Chapter 4: Least Squares Regression

4 Least Squares Regression

4.1 Introduction

In this chapter we investigate some finite-sample properties of the least squares estimator in the linear regression model. In particular we calculate its finite-sample expectation and covariance matrix and propose standard errors for the coefficient estimators.

4.2 Random Sampling

Assumption \(3.1\) specified that the observations have identical distributions. To derive the finitesample properties of the estimators we will need to additionally specify the dependence structure across the observations.

The simplest context is when the observations are mutually independent in which case we say that they are independent and identically distributed or i.i.d. It is also common to describe i.i.d. observations as a random sample. Traditionally, random sampling has been the default assumption in crosssection (e.g. survey) contexts. It is quite convenient as i.i.d. sampling leads to straightforward expressions for estimation variance. The assumption seems appropriate (meaning that it should be approximately valid) when samples are small and relatively dispersed. That is, if you randomly sample 1000 people from a large country such as the United States it seems reasonable to model their responses as mutually independent.

Assumption 4.1 The random variables \(\left\{\left(Y_{1}, X_{1}\right), \ldots,\left(Y_{i}, X_{i}\right), \ldots,\left(Y_{n}, X_{n}\right)\right\}\) are independent and identically distributed.

For most of this chapter we will use Assumption \(4.1\) to derive properties of the OLS estimator.

Assumption \(4.1\) means that if you take any two individuals \(i \neq j\) in a sample, the values \(\left(Y_{i}, X_{i}\right)\) are independent of the values \(\left(Y_{j}, X_{j}\right)\) yet have the same distribution. Independence means that the decisions and choices of individual \(i\) do not affect the decisions of individual \(j\) and conversely.

This assumption may be violated if individuals in the sample are connected in some way, for example if they are neighbors, members of the same village, classmates at a school, or even firms within a specific industry. In this case it seems plausible that decisions may be inter-connected and thus mutually dependent rather than independent. Allowing for such interactions complicates inference and requires specialized treatment. A currently popular approach which allows for mutual dependence is known as clustered dependence which assumes that that observations are grouped into “clusters” (for example, schools). We will discuss clustering in more detail in Section 4.21.

4.3 Sample Mean

We start with the simplest setting of the intercept-only model

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=\mu+e \\ \mathbb{E}[e] &=0 . \end{aligned} \]

which is equivalent to the regression model with \(k=1\) and \(X=1\). In the intercept model \(\mu=\mathbb{E}[Y]\) is the expectation of \(Y\). (See Exercise 2.15.) The least squares estimator \(\widehat{\mu}=\bar{Y}\) equals the sample mean as shown in equation (3.8).

We now calculate the expectation and variance of the estimator \(\bar{Y}\). Since the sample mean is a linear function of the observations its expectation is simple to calculate

\[ \mathbb{E}[\bar{Y}]=\mathbb{E}\left[\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} Y_{i}\right]=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}\right]=\mu . \]

This shows that the expected value of the least squares estimator (the sample mean) equals the projection coefficient (the population expectation). An estimator with the property that its expectation equals the parameter it is estimating is called unbiased.

Definition \(4.1\) An estimator \(\widehat{\theta}\) for \(\theta\) is unbiased if \(\mathbb{E}[\widehat{\theta}]=\theta\)

We next calculate the variance of the estimator \(\bar{Y}\) under Assumption 4.1. Making the substitution \(Y_{i}=\mu+e_{i}\) we find

\[ \bar{Y}-\mu=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} e_{i} . \]

Then

\[ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{var}[\bar{Y}] &=\mathbb{E}\left[(\bar{Y}-\mu)^{2}\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} e_{i}\right)\left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} e_{j}\right)\right] \\ &=\frac{1}{n^{2}} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} \mathbb{E}\left[e_{i} e_{j}\right] \\ &=\frac{1}{n^{2}} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sigma^{2} \\ &=\frac{1}{n} \sigma^{2} . \end{aligned} \]

The second-to-last inequality is because \(\mathbb{E}\left[e_{i} e_{j}\right]=\sigma^{2}\) for \(i=j\) yet \(\mathbb{E}\left[e_{i} e_{j}\right]=0\) for \(i \neq j\) due to independence.

We have shown that \(\operatorname{var}[\bar{Y}]=\frac{1}{n} \sigma^{2}\). This is the familiar formula for the variance of the sample mean.

4.4 Linear Regression Model

We now consider the linear regression model. Throughout this chapter we maintain the following.

Assumption 4.2 Linear Regression Model The variables \((Y, X)\) satisfy the linear regression equation

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &=X^{\prime} \beta+e \\ \mathbb{E}[e \mid X] &=0 . \end{aligned} \]

The variables have finite second moments

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathbb{E}\left[Y^{2}\right]<\infty \\ &\mathbb{E}\|X\|^{2}<\infty \end{aligned} \]

and an invertible design matrix

\[ \boldsymbol{Q}_{X X}=\mathbb{E}\left[X X^{\prime}\right]>0 . \]

We will consider both the general case of heteroskedastic regression where the conditional variance \(\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X\right]=\sigma^{2}(X)\) is unrestricted, and the specialized case of homoskedastic regression where the conditional variance is constant. In the latter case we add the following assumption.

