Chapter 2: Conditional Expectation and Projection

2 Conditional Expectation and Projection

2.1 Introduction

The most commonly applied econometric tool is least squares estimation, also known as regression. Least squares is a tool to estimate the conditional mean of one variable (the dependent variable) given another set of variables (the regressors, conditioning variables, or covariates).

In this chapter we abstract from estimation and focus on the probabilistic foundation of the conditional expectation model and its projection approximation. This includes a review of probability theory. For a background in intermediate probability theory see Chapters 1-5 of Probability and Statistics for Economists.

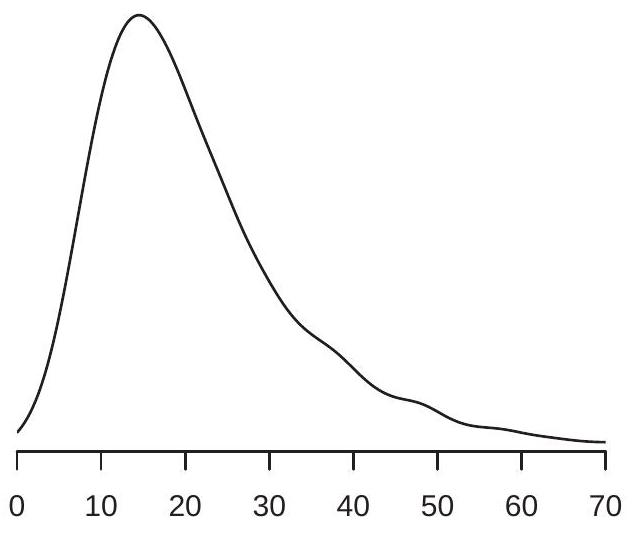

2.2 The Distribution of Wages

Suppose that we are interested in wage rates in the United States. Since wage rates vary across workers we cannot describe wage rates by a single number. Instead, we can describe wages using a probability distribution. Formally, we view the wage of an individual worker as a random variable wage with the probability distribution

\[ \begin{aligned} F(y)=\mathbb{P}[\text { wage } \leq y] \end{aligned} \tag{1}\]

When we say that a person’s wage is random we mean that we do not know their wage before it is measured, and we treat observed wage rates as realizations from the distribution \(F\). Treating unobserved wages as random variables and observed wages as realizations is a powerful mathematical abstraction which allows us to use the tools of mathematical probability.

A useful thought experiment is to imagine dialing a telephone number selected at random, and then asking the person who responds to tell us their wage rate. (Assume for simplicity that all workers have equal access to telephones and that the person who answers your call will answer honestly.) In this thought experiment, the wage of the person you have called is a single draw from the distribution \(F\) of wages in the population. By making many such phone calls we can learn the full distribution.

When a distribution function \(F\) is differentiable we define the probability density function

\[ \begin{aligned} f(y)=\frac{d}{d y} F(y) \end{aligned} \tag{2}\]

The density contains the same information as the distribution function, but the density is typically easier to visually interpret.

.jpg)

In Figure 2.1(a) we display an estimate \({ }^{1}\) of the probability density function of U.S. wage rates in \(2009 .\) We see that the density is peaked around \(\$ 15\), and most of the probability mass appears to lie between \(\$ 10\) and \(\$ 40\). These are ranges for typical wage rates in the U.S. population.

Important measures of central tendency are the median and the mean. The median \(m\) of a continuous distribution \(F\) is the unique solution to

\[ F(m)=\frac{1}{2} . \]

The median U.S. wage is \(\$ 19.23\). The median is a robust \({ }^{2}\) measure of central tendency, but it is tricky to use for many calculations as it is not a linear operator.

The mean or expectation of a random variable \(Y\) with discrete support is

\[ \mu=\mathbb{E}[Y]=\sum_{j=1}^{\infty} \tau_{j} \mathbb{P}\left[Y=\tau_{j}\right] . \]

For a continuous random variable with density \(f(y)\) the expectation is

\[ \mu=\mathbb{E}[Y]=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} y f(y) d y . \]

Here we have used the common and convenient convention of using the single character \(Y\) to denote a random variable, rather than the more cumbersome label wage. An alternative notation which includes both discrete and continuous random variables as special cases is to write the integral as \(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} y d F(y)\).

The expectation is a convenient measure of central tendency because it is a linear operator and arises naturally in many economic models. A disadvantage of the expectation is that it is not robust \({ }^{3}\) especially

\({ }^{1}\) The distribution and density are estimated nonparametrically from the sample of 50,742 full-time non-military wageearners reported in the March 2009 Current Population Survey. The wage rate is constructed as annual individual wage and salary earnings divided by hours worked.

\({ }^{2}\) The median is not sensitive to pertubations in the tails of the distribution.

\({ }^{3}\) The expectation is sensitive to pertubations in the tails of the distribution. in the presence of substantial skewness or thick tails, both which are features of the wage distribution as can be seen in Figure 2.1(a). Another way of viewing this is that \(64 %\) of workers earn less than the mean wage of \(\$ 23.90\), suggesting that it is incorrect to describe the mean \(\$ 23.90\) as a “typical” wage rate.

In this context it is useful to transform the data by taking the natural logarithm” \({ }^{4}\). Figure \(2.1\) (b) shows the density of \(\log\) hourly wages \(\log (\) wage \()\) for the same population. The density of log wages is less skewed and fat-tailed than the density of the level of wages, so its mean

\[ \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage })]=2.95 \]

is a better (more robust) measure \({ }^{5}\) of central tendency of the distribution. For this reason, wage regressions typically use log wages as a dependent variable rather than the level of wages.

Another useful way to summarize the probability distribution \(F(y)\) is in terms of its quantiles. For any \(\alpha \in(0,1)\), the \(\alpha^{t h}\) quantile of the continuous \({ }^{6}\) distribution \(F\) is the real number \(q_{\alpha}\) which satisfies \(F\left(q_{\alpha}\right)=\alpha\). The quantile function \(q_{\alpha}\), viewed as a function of \(\alpha\), is the inverse of the distribution function \(F\). The most commonly used quantile is the median, that is, \(q_{0.5}=m\). We sometimes refer to quantiles by the percentile representation of \(\alpha\) and in this case they are called percentiles. E.g. the median is the \(50^{t h}\) percentile.

2.3 Conditional Expectation

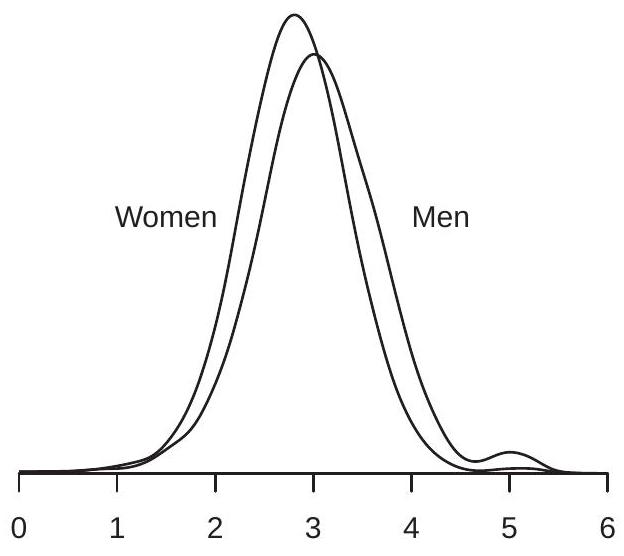

We saw in Figure 2.1(b) the density of log wages. Is this distribution the same for all workers, or does the wage distribution vary across subpopulations? To answer this question, we can compare wage distributions for different groups - for example, men and women. To investigate, we plot in Figure \(2.2\) (a) the densities of log wages for U.S. men and women. We can see that the two wage densities take similar shapes but the density for men is somewhat shifted to the right.

The values \(3.05\) and \(2.81\) are the mean log wages in the subpopulations of men and women workers. They are called the conditional expectation (or conditional mean) of log wages given gender. We can write their specific values as

\[ \begin{gathered} \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man }]=3.05 \\ \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { woman }]=2.81 . \end{gathered} \]

We call these expectations “conditional” as they are conditioning on a fixed value of the variable gender. While you might not think of a person’s gender as a random variable, it is random from the viewpoint of econometric analysis. If you randomly select an individual, the gender of the individual is unknown and thus random. (In the population of U.S. workers, the probability that a worker is a woman happens to be \(43 %\).) In observational data, it is most appropriate to view all measurements as random variables, and the means of subpopulations are then conditional means.

It is important to mention at this point that we in no way attribute causality or interpretation to the difference in the conditional expectation of log wages between men and women. There are multiple potential explanations.

As the two densities in Figure 2.2(a) appear similar, a hasty inference might be that there is not a meaningful difference between the wage distributions of men and women. Before jumping to this conclusion let us examine the differences in the distributions more carefully. As we mentioned above, the

\({ }^{4}\) Throughout the text, we will use \(\log (y)\) or \(\log y\) to denote the natural logarithm of \(y\).

\({ }^{5}\) More precisely, the geometric mean \(\exp (\mathbb{E}[\log W])=\$ 19.11\) is a robust measure of central tendency.

\({ }^{6}\) If \(F\) is not continuous the definition is \(q_{\alpha}=\inf \{y: F(y) \geq \alpha\}\)

- Women and Men

.jpg)

- By Gender and Race

Figure 2.2: Log Wage Density by Gender and Race

primary difference between the two densities appears to be their means. This difference equals

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man }]-\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { woman }] &=3.05-2.81 \\ &=0.24 . \end{aligned} \]

A difference in expected log wages of \(0.24\) is often interpreted as an average \(24 %\) difference between the wages of men and women, which is quite substantial. (For a more complete explanation see Section 2.4.)

Consider further splitting the male and female subpopulations by race, dividing the population into whites, Blacks, and other races. We display the log wage density functions of four of these groups in Figure \(2.2\) (b). Again we see that the primary difference between the four density functions is their central tendency.

Focusing on the means of these distributions, Table \(2.1\) reports the mean log wage for each of the six sub-populations.

Table 2.1: Mean Log Wages by Gender and Race

| men | women | |

|---|---|---|

| white | \(3.07\) | \(2.82\) |

| Black | \(2.86\) | \(2.73\) |

| other | \(3.03\) | \(2.86\) |

Once again we stress that we in no way attribute causality or interpretation to the differences across the entries of the table. The reason why we use these particular sub-populations to illustrate conditional expectation is because differences in economic outcomes between gender and racial groups in the United States (and elsewhere) are widely discussed; part of the role of social science is to carefully document such patterns, and part of its role is to craft models and explanations. Conditional expectations (by themselves) can help in the documentation and description; conditional expectations by themselves are neither a model nor an explanation.

