gamma^{\prime} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{Z} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}} \gamma=1\). Using this normalization and the theory of the minimum of quadratic forms (Section A.15) \(\widehat{\gamma}\) is the generalized eigenvector of \(\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}\) with respect to \(\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{Z} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}\) associated with the smallest generalized eigenvalue. (See Section A.14 for the definition of generalized eigenvalues and eigenvectors.) Computationally this is straightforward. For example, in MATLAB the generalized eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}\) with respect to \(\boldsymbol{B}\) is found by the command eig \((\boldsymbol{A}, \boldsymbol{B})\). Once this \(\widehat{\gamma}\) is found any other normalization can be obtained by rescaling. For example, to obtain the MLE for \(\beta_{2}\) make the partition \(\widehat{\gamma}^{\prime}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\widehat{\gamma}_{1} & \widehat{\gamma}_{2}^{\prime}\end{array}\right]\) and set \(\widehat{\beta}_{2}=-\widehat{\gamma}_{2} / \widehat{\gamma}_{1}\).

To obtain the MLE for \(\beta_{1}\) recall the structural equation \(Y_{1}=Z_{1}^{\prime} \beta_{1}+Y_{2}^{\prime} \beta_{2}+e\). Replace \(\beta_{2}\) with the MLE \(\widehat{\beta}_{2}\) and apply regression. This yields

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{1}=\left(Z_{1}^{\prime} Z_{1}\right)^{-1} Z_{1}^{\prime}\left(Y_{1}-Y_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right) . \]

These solutions are the MLE for the structural parameters \(\beta_{1}\) and \(\beta_{2}\).

Previous econometrics textbooks did not present a derivation of the LIML estimator as the original derivation by Anderson and Rubin (1949) is lengthy and not particularly insightful. In contrast the derivation given here based on reduced rank regression is simple.

There is an alternative (and traditional) expression for the LIML estimator. Define the minimum obtained in (12.34)

\[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{\kappa}}=\min _{\gamma} \frac{\gamma^{\prime} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}} \gamma}{\gamma^{\prime} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}} \gamma} \]

which is the smallest generalized eigenvalue of \(\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}\) with respect to \(\overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \overrightarrow{\boldsymbol{Y}}\). The LIML estimator can be written as

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\text {liml }}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) . \]

We defer the derivation of (12.37) until the end of this section. Expression (12.37) does not simplify computation (because \(\widehat{\kappa}\) requires solving the same eigenvector problem that yields \(\widehat{\beta}_{2}\) ). However (12.37) is important for the distribution theory. It also helps reveal the algebraic connection between LIML, least squares, and 2SLS.

The estimator (12.37) with arbitrary \(\kappa\) is known as a k-class estimator of \(\beta\). While the LIML estimator obtains by setting \(\kappa=\widehat{\kappa}\), the least squares estimator is obtained by setting \(\kappa=0\) and 2SLS is obtained by setting \(\kappa=1\). It is worth observing that the LIML solution satisfies \(\widehat{\kappa} \geq 1\). When the model is just-identified the LIML estimator is identical to the IV and 2SLS estimators. They are only different in the over-identified setting. (One corollary is that under just-identification and normal errors the IV estimator is MLE.)

For inference it is useful to observe that (12.37) shows that \(\widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{liml}}\) can be written as an IV estimator

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{liml}}=\left(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1}\right) \]

using the instrument

\[ \widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}}=\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{X}=\left(\begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol{X}_{1} \\ \boldsymbol{X}_{2}-\widehat{\kappa} \widehat{\boldsymbol{U}}_{2} \end{array}\right) \]

where \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{U}}_{2}=\boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}} \boldsymbol{X}_{2}\) are the reduced-form residuals from the multivariate regression of the endogenous regressors \(Y_{2}\) on the instruments \(Z\). Expressing LIML using this IV formula is useful for variance estimation.

The LIML estimator has the same asymptotic distribution as 2SLS. However, they have quite different behaviors in finite samples. There is considerable evidence that the LIML estimator has reduced finite sample bias relative to 2 SLS when there are many instruments or the reduced form is weak. (We review these cases in the following sections.) However, on the other hand LIML has wider finite sample dispersion.