Assumption 4.3 Homoskedastic Linear Regression Model In addition to Assumption \(4.2\)

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X\right]=\sigma^{2}(X)=\sigma^{2} \]

is independent of \(X\).

4.5 Expectation of Least Squares Estimator

In this section we show that the OLS estimator is unbiased in the linear regression model. This calculation can be done using either summation notation or matrix notation. We will use both.

First take summation notation. Observe that under (4.1)-(4.2)

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} \mid X_{1}, \ldots, X_{n}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} \mid X_{i}\right]=X_{i}^{\prime} \beta . \]

The first equality states that the conditional expectation of \(Y_{i}\) given \(\left\{X_{1}, \ldots, X_{n}\right\}\) only depends on \(X_{i}\) because the observations are independent across \(i\). The second equality is the assumption of a linear conditional expectation. Using definition (3.11), the conditioning theorem (Theorem 2.3), the linearity of expectations, (4.4), and properties of the matrix inverse,

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\beta} \mid X_{1}, \ldots, X_{n}\right] &=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} Y_{i}\right) \mid X_{1}, \ldots, X_{n}\right] \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} Y_{i}\right) \mid X_{1}, \ldots, X_{n}\right] \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathbb{E}\left[X_{i} Y_{i} \mid X_{1}, \ldots, X_{n}\right] \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} \mid X_{i}\right] \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \beta \\ &=\beta . \end{aligned} \]

Now let’s show the same result using matrix notation. (4.4) implies

\[ \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{Y} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\left(\begin{array}{c} \vdots \\ \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \\ \vdots \end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{c} \vdots \\ X_{i}^{\prime} \beta \\ \vdots \end{array}\right)=\boldsymbol{X} \beta . \]

Similarly

\[ \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\left(\begin{array}{c} \vdots \\ \mathbb{E}\left[e_{i} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \\ \vdots \end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{c} \vdots \\ \mathbb{E}\left[e_{i} \mid X_{i}\right] \\ \vdots \end{array}\right)=0 . \]

Using \(\widehat{\beta}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}\right)\), the conditioning theorem, the linearity of expectations, (4.5), and the properties of the matrix inverse,

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] &=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{Y} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X} \beta \\ &=\beta . \end{aligned} \]

At the risk of belaboring the derivation, another way to calculate the same result is as follows. Insert \(\boldsymbol{Y}=\boldsymbol{X} \beta+\boldsymbol{e}\) into the formula for \(\widehat{\beta}\) to obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\beta} &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime}(\boldsymbol{X} \beta+\boldsymbol{e})\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X} \beta+\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{e}\right) \\ &=\beta+\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{e} . \end{aligned} \]

This is a useful linear decomposition of the estimator \(\widehat{\beta}\) into the true parameter \(\beta\) and the stochastic component \(\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{e}\). Once again, we can calculate that

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta}-\beta \mid \boldsymbol{X}] &=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=0 . \end{aligned} \]

Regardless of the method we have shown that \(\mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\beta\). We have shown the following theorem.

Theorem 4.1 Expectation of Least Squares Estimator In the linear regression model (Assumption 4.2) with i.i.d. sampling (Assumption 4.1)

\[ \mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\beta . \]

Equation (4.7) says that the estimator \(\widehat{\beta}\) is unbiased for \(\beta\), conditional on \(\boldsymbol{X}\). This means that the conditional distribution of \(\widehat{\beta}\) is centered at \(\beta\). By “conditional on \(X\)” this means that the distribution is unbiased for any realization of the regressor matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\). In conditional models we simply refer to this as saying \(" \widehat{\beta}\) is unbiased for \(\beta\) “.

It is worth mentioning that Theorem 4.1, and all finite sample results in this chapter, make the implicit assumption that \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\) is full rank with probability one.

4.6 Variance of Least Squares Estimator

In this section we calculate the conditional variance of the OLS estimator.

For any \(r \times 1\) random vector \(Z\) define the \(r \times r\) covariance matrix

\[ \operatorname{var}[Z]=\mathbb{E}\left[(Z-\mathbb{E}[Z])(Z-\mathbb{E}[Z])^{\prime}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[Z Z^{\prime}\right]-(\mathbb{E}[Z])(\mathbb{E}[Z])^{\prime} \]

and for any pair \((Z, X)\) define the conditional covariance matrix

\[ \operatorname{var}[Z \mid X]=\mathbb{E}\left[(Z-\mathbb{E}[Z \mid X])(Z-\mathbb{E}[Z \mid X])^{\prime} \mid X\right] . \]

We define \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} \stackrel{\text { def }}{=} \operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]\) as the conditional covariance matrix of the regression coefficient estimators. We now derive its form.