The entries in Table \(2.1\) are the conditional means of \(\log (\) wage \()\) given gender and race. For example

\[ \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man, race }=\text { white }]=3.07 \]

and

\[ \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { woman, race }=\text { Black }]=2.73 \text {. } \]

One benefit of focusing on conditional means is that they reduce complicated distributions to a single summary measure, and thereby facilitate comparisons across groups. Because of this simplifying property, conditional means are the primary interest of regression analysis and are a major focus in econometrics.

Table \(2.1\) allows us to easily calculate average wage differences between groups. For example, we can see that the wage gap between men and women continues after disaggregation by race, as the average gap between white men and white women is \(25 %\), and that between Black men and Black women is \(13 %\). We also can see that there is a race gap, as the average wages of Blacks are substantially less than the other race categories. In particular, the average wage gap between white men and Black men is \(21 %\), and that between white women and Black women is \(9 %\).

2.4 Logs and Percentages

In this section we want to motivate and clarify the use of the logarithm in regression analysis by making two observations. First, when applied to numbers the difference of logarithms approximately equals the percentage difference. Second, when applied to averages the difference in logarithms approximately equals the percentage difference in the geometric mean. We now explain these ideas and the nature of the approximations involved.

Take two positive numbers \(a\) and \(b\). The percentage difference between \(a\) and \(b\) is

\[ p=100\left(\frac{a-b}{b}\right) . \]

Rewriting,

\[ \frac{a}{b}=1+\frac{p}{100} \]

Taking natural logarithms,

\[ \log a-\log b=\log \left(1+\frac{p}{100}\right) . \]

A useful approximation for small \(x\) is

\[ \log (1+x) \simeq x . \]

This can be derived from the infinite series expansion of \(\log (1+x)\) :

\[ \log (1+x)=x-\frac{x^{2}}{2}+\frac{x^{3}}{3}-\frac{x^{4}}{4}+\cdots=x+O\left(x^{2}\right) . \]

The symbol \(O\left(x^{2}\right.\) ) means that the remainder is bounded by \(A x^{2}\) as \(x \rightarrow 0\) for some \(A<\infty\). Numerically, the approximation \(\log (1+x) \simeq x\) is within \(0.001\) for \(|x| \leq 0.1\), and the approximation error increases with \(|x|\)

Applying (2.3) to (2.2) and multiplying by 100 we find

\[ p \simeq 100(\log a)-\log b) . \]

This shows that 100 multiplied by the difference in logarithms is approximately the percentage difference. Numerically, the approximation error is less than \(0.1\) percentage points for \(|p| \leq 10\).

Now consider the difference in the expectation of log transformed random variables. Take two random variables \(X_{1}, X_{2}>0\). Define their geometric means \(\theta_{1}=\exp \left(\mathbb{E}\left[\log X_{1}\right]\right)\) and \(\theta_{2}=\exp \left(\mathbb{E}\left[\log X_{2}\right]\right)\) and their percentage difference

\[ p=100\left(\frac{\theta_{2}-\theta_{1}}{\theta_{1}}\right) . \]

The difference in the expectation of the log transforms (multiplied by 100) is

\[ 100\left(\mathbb{E}\left[\log X_{2}\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[\log X_{1}\right]\right)=100\left(\log \theta_{2}-\log \theta_{1}\right) \simeq p \]

the percentage difference between \(\theta_{2}\) and \(\theta_{1}\). In words, the difference between the average of the log transformed variables is (approximately) the percentage difference in the geometric means.

The reason why this latter observation is important is because many econometric equations take the semi-log form

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathbb{E}[\log Y \mid \operatorname{group}=1]=\mu_{1} \\ &\mathbb{E}[\log Y \mid \operatorname{group}=2]=\mu_{2} \end{aligned} \]

and considerable attention is given to the difference \(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2}\). For example, in the previous section we compared the average log wages for men and women and found that the difference is \(0.24\). In that section we stated that this difference is often interpreted as the average percentage difference. This is not quite right, but is not quite wrong either. What the above calculation shows is that this difference is approximately the percentage difference in the geometric mean. So \(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2}\) is an average percentage difference, where “average” refers to geometric rather than arithmetic mean.

To compare different measures of percentage difference see Table 2.2. In the first two columns we report average wages for men and women in the CPS population using four “averages”: arithmetic mean, median, geometric mean, and mean log. For both groups the arithmetic mean is higher than the median and geometric mean, and the latter two are similar to one another. This is a common feature of skewed distributions such as the wage distribution. The third column reports the percentage difference between the first two columns (using men’s wages as the base). For example, the first entry of \(34 %\) states that the mean wage for men is \(34 %\) higher than the mean wage for women. The next entries show that the median and geometric mean for men is \(26 %\) higher than those for women. The final entry in this column is 100 times the simple difference between the mean log wage, which is \(24 %\). As shown above, the difference in the mean of the log transformation is approximately the percentage difference in the geometric mean, and this approximation is excellent for differences under \(10 %\).

Let’s summarize this analysis. It is common to take logarithms of variables and make comparisons between conditional means. We have shown that these differences are measures of the percentage difference in the geometric mean. Thus the common description that the difference between expected log transforms (such as the \(0.24\) difference between those for men and women’s wages) is an approximate percentage difference (e.g. a 24% difference in men’s wages relative to women’s) is correct, so long as we realize that we are implicitly comparing geometric means.

2.5 Conditional Expectation Function

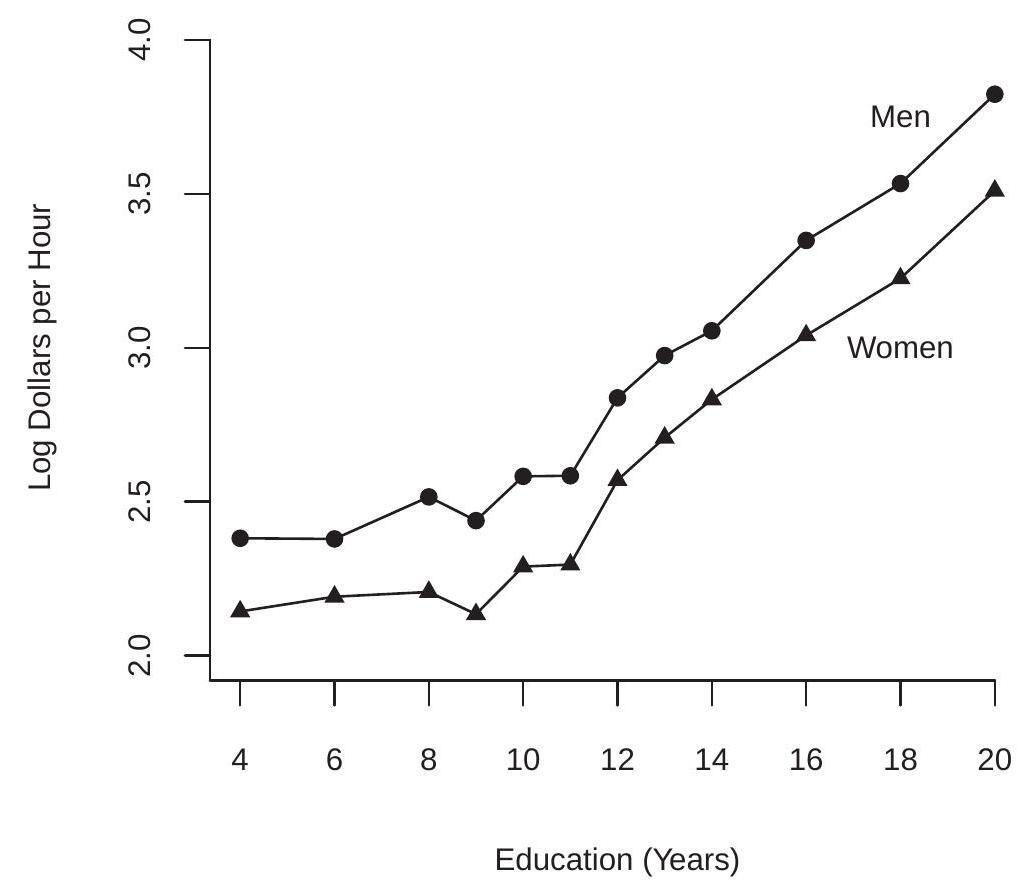

An important determinant of wages is education. In many empirical studies economists measure educational attainment by the number of years \({ }^{7}\) of schooling. We will write this variable as education.

\({ }^{7}\) Here, education is defined as years of schooling beyond kindergarten. A high school graduate has education=12, a college graduate has education=16, a Master’s degree has education=18, and a professional degree (medical, law or PhD) has educa- Table 2.2: Average Wages and Percentage Differences

| men | women | % Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic Mean | \(\$ 26.80\) | \(\$ 20.00\) | \(34 %\) |

| Median | \(\$ 21.14\) | \(\$ 16.83\) | \(26 %\) |

| Geometric Mean | \(\$ 21.03\) | \(\$ 16.64\) | \(26 %\) |

| Mean log Wage | \(3.05\) | \(2.81\) | \(24 %\) |

The conditional expectation of \(\log (\) wage \()\) given gender, race, and education is a single number for each category. For example

\[ \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man, race }=\text { white, education }=12]=2.84 . \]

We display in Figure \(2.3\) the conditional expectation of \(\log\) (wage) as a function of education, separately for (white) men and women. The plot is quite revealing. We see that the conditional expectation is increasing in years of education, but at a different rate for schooling levels above and below nine years. Another striking feature of Figure \(2.3\) is that the gap between men and women is roughly constant for all education levels. As the variables are measured in logs this implies a constant average percentage gap between men and women regardless of educational attainment.

Figure 2.3: Expected Log Wage as a Function of Education tion=20. In many cases it is convenient to simplify the notation by writing variables using single characters, typically \(Y, X\), and/or \(Z\). It is conventional in econometrics to denote the dependent variable (e.g. \(\log (\) wage \()\) ) by the letter \(Y\), a conditioning variable (such as gender) by the letter \(X\), and multiple conditioning variables (such as race, education and gender) by the subscripted letters \(X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots, X_{k}\).

Conditional expectations can be written with the generic notation

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}=x_{1}, X_{2}=x_{2}, \ldots, X_{k}=x_{k}\right]=m\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}\right) \text {. } \]

We call this the conditional expectation function (CEF). The CEF is a function of \(\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}\right)\) as it varies with the variables. For example, the conditional expectation of \(Y=\log (\) wage \()\) given \(\left(X_{1}, X_{2}\right)=(g e n d e r\), race) is given by the six entries of Table \(2.1 .\)

For greater compactness we typically write the conditioning variables as a vector in \(\mathbb{R}^{k}\) :

\[ X=\left(\begin{array}{c} X_{1} \\ X_{2} \\ \vdots \\ X_{k} \end{array}\right) \]

Given this notation, the CEF can be compactly written as

\[ \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X=x]=m(x) . \]

The CEF \(m(x)=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X=x]\) is a function of \(x \in \mathbb{R}^{k}\). It says: “When \(X\) takes the value \(x\) then the average value of \(Y\) is \(m(x)\).” Sometimes it is useful to view the CEF as a function of the random variable \(X\). In this case we evaluate the function \(m(x)\) at \(X\), and write \(m(X)\) or \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\). This is random as it is a function of the random variable \(X\).