We now derive the expression (12.37). Use the normalization \(\gamma^{\prime}=\left[\begin{array}{ll}1 & -\beta_{2}^{\prime}\end{array}\right]\) to write (12.34) as

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{2}=\underset{\beta_{2}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \frac{\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \beta_{2}\right)^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \beta_{2}\right)}{\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y} \beta_{2}\right)^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \beta_{2}\right)} . \]

The first-order-condition for minimization is \(2 /\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)\) times

\[ \begin{aligned} 0 &=\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)-\frac{\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)}{\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)} \boldsymbol{X}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right) \\ &=\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{1}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{X}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right) \end{aligned} \]

using definition (12.36). Rewriting,

\[ \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{M}_{1}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{X}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}=\boldsymbol{X}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{M}_{1}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} . \]

Equation (12.37) is the same as the two equation system

\[ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1} \widehat{\beta}_{1}+\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2} &=\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \\ \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1} \widehat{\beta}_{1}+\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}\right) \widehat{\beta}_{2} &=\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} . \end{aligned} \]

The first equation is (12.35). Using (12.35), the second is

\[ \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}_{1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}_{1}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{1}-\boldsymbol{Y}_{2} \widehat{\beta}_{2}\right)+\left(\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{2}\right) \widehat{\beta}_{2}=\boldsymbol{Y}_{2}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\widehat{\kappa} \boldsymbol{M}_{\boldsymbol{Z}}\right) \boldsymbol{Y}_{1} \]

which is (12.38) when rearranged. We have thus shown that (12.37) is equivalent to (12.35) and (12.38) and is thus a valid expression for the LIML estimator.

Returning to the Card college proximity example we now present the LIML estimates of the equation with the two instruments (public, private). They are reported in the final column of Table 12.1. They are quite similar to the 2SLS estimates.

The LIML estimator may be calculated in Stata using the ivregress liml command.

| Theodore Anderson |

|---|

| Theodore (Ted) Anderson (1918-2016) was a American statistician and econo- |

| metrician, who made fundamental contributions to multivariate statistical the- |

| ory. Important contributions include the Anderson-Darling distribution test, the |

| Anderson-Rubin statistic, the method of reduced rank regression, and his most |

| famous econometrics contribution - the LIML estimator. He continued working |

| throughout his long life, even publishing theoretical work at the age of 97 ! |

12.14 Split-Sample IV and JIVE

The ideal instrument for estimation of \(\beta\) is \(W=\Gamma^{\prime} Z\). We can write the ideal IV estimator as

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\text {ideal }}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} W_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} W_{i} Y_{i}\right) . \]

This estimator is not feasible since \(\Gamma\) is unknown. The 2SLS estimator replaces \(\Gamma\) with the multivariate least squares estimator \(\widehat{\Gamma}\) and \(W_{i}\) with \(\widehat{W}_{i}=\widehat{\Gamma}^{\prime} Z_{i}\) leading to the following representation for 2SLS

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{W}_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{W}_{i} Y_{i}\right) . \]

Since \(\widehat{\Gamma}\) is estimated on the full sample including observation \(i\) it is a function of the reduced form error \(u\) which is correlated with the structural error \(e\). It follows that \(\widehat{W}\) and \(e\) are correlated, which means that \(\widehat{\beta}_{2 s l s}\) is biased for \(\beta\). This correlation and bias disappears asymptotically but it can be important in applications.

A possible solution to this problem is to replace \(\widehat{W}\) with a predicted value which is uncorrelated with the error \(e\). One method is the split-sample IV (SSIV) estimator of Angrist and Krueger (1995). Divide the sample randomly into two independent halves \(A\) and \(B\). Use \(A\) to estimate the reduced form and \(B\) to estimate the structural coefficient. Specifically, use sample \(A\) to construct \(\widehat{\Gamma}_{A}=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}_{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}_{A}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}_{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}_{A}\right)\). Combine this with sample \(B\) to create the predicted values \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{W}}_{B}=Z_{B} \widehat{\Gamma}_{A}\). The SSIV estimator is \(\widehat{\beta}_{\text {ssiv }}=\) \(\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{W}}_{B}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}_{B}\right)^{-1}\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{W}}_{B}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}_{B}\right)\). This has lower bias than \(\widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls. }}\)

A limitation of SSIV is that the results will be sensitive to the sample spliting. One split will produce one estimator; another split will produce a different estimator. Any specific split is arbitrary, so the estimator depends on the specific random sorting of the observations into the samples \(A\) and \(B\). A second limitation of SSIV is that it is unlikely to work well when the sample size \(n\) is small.