The conditional covariance matrix of the \(n \times 1\) regression error \(\boldsymbol{e}\) is the \(n \times n\) matrix

\[ \operatorname{var}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{e} \boldsymbol{e}^{\prime} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \stackrel{\text { def }}{=} \boldsymbol{D} . \]

The \(i^{t h}\) diagonal element of \(\boldsymbol{D}\) is

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[e_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[e_{i}^{2} \mid X_{i}\right]=\sigma_{i}^{2} \]

while the \(i j^{t h}\) off-diagonal element of \(\boldsymbol{D}\) is

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[e_{i} e_{j} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left(e_{i} \mid X_{i}\right) \mathbb{E}\left[e_{j} \mid X_{j}\right]=0 \]

where the first equality uses independence of the observations (Assumption 4.1) and the second is (4.2). Thus \(\boldsymbol{D}\) is a diagonal matrix with \(i^{t h}\) diagonal element \(\sigma_{i}^{2}\) :

\[ \boldsymbol{D}=\operatorname{diag}\left(\sigma_{1}^{2}, \ldots, \sigma_{n}^{2}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{cccc} \sigma_{1}^{2} & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \sigma_{2}^{2} & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & \sigma_{n}^{2} \end{array}\right) \]

In the special case of the linear homoskedastic regression model (4.3), then \(\mathbb{E}\left[e_{i}^{2} \mid X_{i}\right]=\sigma_{i}^{2}=\sigma^{2}\) and we have the simplification \(\boldsymbol{D}=\boldsymbol{I}_{n} \sigma^{2}\). In general, however, \(\boldsymbol{D}\) need not necessarily take this simplified form.

For any \(n \times r\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}=\boldsymbol{A}(\boldsymbol{X})\),

\[ \operatorname{var}\left[\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\operatorname{var}\left[\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{A} . \]

In particular, we can write \(\widehat{\beta}=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}\) where \(\boldsymbol{A}=\boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\) and thus

\[ \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{A}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} . \]

It is useful to note that

\[ \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \sigma_{i}^{2}, \]

a weighted version of \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\).

In the special case of the linear homoskedastic regression model, \(\boldsymbol{D}=\boldsymbol{I}_{n} \sigma^{2}\), so \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}=\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X} \sigma^{2}\), and the covariance matrix simplifies to \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2}\).

Theorem 4.2 Variance of Least Squares Estimator In the linear regression model (Assumption 4.2) with i.i.d. sampling (Assumption 4.1)

\[ \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \]

where \(\boldsymbol{D}\) is defined in (4.8). If in addition the error is homoskedastic (Assumption 4.3) then (4.10) simplifies to \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\).

4.7 Unconditional Moments

The previous sections derived the form of the conditional expectation and variance of the least squares estimator where we conditioned on the regressor matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\). What about the unconditional expectation and variance?

Indeed, it is not obvious if \(\widehat{\beta}\) has a finite expectation or variance. Take the case of a single dummy variable regressor \(D_{i}\) with no intercept. Assume \(\mathbb{P}\left[D_{i}=1\right]=p<1\). Then

\[ \widehat{\beta}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} D_{i} Y_{i}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} D_{i}} \]

is well defined if \(\sum_{i=1}^{n} D_{i}>0\). However, \(\mathbb{P}\left[\sum_{i=1}^{n} D_{i}=0\right]=(1-p)^{n}>0\). This means that with positive (but small) probability \(\widehat{\beta}\) does not exist. Consequently \(\widehat{\beta}\) has no finite moments! We ignore this complication in practice but it does pose a conundrum for theory. This existence problem arises whenever there are discrete regressors.

This dilemma is avoided when the regressors have continuous distributions. A clean statement was obtained by Kinal (1980) under the assumption of normal regressors and errors. Theorem 4.3 Kinal (1980)

In the linear regression model with i.i.d. sampling, if in addition \((X, e)\) have a joint normal distribution, then for any \(r, \mathbb{E}\|\widehat{\beta}\|^{r}<\infty\) if and only if \(r<n-k+1\).

This shows that when the errors and regressors are normally distributed that the least squares estimator possesses all moments up to \(n-k\) which includes all moments of practical interest. The normality assumption is not critical for this result. What is key is the assumption that the regressors are continuously distributed.

The law of iterated expectations (Theorem 2.1) combined with Theorems \(4.1\) and \(4.3\) allow us to deduce that the least squares estimator is unconditionally unbiased. Under the normality assumption Theorem \(4.3\) allows us to apply the law of iterated expectations, and thus using Theorems \(4.1\) we deduce that if \(n>k\)

\[ \mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta}]=\mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]]=\beta . \]

Hence \(\widehat{\beta}\) is unconditionally unbiased as asserted.