2.6 Continuous Variables

In the previous sections we implicitly assumed that the conditioning variables are discrete. However, many conditioning variables are continuous. In this section, we take up this case and assume that the variables \((Y, X)\) are continuously distributed with a joint density function \(f(y, x)\).

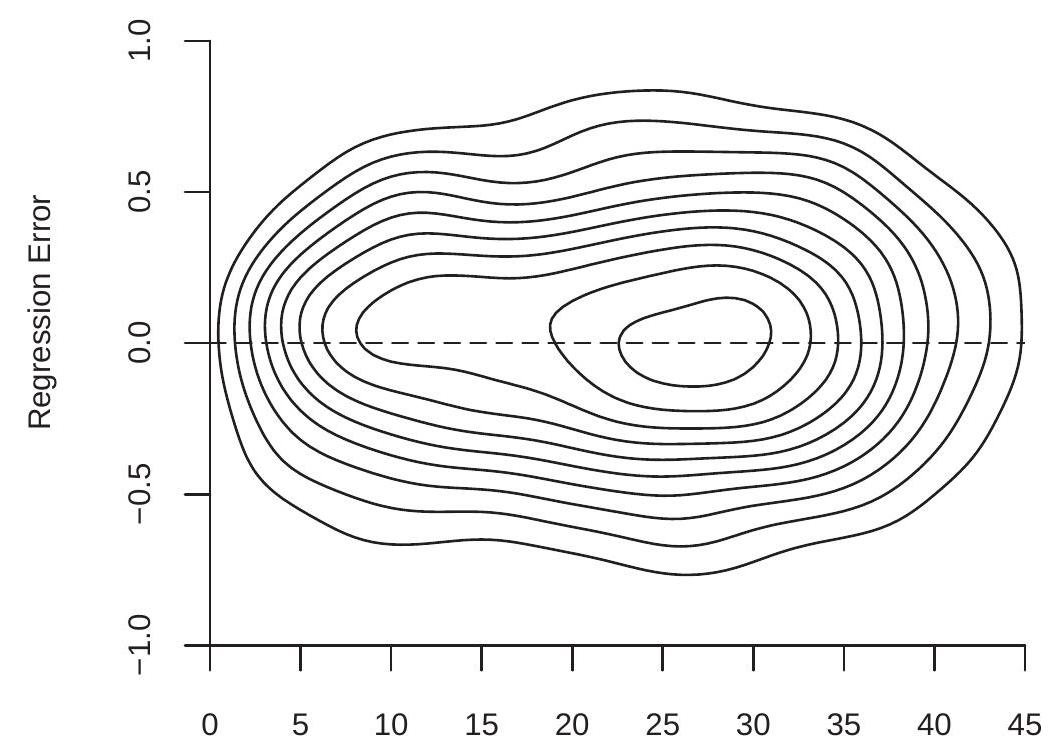

As an example, take \(Y=\log (\) wage \()\) and \(X=\) experience, the latter the number of years of potential labor market experience \({ }^{8}\). The contours of their joint density are plotted in Figure \(2.4\) (a) for the population of white men with 12 years of education.

Given the joint density \(f(y, x)\) the variable \(x\) has the marginal density

\[ f_{X}(x)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(y, x) d y . \]

For any \(x\) such that \(f_{X}(x)>0\) the conditional density of \(Y\) given \(X\) is defined as

\[ f_{Y \mid X}(y \mid x)=\frac{f(y, x)}{f_{X}(x)} . \]

The conditional density is a renormalized slice of the joint density \(f(y, x)\) holding \(x\) fixed. The slice is renormalized (divided by \(f_{X}(x)\) so that it integrates to one) and is thus a density. We can visualize this by slicing the joint density function at a specific value of \(x\) parallel with the \(y\)-axis. For example, take the density contours in Figure 2.4(a) and slice through the contour plot at a specific value of experience, and

\({ }^{8}\) As there is no direct measure for experience, we instead define experience as age-education-6

- Joint Density of Log Wage and Experience

.jpg)

- Conditional Density of Log Wage given Experience

Figure 2.4: Log Wage and Experience

then renormalize the slice so that it is a proper density. This gives us the conditional density of log(wage) for white men with 12 years of education and this level of experience. We do this for three levels of experience \((5,10\), and 25 years), and plot these densities in Figure \(2.4\) (b). We can see that the distribution of wages shifts to the right and becomes more diffuse as experience increases.

The CEF of \(Y\) given \(X=x\) is the expectation of the conditional density (2.5)

\[ m(x)=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X=x]=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} y f_{Y \mid X}(y \mid x) d y . \]

Intuitively, \(m(x)\) is the expectation of \(Y\) for the idealized subpopulation where the conditioning variables are fixed at \(x\). When \(X\) is continuously distributed this subpopulation is infinitely small.

This definition (2.6) is appropriate when the conditional density (2.5) is well defined. However, Theorem \(2.13\) in Section \(2.31\) will show that \(m(x)\) can be defined for any random variables \((Y, X)\) so long as \(\mathbb{E}|Y|<\infty\)

In Figure 2.4(a) the CEF of \(\log\) (wage) given experience is plotted as the solid line. We can see that the CEF is a smooth but nonlinear function. The CEF is initially increasing in experience, flattens out around experience \(=30\), and then decreases for high levels of experience.

2.7 Law of Iterated Expectations

An extremely useful tool from probability theory is the law of iterated expectations. An important special case is known as the Simple Law. Theorem 2.1 Simple Law of Iterated Expectations

If \(\mathbb{E}|Y|<\infty\) then for any random vector \(X\),

\[ \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]]=\mathbb{E}[Y] . \]

This states that the expectation of the conditional expectation is the unconditional expectation. In other words the average of the conditional averages is the unconditional average. For discrete \(X\)

\[ \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]]=\sum_{j=1}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X=x_{j}\right] \mathbb{P}\left[X=x_{j}\right] . \]

For continuous \(X\)

\[ \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]]=\int_{\mathbb{R}^{k}} \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X=x] f_{X}(x) d x . \]

Going back to our investigation of average log wages for men and women, the simple law states that

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man }] \mathbb{P}[\text { gender }=\text { man }] \\ &+\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { woman }] \mathbb{P}[\text { gender }=\text { woman }] \\ &=\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage })] \end{aligned} \]

Or numerically,

\[ 3.05 \times 0.57+2.81 \times 0.43=2.95 \text {. } \]

The general law of iterated expectations allows two sets of conditioning variables.

Theorem 2.2 Law of Iterated Expectations If \(\mathbb{E}|Y|<\infty\) then for any random vectors \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\),

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}\right] \mid X_{1}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}\right] . \]

Notice the way the law is applied. The inner expectation conditions on \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\), while the outer expectation conditions only on \(X_{1}\). The iterated expectation yields the simple answer \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}\right]\), the expectation conditional on \(X_{1}\) alone. Sometimes we phrase this as: “The smaller information set wins.”

As an example

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man, race }=\text { white }] \mathbb{P}[\text { race }=\text { white } \mid \text { gender }=\text { man }] \\ &+\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man, race }=\text { Black }] \mathbb{P}[\text { race }=\text { Black } \mid \text { gender }=\text { man }] \\ &+\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man, race }=\text { other }] \mathbb{P}[\text { race }=\text { other } \mid \text { gender }=\text { man }] \\ &=\mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { gender }=\text { man }] \end{aligned} \]

or numerically

\[ 3.07 \times 0.84+2.86 \times 0.08+3.03 \times 0.08=3.05 \text {. } \]

A property of conditional expectations is that when you condition on a random vector \(X\) you can effectively treat it as if it is constant. For example, \(\mathbb{E}[X \mid X]=X\) and \(\mathbb{E}[g(X) \mid X]=g(X)\) for any function \(g(\cdot)\). The general property is known as the Conditioning Theorem.

Theorem 2.3 Conditioning Theorem If \(\mathbb{E}|Y|<\infty\) then

\[ \mathbb{E}[g(X) Y \mid X]=g(X) \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X] . \]

If in addition \(\mathbb{E}|g(X)|<\infty\) then

\[ \mathbb{E}[g(X) Y]=\mathbb{E}[g(X) \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]] . \]

The proofs of Theorems 2.1, \(2.2\) and \(2.3\) are given in Section \(2.33 .\)

2.8 CEF Error

The CEF error \(e\) is defined as the difference between \(Y\) and the CEF evaluated at \(X\) :

\[ e=Y-m(X) . \]

By construction, this yields the formula

\[ Y=m(X)+e . \]

In (2.9) it is useful to understand that the error \(e\) is derived from the joint distribution of \((Y, X)\), and so its properties are derived from this construction.

Many authors in econometrics denote the CEF error using the Greek letter \(\varepsilon\). I do not follow this convention because the error \(e\) is a random variable similar to \(Y\) and \(X\), and it is typical to use Latin characters for random variables.

A key property of the CEF error is that it has a conditional expectation of zero. To see this, by the linearity of expectations, the definition \(m(X)=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\), and the Conditioning Theorem

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[e \mid X] &=\mathbb{E}[(Y-m(X)) \mid X] \\ &=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]-\mathbb{E}[m(X) \mid X] \\ &=m(X)-m(X)=0 . \end{aligned} \]

This fact can be combined with the law of iterated expectations to show that the unconditional expectation is also zero.

\[ \mathbb{E}[e]=\mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[e \mid X]]=\mathbb{E}[0]=0 . \]

We state this and some other results formally.

Theorem 2.4 Properties of the CEF error

If \(\mathbb{E}|Y|<\infty\) then

\(\mathbb{E}[e \mid X]=0\).

\(\mathbb{E}[e]=0\).

If \(\mathbb{E}|Y|^{r}<\infty\) for \(r \geq 1\) then \(\mathbb{E}|e|^{r}<\infty\).

For any function \(h(x)\) such that \(\mathbb{E}|h(X) e|<\infty\) then \(\mathbb{E}[h(X) e]=0\). The proof of the third result is deferred to Section 2.33. The fourth result, whose proof is left to Exercise 2.3, implies that \(e\) is uncorrelated with any function of the regressors.

The equations

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=m(X)+e \\ \mathbb{E}[e \mid X] &=0 \end{aligned} \]

together imply that \(m(X)\) is the CEF of \(Y\) given \(X\). It is important to understand that this is not a restriction. These equations hold true by definition.