A much better solution is obtained by a leave-one-out estimator for \(\Gamma\). Specifically, let

\[ \widehat{\Gamma}_{(-i)}=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}-Z_{i} Z_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}-Z_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right) \]

be the least squares leave-one-out estimator of the reduced form matrix \(\Gamma\), and let \(\widehat{W}_{i}=\widehat{\Gamma}_{(-i)}^{\prime} Z_{i}\) be the reduced form predicted values. Using \(\widehat{W}_{i}=\widehat{\Gamma}_{(-i)}^{\prime} Z_{i}\) as an instrument we obtain the estimator

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{jive1}}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{W}_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{W}_{i} Y_{i}\right)=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{\Gamma}_{(-i)}^{\prime} Z_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{\Gamma}_{(-i)}^{\prime} Z_{i} Y_{i}\right) . \]

This was called the jackknife instrumental variables (JIVE1) estimator by Angrist, Imbens, and Krueger (1999). It first appeared in Phillips and Hale (1977).

Angrist, Imbens, and Krueger (1999) pointed out that a somewhat simpler adjustment also removes the correlation and bias. Define the estimator and predicted value

\[ \begin{aligned} \widetilde{\Gamma}_{(-i)} &=\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}-Z_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right) \\ \widetilde{W}_{i} &=\widetilde{\Gamma}_{(-i)}^{\prime} Z_{i} \end{aligned} \]

which only adjusts the \(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\) component. Their JIVE2 estimator is

\[ \widehat{\beta}_{\mathrm{jive} 2}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widetilde{W}_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widetilde{W}_{i} Y_{i}\right)=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widetilde{\Gamma}_{(-i)}^{\prime} Z_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widetilde{\Gamma}_{(-i)}^{\prime} Z_{i} Y_{i}\right) . \]

Using the formula for leave-one-out estimators (Theorem 3.7), the JIVE1 and JIVE2 estimators use two linear operations: the first to create the predicted values \(\widehat{W}_{i}\) or \(\widetilde{W}_{i}\), and the second to calculate the IV estimator. Thus the estimators do not require significantly more computation than 2SLS.

An asymptotic distribution theory for JIVE1 and JIVE2 was developed by Chao, Swanson, Hausman, Newey, and Woutersen (2012).

The JIVE1 and JIVE2 estimators may be calculated in Stata using the \(j\) ive command. It is not a part of the standard package but can be easily added.

12.15 Consistency of 2SLS

We now demonstrate the consistency of the 2SLS estimator for the structural parameter. The following is a set of regularity conditions.

Assumption $12.1

The variables \(\left(Y_{1 i}, X_{i}, Z_{i}\right), i=1, \ldots, n\), are independent and identically distributed.

\(\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{1}^{2}\right]<\infty\).

\(\mathbb{E}\|X\|^{2}<\infty\).

\(\mathbb{E}\|Z\|^{2}<\infty\)

\(\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]\) is positive definite.

\(\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right]\) has full rank \(k\).

\(\mathbb{E}[Z e]=0\).

Assumptions 12.1.2-4 state that all variables have finite variances. Assumption 12.1.5 states that the instrument vector has an invertible design matrix, which is identical to the core assumption about regressors in the linear regression model. This excludes linearly redundant instruments. Assumptions 12.1.6 and 12.1.7 are the key identification conditions for instrumental variables. Assumption 12.1.6 states that the instruments and regressors have a full-rank cross-moment matrix. This is often called the relevance condition. Assumption 12.1.7 states that the instrumental variables and structural error are uncorrelated. Assumptions 12.1.5-7 are identical to Definition 12.1.

Theorem 12.1 Under Assumption 12.1, \(\widehat{\beta}_{2 s l s} \underset{p}{\longrightarrow} \beta\) as \(n \rightarrow \infty\).

The proof of the theorem is provided below.