Furthermore, if \(n-k>1\) then \(\mathbb{E}\|\widehat{\beta}\|^{2}<\infty\) and \(\widehat{\beta}\) has a finite unconditional variance. Using Theorem \(2.8\) we can calculate explicitly that

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta}]=\mathbb{E}[\operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]]+\operatorname{var}[\mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]]=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\right] \]

the second equality because \(\mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\beta\) has zero variance. In the homoskedastic case this simplifies to

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta}]=\sigma^{2} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\right] . \]

In both cases the expectation cannot pass through the matrix inverse because this is a nonlinear function. Thus there is not a simple expression for the unconditional variance, other than stating that is it the expectation of the conditional variance.

4.8 Gauss-Markov Theorem

The Gauss-Markov Theorem is one of the most celebrated results in econometric theory. It provides a classical justification for the least squares estimator, showing that it is lowest variance among unbiased estimators.

Write the homoskedastic linear regression model in vector format as

\[ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{Y} &=\boldsymbol{X} \beta+\boldsymbol{e} \\ \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] &=0 \\ \operatorname{var}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] &=\boldsymbol{I}_{n} \sigma^{2} . \end{aligned} \]

In this model we know that the least squares estimator is unbiased for \(\beta\) and has covariance matrix \(\sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\). The question raised in this section is if there exists an alternative unbiased estimator \(\widetilde{\beta}\) which has a smaller covariance matrix.

The following version of the theorem is due to B. E. Hansen (2021).

Theorem 4.4 Gauss-Markov Take the homoskedastic linear regression model (4.11)-(4.13). If \(\widetilde{\beta}\) is an unbiased estimator of \(\beta\) then

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widetilde{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] \geq \sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \]

Theorem \(4.4\) provides a lower bound on the covariance matrix of unbiased estimators under the assumption of homoskedasticity. It says that no unbiased estimator can have a variance matrix smaller (in the positive definite sense) than \(\sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\). Since the variance of the OLS estimator is exactly equal to this bound this means that no unbiased estimator has a lower variance than OLS. Consequently we describe OLS as efficient in the class of unbiased estimators.

This earliest version of Theorem \(4.4\) was articulated by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1823. Andreı̆ Andreevich Markov provided a textbook treatment of the theorem in 1912, and clarified the central role of unbiasedness, which Gauss had only assumed implicitly.

Their versions of the Theorem restricted attention to linear estimators of \(\beta\), which are estimators that can be written as \(\widetilde{\beta}=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}\), where \(\boldsymbol{A}=\boldsymbol{A}(\boldsymbol{X})\) is an \(m \times n\) function of the regressors \(\boldsymbol{X}\). Linearity in this context means “linear in \(\boldsymbol{Y}\)”. This restriction simplifies variance calculations, but greatly limits the class of estimators.This classical version of the Theorem gave rise to the description of OLS as the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE). However, Theorem \(4.4\) as stated above shows that OLS is the best unbiased estimator (BUE).

The derivation of the Gauss-Markov Theorem under the restriction to linear estimators is straightforward, so we now provide this demonstration. For \(\widetilde{\beta}=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y}\) we have

\[ \mathbb{E}[\widetilde{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{Y} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X} \beta, \]

the second equality because \(\mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{Y} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{X} \beta\). Then \(\widetilde{\beta}\) is unbiased for all \(\beta\) if (and only if) \(\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}=\boldsymbol{I}_{k}\). Furthermore, we saw in (4.9) that

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widetilde{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\operatorname{var}\left[\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{Y} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{A}=\boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{\sigma}^{2} \]

the last equality using the homoskedasticity assumption (4.13). To establish the Theorem we need to show that for any such matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}\),

\[ \boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{A} \geq\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \text {. } \]

Set \(\boldsymbol{C}=\boldsymbol{A}-\boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\). Note that \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C}=0\). We calculate that

\[ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{A}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{A}-\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} &=\left(\boldsymbol{C}+\boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\right)^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{C}+\boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\right)-\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\boldsymbol{C}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C}+\boldsymbol{C}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}+\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C} \\ &+\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}-\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\boldsymbol{C}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C} \geq 0 \end{aligned} \]

The final inequality states that the matrix \(\boldsymbol{C}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{C}\) is positive semi-definite which is a property of quadratic forms (see Appendix A.10). We have shown (4.14) as required.

The above derivation imposed the restriction that the estimator \(\widetilde{\beta}\) is linear in \(\boldsymbol{Y}\). The proof of Theorem \(4.4\) in the general case is considerably more advanced. Here, we provide a simplified sketch of the argument for interested readers, with a complete proof in Section 4.24. For simplicity, treat the regressors \(X\) as fixed, and suppose that \(Y\) has a density \(f(y)\) with bounded support \(\mathscr{Y}\). Without loss of generality assume that the true coefficient equals \(\beta_{0}=0\).