The condition \(\mathbb{E}[e \mid X]=0\) is implied by the definition of \(e\) as the difference between \(Y\) and the CEF \(m(X)\). The equation \(\mathbb{E}[e \mid X]=0\) is sometimes called a conditional mean restriction, because the conditional mean of the error \(e\) is restricted to equal zero. The property is also sometimes called mean independence, for the conditional mean of \(e\) is 0 and thus independent of \(X\). However, it does not imply that the distribution of \(e\) is independent of \(X\). Sometimes the assumption ” \(e\) is independent of \(X\) ” is added as a convenient simplification, but it is not generic feature of the conditional mean. Typically and generally, \(e\) and \(X\) are jointly dependent even though the conditional mean of \(e\) is zero.

As an example, the contours of the joint density of the regression error \(e\) and experience are plotted in Figure \(2.5\) for the same population as Figure 2.4. Notice that the shape of the conditional distribution varies with the level of experience.

Labor Market Experience (Years)

Figure 2.5: Joint Density of Regression Error and Experience

As a simple example of a case where \(X\) and \(e\) are mean independent yet dependent let \(e=X u\) where \(X\) and \(u\) are independent \(\mathrm{N}(0,1)\). Then conditional on \(X\) the error \(e\) has the distribution \(\mathrm{N}\left(0, X^{2}\right)\). Thus \(\mathbb{E}[e \mid X]=0\) and \(e\) is mean independent of \(X\), yet \(e\) is not fully independent of \(X\). Mean independence does not imply full independence.

2.9 Intercept-Only Model

A special case of the regression model is when there are no regressors \(X\). In this case \(m(X)=\mathbb{E}[Y]=\mu\), the unconditional expectation of \(Y\). We can still write an equation for \(Y\) in the regression format:

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=\mu+e \\ \mathbb{E}[e] &=0 . \end{aligned} \]

This is useful for it unifies the notation.

2.10 Regression Variance

An important measure of the dispersion about the CEF function is the unconditional variance of the CEF error \(e\). We write this as

\[ \sigma^{2}=\operatorname{var}[e]=\mathbb{E}\left[(e-\mathbb{E}[e])^{2}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right] . \]

Theorem 2.4.3 implies the following simple but useful result.

Theorem 2.5 If \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty\) then \(\sigma^{2}<\infty\).

We can call \(\sigma^{2}\) the regression variance or the variance of the regression error. The magnitude of \(\sigma^{2}\) measures the amount of variation in \(Y\) which is not “explained” or accounted for in the conditional expectation \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\).

The regression variance depends on the regressors \(X\). Consider two regressions

\[ \begin{aligned} &Y=\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}\right]+e_{1} \\ &Y=\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}\right]+e_{2} . \end{aligned} \]

We write the two errors distinctly as \(e_{1}\) and \(e_{2}\) as they are different - changing the conditioning information changes the conditional expectation and therefore the regression error as well.

In our discussion of iterated expectations we have seen that by increasing the conditioning set the conditional expectation reveals greater detail about the distribution of \(Y\). What is the implication for the regression error?

It turns out that there is a simple relationship. We can think of the conditional expectation \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\) as the “explained portion” of \(Y\). The remainder \(e=Y-\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\) is the “unexplained portion”. The simple relationship we now derive shows that the variance of this unexplained portion decreases when we condition on more variables. This relationship is monotonic in the sense that increasing the amount of information always decreases the variance of the unexplained portion.

Theorem 2.6 If \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty\) then

\[ \operatorname{var}[Y] \geq \operatorname{var}\left[Y-\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}\right]\right] \geq \operatorname{var}\left[Y-\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}\right]\right] . \]

Theorem \(2.6\) says that the variance of the difference between \(Y\) and its conditional expectation (weakly) decreases whenever an additional variable is added to the conditioning information.

The proof of Theorem \(2.6\) is given in Section 2.33.

2.11 Best Predictor

Suppose that given a random vector \(X\) we want to predict or forecast \(Y\). We can write any predictor as a function \(g(X)\) of \(X\). The (ex-post) prediction error is the realized difference \(Y-g(X)\). A non-stochastic measure of the magnitude of the prediction error is the expectation of its square

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[(Y-g(X))^{2}\right] . \]

We can define the best predictor as the function \(g(X)\) which minimizes (2.10). What function is the best predictor? It turns out that the answer is the CEF \(m(X)\). This holds regardless of the joint distribution of \((Y, X)\).

To see this, note that the mean squared error of a predictor \(g(X)\) is

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[(Y-g(X))^{2}\right] &=\mathbb{E}\left[(e+m(X)-g(X))^{2}\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right]+2 \mathbb{E}[e(m(X)-g(X))]+\mathbb{E}\left[(m(X)-g(X))^{2}\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right]+\mathbb{E}\left[(m(X)-g(X))^{2}\right] \\ & \geq \mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[(Y-m(X))^{2}\right] . \end{aligned} \]

The first equality makes the substitution \(Y=m(X)+e\) and the third equality uses Theorem 2.4.4. The right-hand-side after the third equality is minimized by setting \(g(X)=m(X)\), yielding the inequality in the fourth line. The minimum is finite under the assumption \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty\) as shown by Theorem \(2.5\).

We state this formally in the following result.

Theorem 2.7 Conditional Expectation as Best Predictor If \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty\), then for any predictor \(g(X)\),

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[(Y-g(X))^{2}\right] \geq \mathbb{E}\left[(Y-m(X))^{2}\right] \]

where \(m(X)=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\)

It may be helpful to consider this result in the context of the intercept-only model

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=\mu+e \\ \mathbb{E}[e] &=0 . \end{aligned} \]

Theorem \(2.7\) shows that the best predictor for \(Y\) (in the class of constants) is the unconditional mean \(\mu=\mathbb{E}[Y]\) in the sense that the mean minimizes the mean squared prediction error.

2.12 Conditional Variance

While the conditional mean is a good measure of the location of a conditional distribution it does not provide information about the spread of the distribution. A common measure of the dispersion is the conditional variance. We first give the general definition of the conditional variance of a random variable \(Y\).

Definition 2.1 If \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty\), the conditional variance of \(Y\) given \(X=x\) is

\[ \sigma^{2}(x)=\operatorname{var}[Y \mid X=x]=\mathbb{E}\left[(Y-\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X=x])^{2} \mid X=x\right] . \]

The conditional variance treated as a random variable is \(\operatorname{var}[Y \mid X]=\sigma^{2}(X)\).

The conditional variance is distinct from the unconditional variance var \([Y]\). The difference is that the conditional variance is a function of the conditioning variables. Notice that the conditional variance is the conditional second moment, centered around the conditional first moment.

Given this definition we define the conditional variance of the regression error.

Definition 2.2 If \(\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right]<\infty\), the conditional variance of the regression error \(e\) given \(X=x\) is

\[ \sigma^{2}(x)=\operatorname{var}[e \mid X=x]=\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X=x\right] . \]

The conditional variance of \(e\) treated as a random variable is \(\operatorname{var}[e \mid X]=\sigma^{2}(X)\).

Again, the conditional variance \(\sigma^{2}(x)\) is distinct from the unconditional variance \(\sigma^{2}\). The conditional variance is a function of the regressors, the unconditional variance is not. Generally, \(\sigma^{2}(x)\) is a non-trivial function of \(x\) and can take any form subject to the restriction that it is non-negative. One way to think about \(\sigma^{2}(x)\) is that it is the conditional mean of \(e^{2}\) given \(X\). Notice as well that \(\sigma^{2}(x)=\operatorname{var}[Y \mid X=x]\) so it is equivalently the conditional variance of the dependent variable.

The variance of \(Y\) is in a different unit of measurement than \(Y\). To convert the variance to the same unit of measure we define the conditional standard deviation as its square root \(\sigma(x)=\sqrt{\sigma^{2}(x)}\).

As an example of how the conditional variance depends on observables, compare the conditional log wage densities for men and women displayed in Figure 2.2. The difference between the densities is not purely a location shift but is also a difference in spread. Specifically, we can see that the density for men’s log wages is somewhat more spread out than that for women, while the density for women’s wages is somewhat more peaked. Indeed, the conditional standard deviation for men’s wages is \(3.05\) and that for women is \(2.81\). So while men have higher average wages they are also somewhat more dispersed.

The unconditional variance is related to the conditional variance by the following identity.

Theorem 2.8 If \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty\) then

\[ \operatorname{var}[Y]=\mathbb{E}[\operatorname{var}[Y \mid X]]+\operatorname{var}[\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]] . \]

See Theorem \(4.14\) of Probability and Statistics for Economists. Theorem \(2.8\) decomposes the unconditional variance into what are sometimes called the “within group variance” and the “across group variance”. For example, if \(X\) is education level, then the first term is the expected variance of the conditional expectation by education level. The second term is the variance after controlling for education.

The regression error has a conditional mean of zero, so its unconditional error variance equals the expected conditional variance, or equivalently can be found by the law of iterated expectations.

\[ \sigma^{2}=\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X\right]\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\sigma^{2}(X)\right] . \]

That is, the unconditional error variance is the average conditional variance.

Given the conditional variance we can define a rescaled error

\[ u=\frac{e}{\sigma(X)} \text {. } \]

We calculate that since \(\sigma(X)\) is a function of \(X\)

\[ \mathbb{E}[u \mid X]=\mathbb{E}\left[\frac{e}{\sigma(X)} \mid X\right]=\frac{1}{\sigma(X)} \mathbb{E}[e \mid X]=0 \]

and

\[ \operatorname{var}[u \mid X]=\mathbb{E}\left[u^{2} \mid X\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\frac{e^{2}}{\sigma^{2}(X)} \mid X\right]=\frac{1}{\sigma^{2}(X)} \mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X\right]=\frac{\sigma^{2}(X)}{\sigma^{2}(X)}=1 . \]

Thus \(u\) has a conditional expectation of zero and a conditional variance of 1 .

Notice that (2.11) can be rewritten as

\[ e=\sigma(X) u . \]

and substituting this for \(e\) in the CEF equation (2.9), we find that

\[ Y=m(X)+\sigma(X) u . \]

This is an alternative (mean-variance) representation of the CEF equation.

Many econometric studies focus on the conditional expectation \(m(x)\) and either ignore the conditional variance \(\sigma^{2}(x)\), treat it as a constant \(\sigma^{2}(x)=\sigma^{2}\), or treat it as a nuisance parameter (a parameter not of primary interest). This is appropriate when the primary variation in the conditional distribution is in the mean but can be short-sighted in other cases. Dispersion is relevant to many economic topics, including income and wealth distribution, economic inequality, and price dispersion. Conditional dispersion (variance) can be a fruitful subject for investigation.