This theorem shows that the 2SLS estimator is consistent for the structural coefficient \(\beta\) under similar moment conditions as the least squares estimator. The key differences are the instrumental variables assumption \(\mathbb{E}[Z e]=0\) and the relevance condition \(\operatorname{rank}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right]\right)=k\).

The result includes the IV estimator (when \(\ell=k\) ) as a special case.

The proof of this consistency result is similar to that for least squares. Take the structural equation \(\boldsymbol{Y}=\boldsymbol{X} \beta+\boldsymbol{e}\) in matrix format and substitute it into the expression for the estimator. We obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }} &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime}(\boldsymbol{X} \beta+\boldsymbol{e}) \\ &=\beta+\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{e} . \end{aligned} \]

This separates out the stochastic component. Re-writing and applying the WLLN and CMT

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta}_{2 s l s}-\beta &=\left(\left(\frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)\left(\frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\right)^{-1} \\ & \times\left(\frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)\left(\frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Z}\right)^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{Z}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{e}\right) \\ \underset{p}{\rightarrow}\left(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \mathbb{E}[Z e]=0 \end{aligned} \]

where

\[ \begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z}=\mathbb{E}\left[X Z^{\prime}\right] \\ &\boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right] \\ &\boldsymbol{Q}_{Z X}=\mathbb{E}\left[Z X^{\prime}\right] . \end{aligned} \]

The WLLN holds under Assumptions 12.1.1 and 12.1.2-4. The continuous mapping theorem applies if the matrices \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}\) and \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z X}\) are invertible, which hold under Assumptions 12.1.5 and 12.1.6. The final equality uses Assumption 12.1.7.

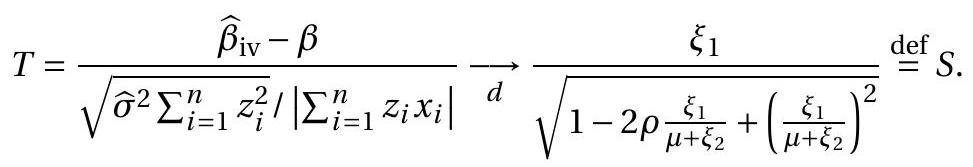

12.16 Asymptotic Distribution of 2SLS

We now show that the 2SLS estimator satisfies a central limit theorem. We first state a set of sufficient regularity conditions. Assumption 12.2 In addition to Assumption 12.1,

\(\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{1}^{4}\right]<\infty\).

\(\mathbb{E}\|X\|^{4}<\infty\).

\(\mathbb{E}\|Z\|^{4}<\infty\).

\(\Omega=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime} e^{2}\right]\) is positive definite.

Assumption \(12.2\) strengthens Assumption \(12.1\) by requiring that the dependent variable and instruments have finite fourth moments. This is used to establish the central limit theorem.

Theorem 12.2 Under Assumption 12.2, as \(n \rightarrow \infty\).

\[ \sqrt{n}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{2 \text { sls }}-\beta\right) \underset{d}{\longrightarrow} \mathrm{N}\left(0, V_{\beta}\right) \]

where

\[ \boldsymbol{V}_{\beta}=\left(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \Omega \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z X}\right)^{-1} \]

This shows that the 2 SLS estimator converges at a \(\sqrt{n}\) rate to a normal random vector. It shows as well the form of the covariance matrix. The latter takes a substantially more complicated form than the least squares estimator.

As in the case of least squares estimation the asymptotic variance simplifies under a conditional homoskedasticity condition. For 2SLS the simplification occurs when \(\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid Z\right]=\sigma^{2}\). This holds when \(Z\) and \(e\) are independent. It may be reasonable in some contexts to conceive that the error \(e\) is independent of the excluded instruments \(Z_{2}\), since by assumption the impact of \(Z_{2}\) on \(Y\) is only through \(X\), but there is no reason to expect \(e\) to be independent of the included exogenous variables \(X_{1}\). Hence heteroskedasticity should be equally expected in 2SLS and least squares regression. Nevertheless, under homoskedasticity we have the simplifications \(\Omega=\boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z} \sigma^{2}\) and \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\beta}=\boldsymbol{V}_{\beta}^{0} \stackrel{\text { def }}{=}\left(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Z} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z Z}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{Z X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2}\).

The derivation of the asymptotic distribution builds on the proof of consistency. Using equation (12.39) we have