Since \(Y\) has bounded support \(\mathscr{Y}\) there is a set \(B \subset \mathbb{R}^{m}\) such that \(\left|y X^{\prime} \beta / \sigma^{2}\right|<1\) for all \(\beta \in B\) and \(y \in \mathscr{Y}\). For such values of \(\beta\), define the auxiliary density function

\[ f_{\beta}(y)=f(y)\left(1+y X^{\prime} \beta / \sigma^{2}\right) . \]

Under the assumptions, \(0 \leq f_{\beta}(y) \leq 2 f(y), f_{\beta}(y)\) has support \(\mathscr{Y}\), and \(\int_{\mathscr{Y}} f_{\beta}(y) d y=1\). To see the later, observe that \(\int_{\mathscr{Y}} y f(y) d y=X^{\prime} \beta_{0}=0\) under the normalization \(\beta_{0}=0\), and thus

\[ \int_{\mathscr{Y}} f_{\beta}(y) d y=\int_{\mathscr{Y}} f(y) d y+\int_{\mathscr{Y}} f(y) y d y X^{\prime} \beta / \sigma^{2}=1 \]

because \(\int_{\mathscr{Y}} f(y) d y=1\). Thus \(f_{\beta}\) is a parametric family of density functions. Evaluated at \(\beta_{0}\) we see that \(f_{0}=f\), which means that \(f_{\beta}\) is a correctly-specified parametric family with true parameter value \(\beta_{0}=0\).

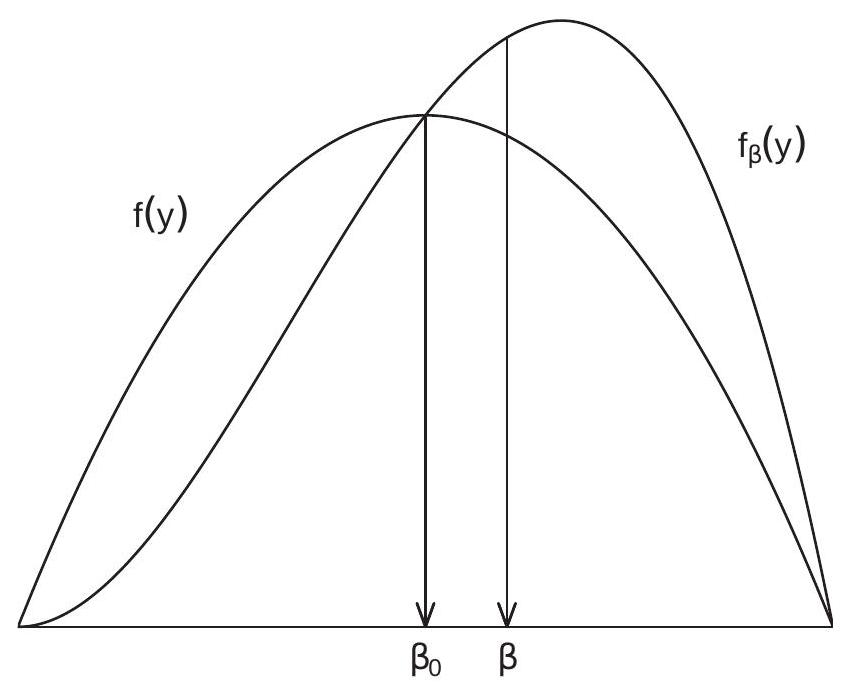

To illustrate, take the case \(X=1\). Figure 4.1 displays an example density \(f(y)=(3 / 4)\left(1-y^{2}\right)\) on \([-1,1]\) with auxiliary density \(f_{\beta}(y)=f(y)(1+y)\). We can see how the auxiliary density is a tilted version of the original density \(f(y)\).

Figure 4.1: Original and Auxiliary Density

Let \(\mathbb{E}_{\beta}\) denote expectation with respect to the auxiliary distribution. Since \(\int_{\mathscr{Y}} y f(y) d y=0\) and \(\int_{\mathscr{Y}} y^{2} f(y) d y=\) \(\sigma^{2}\), we find

\[ \mathbb{E}_{\beta}[Y]=\int_{\mathscr{Y}} y f_{\beta}(y) d y=\int_{\mathscr{Y}} y f(y) d y+\int_{\mathscr{Y}} y^{2} f(y) d y X^{\prime} \beta / \sigma^{2}=X^{\prime} \beta . \]

This shows that \(f_{\beta}\) is a regression model with regression coefficient \(\beta\).

In Figure 4.1, the means of the two densities are indicated by the arrows to the \(\mathrm{x}\)-axis. In this example we can see how the auxiliary density has a larger expected value, because the density has been tilted to the right.

The parametric family \(f_{\beta}\) over \(\beta \in B\) has the following properties: its expectation is \(X^{\prime} \beta\), its variance is finite, the true value \(\beta_{0}\) lies in the interior of \(B\), and the support of the distribution does not depend on \(\beta\).