The perverse consequences of a narrow-minded focus on the mean is parodied in a classic joke:

An economist was standing with one foot in a bucket of boiling water and the other foot in a bucket of ice. When asked how he felt, he replied, “On average I feel just fine.”

Clearly, the economist in question ignored variance!

2.13 Homoskedasticity and Heteroskedasticity

An important special case obtains when the conditional variance \(\sigma^{2}(x)\) is a constant and independent of \(x\). This is called homoskedasticity.

Definition 2.3 The error is homoskedastic if \(\sigma^{2}(x)=\sigma^{2}\) does not depend on \(x\).

In the general case where \(\sigma^{2}(x)\) depends on \(x\) we say that the error \(e\) is heteroskedastic.

Definition 2.4 The error is heteroskedastic if \(\sigma^{2}(x)\) depends on \(x\).

It is helpful to understand that the concepts homoskedasticity and heteroskedasticity concern the conditional variance, not the unconditional variance. By definition, the unconditional variance \(\sigma^{2}\) is a constant and independent of the regressors \(X\). So when we talk about the variance as a function of the regressors we are talking about the conditional variance \(\sigma^{2}(x)\).

Some older or introductory textbooks describe heteroskedasticity as the case where “the variance of \(e\) varies across observations”. This is a poor and confusing definition. It is more constructive to understand that heteroskedasticity means that the conditional variance \(\sigma^{2}(x)\) depends on observables.

Older textbooks also tend to describe homoskedasticity as a component of a correct regression specification and describe heteroskedasticity as an exception or deviance. This description has influenced many generations of economists but it is unfortunately backwards. The correct view is that heteroskedasticity is generic and “standard”, while homoskedasticity is unusual and exceptional. The default in empirical work should be to assume that the errors are heteroskedastic, not the converse.

In apparent contradiction to the above statement we will still frequently impose the homoskedasticity assumption when making theoretical investigations into the properties of estimation and inference methods. The reason is that in many cases homoskedasticity greatly simplifies the theoretical calculations and it is therefore quite advantageous for teaching and learning. It should always be remembered, however, that homoskedasticity is never imposed because it is believed to be a correct feature of an empirical model but rather because of its simplicity.

2.14 Heteroskedastic or Heteroscedastic?

The spelling of the words homoskedastic and heteroskedastic have been somewhat controversial. Early econometrics textbooks were split, with some using a “c” as in heteroscedastic and some ” \(\mathrm{k}\) ” as in heteroskedastic. McCulloch (1985) pointed out that the word is derived from Greek roots.

\ means “to scatter”. Since the proper transliteration of the Greek letter \(\kappa\) in \(\sigma \kappa \varepsilon \delta \alpha v v v \mu \iota\) is ” \(\mathrm{k}\) “, this implies that the correct English spelling of the two words is with a” \(\mathrm{k}\) ” as in homoskedastic and heteroskedastic.

\ means “to scatter”. Since the proper transliteration of the Greek letter \(\kappa\) in \(\sigma \kappa \varepsilon \delta \alpha v v v \mu \iota\) is ” \(\mathrm{k}\) “, this implies that the correct English spelling of the two words is with a” \(\mathrm{k}\) ” as in homoskedastic and heteroskedastic.

2.15 Regression Derivative

One way to interpret the CEF \(m(x)=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X=x]\) is in terms of how marginal changes in the regressors \(X\) imply changes in the conditional expectation of the response variable \(Y\). It is typical to consider marginal changes in a single regressor, say \(X_{1}\), holding the remainder fixed. When a regressor \(X_{1}\) is continuously distributed, we define the marginal effect of a change in \(X_{1}\), holding the variables \(X_{2}, \ldots, X_{k}\) fixed, as the partial derivative of the CEF

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{1}} m\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k}\right) \]

When \(X_{1}\) is discrete we define the marginal effect as a discrete difference. For example, if \(X_{1}\) is binary, then the marginal effect of \(X_{1}\) on the CEF is

\[ m\left(1, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}\right)-m\left(0, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}\right) \]

We can unify the continuous and discrete cases with the notation

\[ \nabla_{1} m(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{cc} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{1}} m\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k}\right), & \text { if } X_{1} \text { is continuous } \\ m\left(1, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}\right)-m\left(0, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}\right), & \text { if } X_{1} \text { is binary. } \end{array}\right. \]

Collecting the \(k\) effects into one \(k \times 1\) vector, we define the regression derivative with respect to \(X\) :

\[ \nabla m(x)=\left[\begin{array}{c} \nabla_{1} m(x) \\ \nabla_{2} m(x) \\ \vdots \\ \nabla_{k} m(x) \end{array}\right] \]

When all elements of \(X\) are continuous, then we have the simplification \(\nabla m(x)=\frac{\partial}{\partial x} m(x)\), the vector of partial derivatives.

There are two important points to remember concerning our definition of the regression derivative. First, the effect of each variable is calculated holding the other variables constant. This is the ceteris paribus concept commonly used in economics. But in the case of a regression derivative, the conditional expectation does not literally hold all else constant. It only holds constant the variables included in the conditional expectation. This means that the regression derivative depends on which regressors are included. For example, in a regression of wages on education, experience, race and gender, the regression derivative with respect to education shows the marginal effect of education on expected wages, holding constant experience, race, and gender. But it does not hold constant an individual’s unobservable characteristics (such as ability), nor variables not included in the regression (such as the quality of education).

Second, the regression derivative is the change in the conditional expectation of \(Y\), not the change in the actual value of \(Y\) for an individual. It is tempting to think of the regression derivative as the change in the actual value of \(Y\), but this is not a correct interpretation. The regression derivative \(\nabla m(x)\) is the change in the actual value of \(Y\) only if the error \(e\) is unaffected by the change in the regressor \(X\). We return to a discussion of causal effects in Section 2.30.

2.16 Linear CEF

An important special case is when the CEF \(m(x)=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X=x]\) is linear in \(x\). In this case we can write the mean equation as

\[ m(x)=x_{1} \beta_{1}+x_{2} \beta_{2}+\cdots+x_{k} \beta_{k}+\beta_{k+1} . \]

Notationally it is convenient to write this as a simple function of the vector \(x\). An easy way to do so is to augment the regressor vector \(X\) by listing the number ” 1 ” as an element. We call this the “constant” and the corresponding coefficient is called the “intercept”. Equivalently, specify that the final element \({ }^{9}\) of the vector \(x\) is \(x_{k}=1\). Thus (2.4) has been redefined as the \(k \times 1\) vector

\[ X=\left(\begin{array}{c} X_{1} \\ X_{2} \\ \vdots \\ X_{k-1} \\ 1 \end{array}\right) \]

With this redefinition, the CEF is

\[ m(x)=x_{1} \beta_{1}+x_{2} \beta_{2}+\cdots+\beta_{k}=x^{\prime} \beta \]

where

\[ \beta=\left(\begin{array}{c} \beta_{1} \\ \vdots \\ \beta_{k} \end{array}\right) \]

is a \(k \times 1\) coefficient vector. This is the linear CEF model. It is also often called the linear regression model, or the regression of \(Y\) on \(X\).

In the linear CEF model the regression derivative is simply the coefficient vector. That is \(\nabla m(x)=\beta\). This is one of the appealing features of the linear CEF model. The coefficients have simple and natural interpretations as the marginal effects of changing one variable, holding the others constant.

\[ \begin{aligned} &\text { Linear CEF Model } \\ &\begin{aligned} Y &=X^{\prime} \beta+e \\ \mathbb{E}[e \mid X] &=0 \end{aligned} \end{aligned} \]

If in addition the error is homoskedastic we call this the homoskedastic linear CEF model.

2.17 Homoskedastic Linear CEF Model

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=X^{\prime} \beta+e \\ \mathbb{E}[e \mid X] &=0 \\ \mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X\right] &=\sigma^{2} \end{aligned} \]

\({ }^{9}\) The order doesn’t matter. It could be any element.

2.18 Linear CEF with Nonlinear Effects

The linear CEF model of the previous section is less restrictive than it might appear, as we can include as regressors nonlinear transformations of the original variables. In this sense, the linear CEF framework is flexible and can capture many nonlinear effects.

For example, suppose we have two scalar variables \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\). The CEF could take the quadratic form

\[ m\left(x_{1}, x_{2}\right)=x_{1} \beta_{1}+x_{2} \beta_{2}+x_{1}^{2} \beta_{3}+x_{2}^{2} \beta_{4}+x_{1} x_{2} \beta_{5}+\beta_{6} . \]

This equation is quadratic in the regressors \(\left(x_{1}, x_{2}\right)\) yet linear in the coefficients \(\beta=\left(\beta_{1}, \ldots, \beta_{6}\right)^{\prime}\). We still call (2.14) a linear CEF because it is a linear function of the coefficients. At the same time, it has nonlinear effects because it is nonlinear in the underlying variables \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{2}\). The key is to understand that (2.14) is quadratic in the variables \(\left(x_{1}, x_{2}\right)\) yet linear in the coefficients \(\beta\).

To simplify the expression we define the transformations \(x_{3}=x_{1}^{2}, x_{4}=x_{2}^{2}, x_{5}=x_{1} x_{2}\), and \(x_{6}=1\), and redefine the regressor vector as \(x=\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{6}\right)^{\prime}\). With this redefinition, \(m\left(x_{1}, x_{2}\right)=x^{\prime} \beta\) which is linear in \(\beta\). For most econometric purposes (estimation and inference on \(\beta\) ) the linearity in \(\beta\) is all that is important.

An exception is in the analysis of regression derivatives. In nonlinear equations such as (2.14) the regression derivative should be defined with respect to the original variables not with respect to the transformed variables. Thus

\[ \begin{aligned} &\frac{\partial}{\partial x_{1}} m\left(x_{1}, x_{2}\right)=\beta_{1}+2 x_{1} \beta_{3}+x_{2} \beta_{5} \\ &\frac{\partial}{\partial x_{2}} m\left(x_{1}, x_{2}\right)=\beta_{2}+2 x_{2} \beta_{4}+x_{1} \beta_{5} . \end{aligned} \]

We see that in the model (2.14), the regression derivatives are not a simple coefficient, but are functions of several coefficients plus the levels of \(\left(x_{1}, x_{2}\right)\). Consequently it is difficult to interpret the coefficients individually. It is more useful to interpret them as a group.

We typically call \(\beta_{5}\) the interaction effect. Notice that it appears in both regression derivative equations and has a symmetric interpretation in each. If \(\beta_{5}>0\) then the regression derivative with respect to \(x_{1}\) is increasing in the level of \(x_{2}\) (and the regression derivative with respect to \(x_{2}\) is increasing in the level of \(x_{1}\) ), while if \(\beta_{5}<0\) the reverse is true.

2.19 Linear CEF with Dummy Variables

When all regressors take a finite set of values it turns out the CEF can be written as a linear function of regressors.

This simplest example is a binary variable which takes only two distinct values. For example, in traditional data sets the variable gender takes only the values man and woman (or male and female). Binary variables are extremely common in econometric applications and are alternatively called dummy variables or indicator variables.

Consider the simple case of a single binary regressor. In this case the conditional expectation can only take two distinct values. For example,

\[ \mathbb{E}[Y \mid \text { gender }]=\left\{\begin{array}{llc} \mu_{0} & \text { if } \quad \text { gender }=\text { man } \\ \mu_{1} & \text { if gender }=\text { woman. } \end{array}\right. \]

To facilitate a mathematical treatment we record dummy variables with the values \(\{0,1\}\). For example

\[ X_{1}=\left\{\begin{array}{llc} 0 & \text { if } & \text { gender }=\text { man } \\ 1 & \text { if } & \text { gender }=\text { woman } . \end{array}\right. \]

Given this notation we write the conditional expectation as a linear function of the dummy variable \(X_{1}\). Thus \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}\right]=\beta_{1} X_{1}+\beta_{2}\) where \(\beta_{1}=\mu_{1}-\mu_{0}\) and \(\beta_{2}=\mu_{0}\). In this simple regression equation the intercept \(\beta_{2}\) is equal to the conditional expectation of \(Y\) for the \(X_{1}=0\) subpopulation (men) and the slope \(\beta_{1}\) is equal to the difference in the conditional expectations between the two subpopulations.

Alternatively, we could have defined \(X_{1}\) as

\[ X_{1}= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } \quad \text { gender }=\text { man } \\ 0 & \text { if } \quad \text { gender }=\text { woman } .\end{cases} \]

In this case, the regression intercept is the expectation for women (rather than for men) and the regression slope has switched signs. The two regressions are equivalent but the interpretation of the coefficients has changed. Therefore it is always important to understand the precise definitions of the variables, and illuminating labels are helpful. For example, labelling \(X_{1}\) as “gender” does not help distinguish between definitions (2.15) and (2.16). Instead, it is better to label \(X_{1}\) as “women” or “female” if definition (2.15) is used, or as “men” or “male” if (2.16) is used.

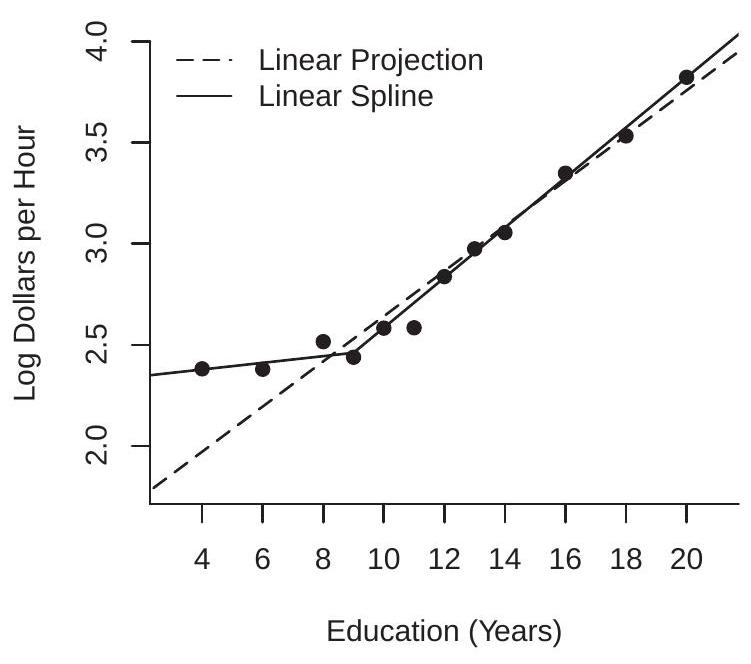

Now suppose we have two dummy variables \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\). For example, \(X_{2}=1\) if the person is married, else \(X_{2}=0\). The conditional expectation given \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) takes at most four possible values:

In this case we can write the conditional mean as a linear function of \(X, X_{2}\) and their product \(X_{1} X_{2}\) :

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}\right]=\beta_{1} X_{1}+\beta_{2} X_{2}+\beta_{3} X_{1} X_{2}+\beta_{4} \]

where \(\beta_{1}=\mu_{10}-\mu_{00}, \beta_{2}=\mu_{01}-\mu_{00}, \beta_{3}=\mu_{11}-\mu_{10}-\mu_{01}+\mu_{00}\), and \(\beta_{4}=\mu_{00}\).

We can view the coefficient \(\beta_{1}\) as the effect of gender on expected log wages for unmarried wage earners, the coefficient \(\beta_{2}\) as the effect of marriage on expected log wages for men wage earners, and the coefficient \(\beta_{3}\) as the difference between the effects of marriage on expected log wages among women and among men. Alternatively, it can also be interpreted as the difference between the effects of gender on expected log wages among married and non-married wage earners. Both interpretations are equally valid. We often describe \(\beta_{3}\) as measuring the interaction between the two dummy variables, or the interaction effect, and describe \(\beta_{3}=0\) as the case when the interaction effect is zero.

In this setting we can see that the CEF is linear in the three variables \(\left(X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{1} X_{2}\right)\). To put the model in the framework of Section \(2.15\) we define the regressor \(X_{3}=X_{1} X_{2}\) and the regressor vector as

\[ X=\left(\begin{array}{c} X_{1} \\ X_{2} \\ X_{3} \\ 1 \end{array}\right) . \]

So while we started with two dummy variables, the number of regressors (including the intercept) is four.

If there are three dummy variables \(X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{3}\), then \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{3}\right]\) takes at most \(2^{3}=8\) distinct values and can be written as the linear function

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{3}\right]=\beta_{1} X_{1}+\beta_{2} X_{2}+\beta_{3} X_{3}+\beta_{4} X_{1} X_{2}+\beta_{5} X_{1} X_{3}+\beta_{6} X_{2} X_{3}+\beta_{7 X 1} X_{2} X_{3}+\beta_{8} \]

which has eight regressors including the intercept. In general, if there are \(p\) dummy variables \(X_{1}, \ldots, X_{p}\) then the CEF \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots, X_{p}\right]\) takes at most \(2^{p}\) distinct values and can be written as a linear function of the \(2^{p}\) regressors including \(X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots, X_{p}\) and all cross-products. A linear regression model which includes all \(2^{p}\) binary interactions is called a saturated dummy variable regression model. It is a complete model of the conditional expectation. In contrast, a model with no interactions equals

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots, X_{p}\right]=\beta_{1} X_{1}+\beta_{2} X_{2}+\cdots+\beta_{p} X_{p}+\beta_{p} . \]

This has \(p+1\) coefficients instead of \(2^{p}\).

We started this section by saying that the conditional expectation is linear whenever all regressors take only a finite number of possible values. How can we see this? Take a categorical variable, such as race. For example, we earlier divided race into three categories. We can record categorical variables using numbers to indicate each category, for example

\[ X_{3}=\left\{\begin{array}{lll} 1 & \text { if } & \text { white } \\ 2 & \text { if } & \text { Black } \\ 3 & \text { if } & \text { other. } \end{array}\right. \]

When doing so, the values of \(X_{3}\) have no meaning in terms of magnitude, they simply indicate the relevant category.

When the regressor is categorical the conditional expectation of \(Y\) given \(X_{3}\) takes a distinct value for each possibility:

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{3}\right]=\left\{\begin{array}{lll} \mu_{1} & \text { if } & X_{3}=1 \\ \mu_{2} & \text { if } & X_{3}=2 \\ \mu_{3} & \text { if } & X_{3}=3 . \end{array}\right. \]

This is not a linear function of \(X_{3}\) itself, but it can be made a linear function by constructing dummy variables for two of the three categories. For example

\[ \begin{aligned} &X_{4}=\left\{\begin{array}{llc} 1 & \text { if } & \text { Black } \\ 0 & \text { if } & \text { not Black } \end{array}\right. \\ &X_{5}=\left\{\begin{array}{lll} 1 & \text { if } & \text { other } \\ 0 & \text { if } & \text { not other. } \end{array}\right. \end{aligned} \]

In this case, the categorical variable \(X_{3}\) is equivalent to the pair of dummy variables \(\left(X_{4}, X_{5}\right)\). The explicit relationship is

\[ X_{3}=\left\{\begin{array}{lll} 1 & \text { if } & X_{4}=0 \text { and } X_{5}=0 \\ 2 & \text { if } & X_{4}=1 \text { and } X_{5}=0 \\ 3 & \text { if } & X_{4}=0 \text { and } X_{5}=1 \end{array}\right. \]

Given these transformations, we can write the conditional expectation of \(Y\) as a linear function of \(X_{4}\) and \(X_{5}\)

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{3}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{4}, X_{5}\right]=\beta_{1} X_{4}+\beta_{2} X_{5}+\beta_{3} . \]

We can write the CEF as either \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{3}\right]\) or \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y \mid X_{4}, X_{5}\right]\) (they are equivalent), but it is only linear as a function of \(X_{4}\) and \(X_{5}\).

This setting is similar to the case of two dummy variables, with the difference that we have not included the interaction term \(X_{4} X_{5}\). This is because the event \(\left\{X_{4}=1\right.\) and \(\left.X_{5}=1\right\}\) is empty by construction, so \(X_{4} X_{5}=0\) by definition.

2.20 Best Linear Predictor

While the conditional expectation \(m(X)=\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\) is the best predictor of \(Y\) among all functions of \(X\), its functional form is typically unknown. In particular, the linear CEF model is empirically unlikely to be accurate unless \(X\) is discrete and low-dimensional so all interactions are included. Consequently, in most cases it is more realistic to view the linear specification (2.13) as an approximation. In this section we derive a specific approximation with a simple interpretation.

Theorem \(2.7\) showed that the conditional expectation \(m(X)\) is the best predictor in the sense that it has the lowest mean squared error among all predictors. By extension, we can define an approximation to the CEF by the linear function with the lowest mean squared error among all linear predictors.

For this derivation we require the following regularity condition.

Assumption \(2.1\)

- \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty\)

- \(\mathbb{E}\|X\|^{2}<\infty\)

- \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}=\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\) is positive definite.

In Assumption 2.1.2 we use \(\|x\|=\left(x^{\prime} x\right)^{1 / 2}\) to denote the Euclidean length of the vector \(x\).

The first two parts of Assumption \(2.1\) imply that the variables \(Y\) and \(X\) have finite means, variances, and covariances. The third part of the assumption is more technical, and its role will become apparent shortly. It is equivalent to imposing that the columns of the matrix \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}=\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\) are linearly independent and that the matrix is invertible.