The likelihood score of the auxiliary density function for an observation, using the fact that \(Y_{i}=e_{i}\), is

\[ S_{i}=\left.\frac{\partial}{\partial \beta}\left(\log f_{\beta}\left(Y_{i}\right)\right)\right|_{\beta=0}=\left.\frac{\partial}{\partial \beta}\left(\log f\left(e_{i}\right)+\log \left(1+e_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \beta / \sigma^{2}\right)\right)\right|_{\beta=0}=X_{i} e_{i} / \sigma^{2} . \]

Therefore the information matrix is

\[ \mathscr{I}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathbb{E}\left[S_{i} S_{i}^{\prime}\right]=\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}\left[e_{i}^{2}\right] / \sigma^{4}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right) / \sigma^{2} . \]

By assumption, \(\widetilde{\beta}\) is unbiased. The Cramér-Rao lower bound states that

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widetilde{\beta}] \geq \mathscr{I}^{-1}=\sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} . \]

This is the variance lower bound, completing the proof of Theorem 4.4.

The above argument is rather tricky. At its core is the observation that the model \(f_{\beta}\) is a submodel of the set of all linear regression models. The Cramér-Rao bound over any regular parametric submodel is a lower bound on the variance of any unbiased estimator. This means that the Cramér-Rao bound over \(f_{\beta}\) is a lower bound for unbiased estimation of the regression coefficient. The model \(f_{\beta}\) was selected judiciously so that its Cramér-Rao bound equals the variance of the least squares estimator, and this is sufficient to establish the bound.

4.9 Generalized Least Squares

Take the linear regression model in matrix format

\[ \boldsymbol{Y}=\boldsymbol{X} \beta+\boldsymbol{e} . \]

Consider a generalized situation where the observation errors are possibly correlated and/or heteroskedastic. Specifically, suppose that

\[ \begin{gathered} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=0 \\ \operatorname{var}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\Sigma \sigma^{2} \end{gathered} \]

for some \(n \times n\) matrix \(\Sigma>0\), possibly a function of \(\boldsymbol{X}\), and some scalar \(\sigma^{2}\). This includes the independent sampling framework where \(\Sigma\) is diagonal but allows for non-diagonal covariance matrices as well. As a scaled covariance matrix, \(\Sigma\) is necessarily symmetric and positive semi-definite.

Under these assumptions, by arguments similar to the previous sections we can calculate the expectation and variance of the OLS estimator:

\[ \begin{gathered} \mathbb{E}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\beta \\ \operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \Sigma \boldsymbol{X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \end{gathered} \]

(see Exercise 4.5).

Aitken (1935) established a generalization of the Gauss-Markov Theorem. The following statement is due to B. E. Hansen (2021). Theorem 4.5 Take the linear regression model (4.17)-(4.19). If \(\widetilde{\beta}\) is an unbiased estimator of \(\beta\) then

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widetilde{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] \geq \sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \Sigma^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \]

We defer the proof to Section 4.24. See also Exercise 4.6.

Theorem \(4.5\) provides a lower bound on the covariance matrix of unbiased estimators. Theorem \(4.4\) was the special case \(\Sigma=\boldsymbol{I}_{n}\).

When \(\Sigma\) is known, Aitken (1935) constructed an estimator which achieves the lower bound in Theorem 4.5. Take the linear model (4.17) and pre-multiply by \(\Sigma^{-1 / 2}\). This produces the equation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{Y}}=\widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}} \beta+\widetilde{\boldsymbol{e}}\) where \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{Y}}=\Sigma^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{Y}, \widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}}=\Sigma^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{X}\), and \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{e}}=\Sigma^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{e}\). Consider OLS estimation of \(\beta\) in this equation.

\[ \begin{aligned} \widetilde{\beta}_{\text {gls }} &=\left(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}}\right)^{-1} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{X}}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{Y}} \\ &=\left(\left(\Sigma^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{\prime}\left(\Sigma^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\right)^{-1}\left(\Sigma^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{\prime}\left(\Sigma^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{Y}\right) \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \Sigma^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \Sigma^{-1} \boldsymbol{Y} . \end{aligned} \]

This is called the Generalized Least Squares (GLS) estimator of \(\beta\).

You can calculate that

\[ \begin{gathered} \mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{\beta}_{\text {gls }} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\beta \\ \operatorname{var}\left[\widetilde{\beta}_{\text {gls }} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \Sigma^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} . \end{gathered} \]

This shows that the GLS estimator is unbiased and has a covariance matrix which equals the lower bound from Theorem 4.5. This shows that the lower bound is sharp. GLS is thus efficient in the class of unbiased estimators.

In the linear regression model with independent observations and known conditional variances, so that \(\Sigma=\boldsymbol{D}=\operatorname{diag}\left(\sigma_{1}^{2}, \ldots, \sigma_{n}^{2}\right)\), the GLS estimator takes the form

\[ \begin{aligned} \widetilde{\beta}_{\mathrm{gls}} &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D}^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D}^{-1} \boldsymbol{Y} \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sigma_{i}^{-2} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sigma_{i}^{-2} X_{i} Y_{i}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

The assumption \(\Sigma>0\) in this case reduces to \(\sigma_{i}^{2}>0\) for \(i=1, \ldots n\).