A linear predictor for \(Y\) is a function \(X^{\prime} \beta\) for some \(\beta \in \mathbb{R}^{k}\). The mean squared prediction error is

\[ S(\beta)=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(Y-X^{\prime} \beta\right)^{2}\right] . \]

The best linear predictor of \(Y\) given \(X\), written \(\mathscr{P}[Y \mid X]\), is found by selecting the \(\beta\) which minimizes \(S(\beta)\).

Definition 2.5 The Best Linear Predictor of \(Y\) given \(X\) is

\[ \mathscr{P}[Y \mid X]=X^{\prime} \beta \]

where \(\beta\) minimizes the mean squared prediction error

\[ S(\beta)=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(Y-X^{\prime} \beta\right)^{2}\right] . \]

The minimizer

\[ \beta=\underset{b \in \mathbb{R}^{k}}{\operatorname{argmin}} S(b) \]

is called the Linear Projection Coefficient. We now calculate an explicit expression for its value. The mean squared prediction error (2.17) can be written out as a quadratic function of \(\beta\) :

\[ S(\beta)=\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]-2 \beta^{\prime} \mathbb{E}[X Y]+\beta^{\prime} \mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right] \beta . \]

The quadratic structure of \(S(\beta)\) means that we can solve explicitly for the minimizer. The first-order condition for minimization (from Appendix A.20) is

\[ 0=\frac{\partial}{\partial \beta} S(\beta)=-2 \mathbb{E}[X Y]+2 \mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right] \beta . \]

Rewriting \((2.20)\) as

\[ 2 \mathbb{E}[X Y]=2 \mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right] \beta \]

and dividing by 2 , this equation takes the form

\[ \boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y}=\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X} \beta \]

where \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y}=\mathbb{E}[X Y]\) is \(k \times 1\) and \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}=\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\) is \(k \times k\). The solution is found by inverting the matrix \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\), and is written

\[ \beta=\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y} \]

or

\[ \beta=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y] . \]

It is worth taking the time to understand the notation involved in the expression (2.22). \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\) is a \(k \times k\) matrix and \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y}\) is a \(k \times 1\) column vector. Therefore, alternative expressions such as \(\frac{\mathbb{E}[X Y]}{\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]}\) or \(\mathbb{E}[X Y]\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1}\) are incoherent and incorrect. We also can now see the role of Assumption 2.1.3. It is equivalent to assuming that \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\) has an inverse \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}^{-1}\) which is necessary for the solution to the normal equations (2.21) to be unique, and equivalently for \((2.22)\) to be uniquely defined. In the absence of Assumption \(2.1 .3\) there could be multiple solutions to the equation (2.21).

We now have an explicit expression for the best linear predictor:

\[ \mathscr{P}[Y \mid X]=X^{\prime}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y] . \]

This expression is also referred to as the linear projection of \(Y\) on \(X\).

The projection error is

\[ e=Y-X^{\prime} \beta . \]

This equals the error (2.9) from the regression equation when (and only when) the conditional expectation is linear in \(X\), otherwise they are distinct.

Rewriting, we obtain a decomposition of \(Y\) into linear predictor and error

\[ Y=X^{\prime} \beta+e . \]

In general, we call equation (2.24) or \(X^{\prime} \beta\) the best linear predictor of \(Y\) given \(X\), or the linear projection of \(Y\) on \(X\). Equation (2.24) is also often called the regression of \(Y\) on \(X\) but this can sometimes be confusing as economists use the term “regression” in many contexts. (Recall that we said in Section \(2.15\) that the linear CEF model is also called the linear regression model.)

An important property of the projection error \(e\) is

\[ \mathbb{E}[X e]=0 . \]

To see this, using the definitions (2.23) and (2.22) and the matrix properties \(\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{A}^{-1}=\boldsymbol{I}\) and \(\boldsymbol{I} \boldsymbol{a}=\boldsymbol{a}\),

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[X e] &=\mathbb{E}\left[X\left(Y-X^{\prime} \beta\right)\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}[X Y]-\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y] \\ &=0 \end{aligned} \]

as claimed.

Equation (2.25) is a set of \(k\) equations, one for each regressor. In other words, (2.25) is equivalent to

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[X_{j} e\right]=0 \]

for \(j=1, \ldots, k\). As in (2.12), the regressor vector \(X\) typically contains a constant, e.g. \(X_{k}=1\). In this case (2.27) for \(j=k\) is the same as

\[ \mathbb{E}[e]=0 . \]

Thus the projection error has a mean of zero when the regressor vector contains a constant. (When \(X\) does not have a constant (2.28) is not guaranteed. As it is desirable for \(e\) to have a zero mean this is a good reason to always include a constant in any regression model.)

It is also useful to observe that because \(\operatorname{cov}\left(X_{j}, e\right)=\mathbb{E}\left[X_{j} e\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[X_{j}\right] \mathbb{E}[e]\), then (2.27)-(2.28) together imply that the variables \(X_{j}\) and \(e\) are uncorrelated.

This completes the derivation of the model. We summarize some of the most important properties.

Theorem 2.9 Properties of Linear Projection Model Under Assumption 2.1,

The moments \(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\) and \(\mathbb{E}[X Y]\) exist with finite elements.

The linear projection coefficient (2.18) exists, is unique, and equals

\[ \beta=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y] . \]

1. The best linear predictor of \(Y\) given \(X\) is

\[ \mathscr{P}(Y \mid X)=X^{\prime}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y] . \]

1. The projection error \(e=Y-X^{\prime} \beta\) exists. It satisfies \(\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right]<\infty\) and \(\mathbb{E}[X e]=0\).

If \(X\) contains an constant, then \(\mathbb{E}[e]=0\).

If \(\mathbb{E}|Y|^{r}<\infty\) and \(\mathbb{E}\|X\|^{r}<\infty\) for \(r \geq 2\) then \(\mathbb{E}|e|^{r}<\infty\).

A complete proof of Theorem \(2.9\) is given in Section 2.33.

It is useful to reflect on the generality of Theorem 2.9. The only restriction is Assumption 2.1. Thus for any random variables \((Y, X)\) with finite variances we can define a linear equation (2.24) with the properties listed in Theorem 2.9. Stronger assumptions (such as the linear CEF model) are not necessary. In this sense the linear model (2.24) exists quite generally. However, it is important not to misinterpret the generality of this statement. The linear equation (2.24) is defined as the best linear predictor. It is not necessarily a conditional mean, nor a parameter of a structural or causal economic model. Linear Projection Model

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=X^{\prime} \beta+e \\ \mathbb{E}[X e] &=0 \\ \beta &=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y] \end{aligned} \]

2.21 Invertibility and Identification

The linear projection coefficient \(\beta=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y]\) exists and is unique as long as the \(k \times k\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}=\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\) is invertible. The matrix \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\) is often called the design matrix as in experimental settings the researcher is able to control \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\) by manipulating the distribution of the regressors \(X\).

Observe that for any non-zero \(\alpha \in \mathbb{R}^{k}\),

\[ \alpha^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X} \alpha=\mathbb{E}\left[\alpha^{\prime} X X^{\prime} \alpha\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\alpha^{\prime} X\right)^{2}\right] \geq 0 \]

so \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\) by construction is positive semi-definite, conventionally written as \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X} \geq 0\). The assumption that it is positive definite means that this is a strict inequality, \(\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\alpha^{\prime} X\right)^{2}\right]>0\). This is conventionally written as \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}>0\). This condition means that there is no non-zero vector \(\alpha\) such that \(\alpha^{\prime} X=0\) identically. Positive definite matrices are invertible. Thus when \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}>0\) then \(\beta=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[X Y]\) exists and is uniquely defined. In other words, if we can exclude the possibility that a linear function of \(X\) is degenerate, then \(\beta\) is uniquely defined.

Theorem \(2.5\) shows that the linear projection coefficient \(\beta\) is identified (uniquely determined) under Assumption 2.1. The key is invertibility of \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\). Otherwise, there is no unique solution to the equation

\[ \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X} \beta=\boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y} . \]

When \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}\) is not invertible there are multiple solutions to (2.29). In this case the coefficient \(\beta\) is not identified as it does not have a unique value.

2.22 Minimization

The mean squared prediction error (2.19) is a function with vector argument of the form

\[ f(x)=a-2 b^{\prime} x+x^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C} x \]

where \(\boldsymbol{C}>0\). For any function of this form, the unique minimizer is

\[ x=\boldsymbol{C}^{-1} b . \]

To see that this is the unique minimizer we present two proofs. The first uses matrix calculus. From Appendix A.20

\[ \begin{gathered} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(b^{\prime} x\right)=b \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(x^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C} x\right)=2 \boldsymbol{C} x \\ \frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial x \partial x^{\prime}}\left(x^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C} x\right)=2 \boldsymbol{C} . \end{gathered} \]

Using (2.31) and (2.32), we find

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} f(x)=-2 b+2 \boldsymbol{C} x . \]

The first-order condition for minimization sets this derivative equal to zero. Thus the solution satisfies \(-2 b+2 \boldsymbol{C} x=0\). Solving for \(x\) we find (2.30). Using (2.33) we also find

\[ \frac{\partial^{2}}{\partial x \partial x^{\prime}} f(x)=2 \boldsymbol{C}>0 \]

which is the second-order condition for minimization. This shows that (2.30) is the unique minimizer of \(f(x)\).

Our second proof is algebraic. Re-write \(f(x)\) as

\[ f(x)=\left(a-b^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C}^{-1} b\right)+\left(x-\boldsymbol{C}^{-1} b\right)^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C}\left(x-\boldsymbol{C}^{-1} b\right) . \]

The first term does not depend on \(x\) so does not affect the minimizer. The second term is a quadratic form in a positive definite matrix. This means that for any non-zero \(\alpha, \alpha^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C} \alpha>0\). Thus for \(x \neq C^{-1} b\), the second-term is strictly positive, yet for \(x=C^{-1} b\) this term equals zero. It is therefore minimized at \(x=C^{-1} b\) as claimed.

2.23 Illustrations of Best Linear Predictor

We illustrate the best linear predictor (projection) using three log wage equations introduced in earlier sections.

For our first example, we consider a model with the two dummy variables for gender and race similar to Table 2.1. As we learned in Section 2.17, the entries in this table can be equivalently expressed by a linear CEF. For simplicity, let’s consider the CEF of \(\log (\) wage \()\) as a function of Black and female.

\[ \mathbb{E}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { Black, female }]=-0.20 \text { Black }-0.24 \text { female }+0.10 \text { Black } \times \text { female }+3.06 \text {. } \]

This is a CEF as the variables are binary and all interactions are included.

Now consider a simpler model omitting the interaction effect. This is the linear projection on the variables Black and female

\[ \mathscr{P}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { Black, female }]=-0.15 \text { Black }-0.23 \text { female }+3.06 . \]

What is the difference? The full CEF (2.34) shows that the race gap is differentiated by gender: it is \(20 %\) for Black men (relative to non-Black men) and \(10 %\) for Black women (relative to non-Black women). The projection model (2.35) simplifies this analysis, calculating an average \(15 %\) wage gap for Black wage earners, ignoring the role of gender. Notice that this is despite the fact that gender is included in (2.35).

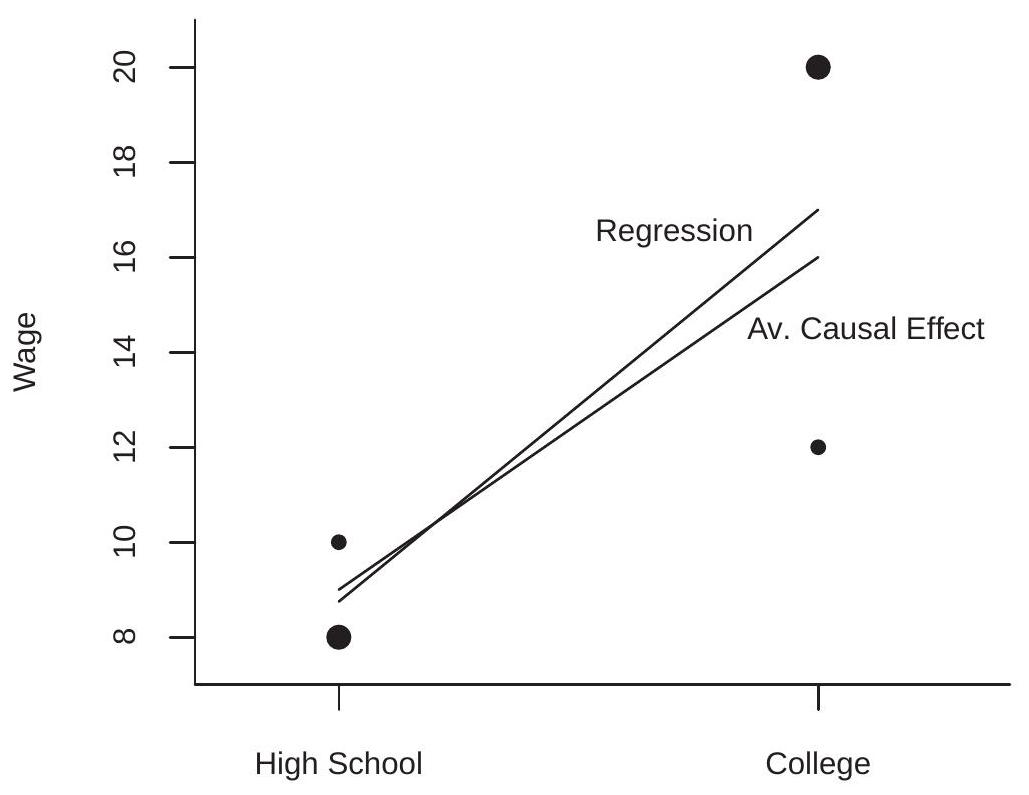

- Projections onto Education

.jpg)

- Projections onto Experience

Figure 2.6: Projections of Log Wage onto Education and Experience

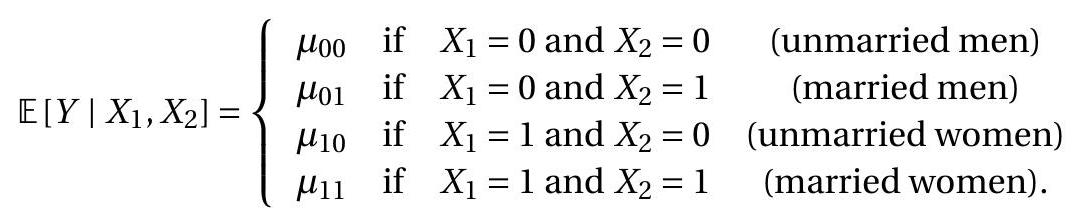

For our second example we consider the CEF of log wages as a function of years of education for white men which was illustrated in Figure \(2.3\) and is repeated in Figure 2.6(a). Superimposed on the figure are two projections. The first (given by the dashed line) is the linear projection of log wages on years of education

\[ \mathscr{P}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { education }]=0.11 \text { education }+1.5 \text {. } \]

This simple equation indicates an average \(11 %\) increase in wages for every year of education. An inspection of the Figure shows that this approximation works well for education \(\geq 9\), but under-predicts for individuals with lower levels of education. To correct this imbalance we use a linear spline equation which allows different rates of return above and below 9 years of education:

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathscr{P}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { education, }(\text { education }-9) \times \mathbb{1} \text { education }>9\}] \\ &=0.02 \text { education }+0.10 \times(\text { education }-9) \times \mathbb{1} \text { education }>9\}+2.3 . \end{aligned} \]

This equation is displayed in Figure 2.6(a) using the solid line, and appears to fit much better. It indicates a \(2 %\) increase in mean wages for every year of education below 9 , and a \(12 %\) increase in mean wages for every year of education above 9 . It is still an approximation to the conditional mean but it appears to be fairly reasonable.

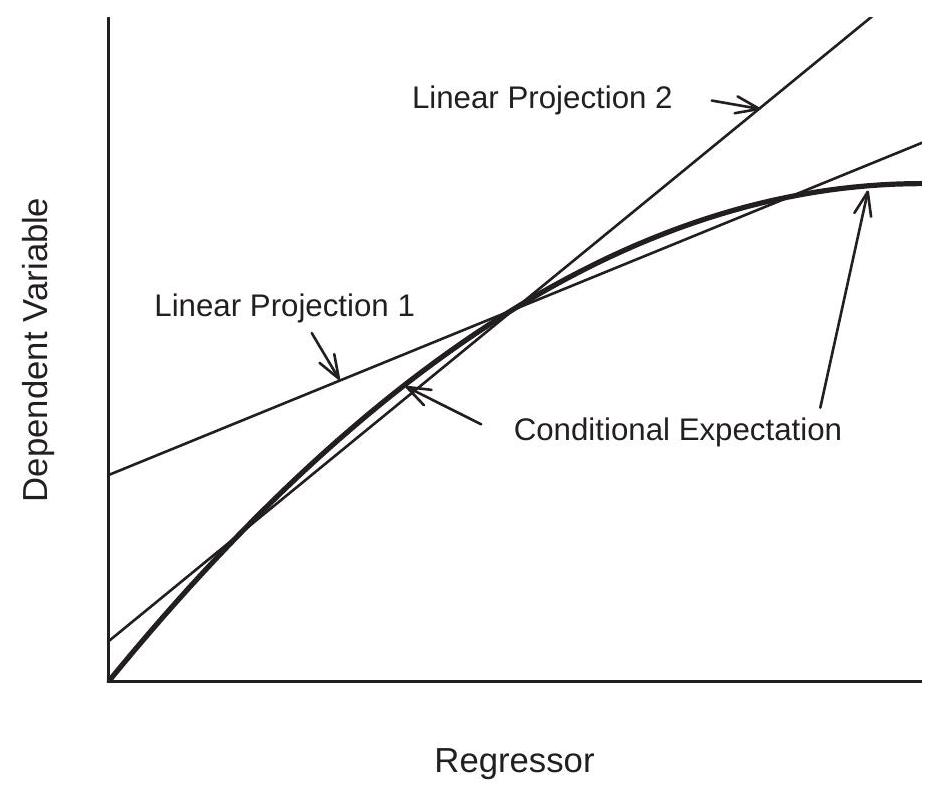

For our third example we take the CEF of log wages as a function of years of experience for white men with 12 years of education, which was illustrated in Figure \(2.4\) and is repeated as the solid line in Figure 2.6(b). Superimposed on the figure are two projections. The first (given by the dot-dashed line) is the linear projection on experience

\[ \mathscr{P}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { experience }]=0.011 \text { experience }+2.5 \]

and the second (given by the dashed line) is the linear projection on experience and its square

\[ \mathscr{P}[\log (\text { wage }) \mid \text { experience }]=0.046 \text { experience }-0.0007 \text { experience }^{2}+2.3 \text {. } \]

It is fairly clear from an examination of Figure \(2.6(\mathrm{~b})\) that the first linear projection is a poor approximation. It over-predicts wages for young and old workers, under-predicts for the rest, and misses the strong downturn in expected wages for older wage-earners. The second projection fits much better. We can call this equation a quadratic projection because the function is quadratic in experience.

2.24 Linear Predictor Error Variance

As in the CEF model, we define the error variance as \(\sigma^{2}=\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right]\). Setting \(Q_{Y Y}=\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]\) and \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{Y X}=\) \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y X^{\prime}\right]\) we can write \(\sigma^{2}\) as

\[ \begin{aligned} \sigma^{2} &=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(Y-X^{\prime} \beta\right)^{2}\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]-2 \mathbb{E}\left[Y X^{\prime}\right] \beta+\beta^{\prime} \mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right] \beta \\ &=Q_{Y Y}-2 \boldsymbol{Q}_{Y X} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y}+\boldsymbol{Q}_{Y X} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y} \\ &=Q_{Y Y}-\boldsymbol{Q}_{Y X} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y} \\ & \stackrel{\text { def }}{=} Q_{Y Y \cdot X} . \end{aligned} \]

One useful feature of this formula is that it shows that \(Q_{Y Y \cdot X}=Q_{Y Y}-\boldsymbol{Q}_{Y X} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q}_{X Y}\) equals the variance of the error from the linear projection of \(Y\) on \(X\).

2.25 Regression Coefficients

Sometimes it is useful to separate the constant from the other regressors and write the linear projection equation in the format

\[ Y=X^{\prime} \beta+\alpha+e \]

where \(\alpha\) is the intercept and \(X\) does not contain a constant.

Taking expectations of this equation, we find

\[ \mathbb{E}[Y]=\mathbb{E}\left[X^{\prime} \beta\right]+\mathbb{E}[\alpha]+\mathbb{E}[e] \]

or \(\mu_{Y}=\mu_{X}^{\prime} \beta+\alpha\) where \(\mu_{Y}=\mathbb{E}[Y]\) and \(\mu_{X}=\mathbb{E}[X]\), since \(\mathbb{E}[e]=0\) from (2.28). (While \(X\) does not contain a constant, the equation does so (2.28) still applies.) Rearranging, we find \(\alpha=\mu_{Y}-\mu_{X}^{\prime} \beta\). Subtracting this equation from (2.37) we find

\[ Y-\mu_{Y}=\left(X-\mu_{X}\right)^{\prime} \beta+e, \]

a linear equation between the centered variables \(Y-\mu_{Y}\) and \(X-\mu_{X}\). (They are centered at their means so are mean-zero random variables.) Because \(X-\mu_{X}\) is uncorrelated with \(e\), (2.38) is also a linear projection. Thus by the formula for the linear projection model,