In most settings the matrix \(\Sigma\) is unknown so the GLS estimator is not feasible. However, the form of the GLS estimator motivates feasible versions, effectively by replacing \(\Sigma\) with a suitable estimator.

4.10 Residuals

What are some properties of the residuals \(\widehat{e}_{i}=Y_{i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}\) and prediction errors \(\widetilde{e}_{i}=Y_{i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}\) in the context of the linear regression model?

Recall from (3.24) that we can write the residuals in vector notation as \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{e}}=\boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{e}\) where \(\boldsymbol{M}=\boldsymbol{I}_{n}-\) \(\boldsymbol{X}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\prime}\) is the orthogonal projection matrix. Using the properties of conditional expectation

\[ \mathbb{E}[\widehat{\boldsymbol{e}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{M e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{M} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=0 \]

and

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widehat{\boldsymbol{e}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\operatorname{var}[\boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{M} \operatorname{var}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] \boldsymbol{M}=\boldsymbol{M D} \boldsymbol{M} \]

where \(\boldsymbol{D}\) is defined in (4.8).

We can simplify this expression under the assumption of conditional homoskedasticity

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X\right]=\sigma^{2} . \]

In this case (4.25) simplifies to

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widehat{\boldsymbol{e}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{M} \sigma^{2} . \]

In particular, for a single observation \(i\) we can find the variance of \(\widehat{e}_{i}\) by taking the \(i^{t h}\) diagonal element of (4.26). Since the \(i^{t h}\) diagonal element of \(M\) is \(1-h_{i i}\) as defined in (3.40) we obtain

\[ \operatorname{var}\left[\widehat{e}_{i} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{e}_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\left(1-h_{i i}\right) \sigma^{2} . \]

As this variance is a function of \(h_{i i}\) and hence \(X_{i}\) the residuals \(\widehat{e}_{i}\) are heteroskedastic even if the errors \(e_{i}\) are homoskedastic. Notice as well that (4.27) implies \(\widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\) is a biased estimator of \(\sigma^{2}\).

Similarly, recall from (3.45) that the prediction errors \(\widetilde{e}_{i}=\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1} \widehat{e}_{i}\) can be written in vector notation as \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{e}}=\boldsymbol{M}^{*} \widehat{\boldsymbol{e}}\) where \(\boldsymbol{M}^{*}\) is a diagonal matrix with \(i^{t h}\) diagonal element \(\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1}\). Thus \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{e}}=\boldsymbol{M}^{*} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{e}\). We can calculate that

\[ \mathbb{E}[\tilde{\boldsymbol{e}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{M}^{*} \boldsymbol{M} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=0 \]

and

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widetilde{\boldsymbol{e}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{M}^{*} \boldsymbol{M} \operatorname{var}[\boldsymbol{e} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{M}^{*}=\boldsymbol{M}^{*} \boldsymbol{M D} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{M}^{*} \]

which simplifies under homoskedasticity to

\[ \operatorname{var}[\widetilde{\boldsymbol{e}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{M}^{*} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{M}^{*} \sigma^{2}=\boldsymbol{M}^{*} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{M}^{*} \sigma^{2} . \]

The variance of the \(i^{t h}\) prediction error is then

\[ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{var}\left[\widetilde{e}_{i} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] &=\mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{e}_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \\ &=\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1}\left(1-h_{i i}\right)\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2} \\ &=\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2} . \end{aligned} \]

A residual with constant conditional variance can be obtained by rescaling. The standardized residuals are

\[ \bar{e}_{i}=\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1 / 2} \widehat{e}_{i}, \]

and in vector notation

\[ \overline{\boldsymbol{e}}=\left(\bar{e}_{1}, \ldots, \bar{e}_{n}\right)^{\prime}=\boldsymbol{M}^{* 1 / 2} \boldsymbol{M e} . \]

From the above calculations, under homoskedasticity,

\[ \operatorname{var}[\overline{\boldsymbol{e}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]=\boldsymbol{M}^{* 1 / 2} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{M}^{* 1 / 2} \sigma^{2} \]

and

\[ \operatorname{var}\left[\bar{e}_{i} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[\bar{e}_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\sigma^{2} \]

and thus these standardized residuals have the same bias and variance as the original errors when the latter are homoskedastic.

4.11 Estimation of Error Variance

The error variance \(\sigma^{2}=\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2}\right]\) can be a parameter of interest even in a heteroskedastic regression or a projection model. \(\sigma^{2}\) measures the variation in the “unexplained” part of the regression. Its method of moments estimator (MME) is the sample average of the squared residuals:

\[ \widehat{\sigma}^{2}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2} . \]

In the linear regression model we can calculate the expectation of \(\widehat{\sigma}^{2}\). From (3.28) and the properties of the trace operator observe that

\[ \widehat{\sigma}^{2}=\frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{e}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{e}=\frac{1}{n} \operatorname{tr}\left(\boldsymbol{e}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{M} \boldsymbol{e}\right)=\frac{1}{n} \operatorname{tr}\left(\boldsymbol{M e}^{\prime}\right) . \]

Then

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\sigma}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] &=\frac{1}{n} \operatorname{tr}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{M e e}^{\prime} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]\right) \\ &=\frac{1}{n} \operatorname{tr}\left(\boldsymbol{M}\left[\boldsymbol{e} \boldsymbol{e}^{\prime} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]\right) \\ &=\frac{1}{n} \operatorname{tr}(\boldsymbol{M D}) \\ &=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-h_{i i}\right) \sigma_{i}^{2} \end{aligned} \]

The final equality holds because the trace is the sum of the diagonal elements of \(\boldsymbol{M D}\), and because \(\boldsymbol{D}\) is diagonal the diagonal elements of \(M D\) are the product of the diagonal elements of \(M\) and \(\boldsymbol{D}\) which are \(1-h_{i i}\) and \(\sigma_{i}^{2}\), respectively.

Adding the assumption of conditional homoskedasticity \(\mathbb{E}\left[e^{2} \mid X\right]=\sigma^{2}\) so that \(\boldsymbol{D}=\boldsymbol{I}_{n} \sigma^{2}\), then (4.30) simplifies to

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\sigma}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\frac{1}{n} \operatorname{tr}\left(\boldsymbol{M} \sigma^{2}\right)=\sigma^{2}\left(\frac{n-k}{n}\right) \]

the final equality by (3.22). This calculation shows that \(\widehat{\sigma}^{2}\) is biased towards zero. The order of the bias depends on \(k / n\), the ratio of the number of estimated coefficients to the sample size.

Another way to see this is to use (4.27). Note that

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\sigma}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{e}_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-h_{i i}\right) \sigma^{2}=\left(\frac{n-k}{n}\right) \sigma^{2} \]

the last equality using Theorem 3.6.

Since the bias takes a scale form a classic method to obtain an unbiased estimator is by rescaling. Define

\[ s^{2}=\frac{1}{n-k} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2} . \]

By the above calculation \(\mathbb{E}\left[s^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\sigma^{2}\) and \(\mathbb{E}\left[s^{2}\right]=\sigma^{2}\). Hence the estimator \(s^{2}\) is unbiased for \(\sigma^{2}\). Consequently, \(s^{2}\) is known as the bias-corrected estimator for \(\sigma^{2}\) and in empirical practice \(s^{2}\) is the most widely used estimator for \(\sigma^{2}\). Interestingly, this is not the only method to construct an unbiased estimator for \(\sigma^{2}\). An estimator constructed with the standardized residuals \(\bar{e}_{i}\) from (4.28) is

\[ \bar{\sigma}^{2}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \bar{e}_{i}^{2}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2} . \]

You can show (see Exercise 4.9) that

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\bar{\sigma}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\sigma^{2} \]

and thus \(\bar{\sigma}^{2}\) is unbiased for \(\sigma^{2}\) (in the homoskedastic linear regression model).

When \(k / n\) is small the estimators \(\widehat{\sigma}^{2}, s^{2}\) and \(\bar{\sigma}^{2}\) are likely to be similar to one another. However, if \(k / n\) is large then \(s^{2}\) and \(\bar{\sigma}^{2}\) are generally preferred to \(\widehat{\sigma}^{2}\). Consequently it is best to use one of the biascorrected variance estimators in applications.

4.12 Mean-Square Forecast Error

One use of an estimated regression is to predict out-of-sample. Consider an out-of-sample realization \(\left(Y_{n+1}, X_{n+1}\right)\) where \(X_{n+1}\) is observed but not \(Y_{n+1}\). Given the coefficient estimator \(\widehat{\beta}\) the standard point estimator of \(\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{n+1} \mid X_{n+1}\right]=X_{n+1}^{\prime} \beta\) is \(\widetilde{Y}_{n+1}=X_{n+1}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}\). The forecast error is the difference between the actual value \(Y_{n+1}\) and the point forecast \(\widetilde{Y}_{n+1}\). This is the forecast error \(\widetilde{e}_{n+1}=Y_{n+1}-\widetilde{Y}_{n+1}\). The meansquared forecast error (MSFE) is its expected squared value \(\operatorname{MSFE}_{n}=\mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{e}_{n+1}^{2}\right]\). In the linear regression model \(\widetilde{e}_{n+1}=e_{n+1}-X_{n+1}^{\prime}(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)\) so

\[ \operatorname{MSFE}_{n}=\mathbb{E}\left[e_{n+1}^{2}\right]-2 \mathbb{E}\left[e_{n+1} X_{n+1}^{\prime}(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)\right]+\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1}^{\prime}(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)^{\prime} X_{n+1}\right] . \]

The first term in (4.33) is \(\sigma^{2}\). The second term in (4.33) is zero because \(e_{n+1} X_{n+1}^{\prime}\) is independent of \(\widehat{\beta}-\beta\) and both are mean zero. Using the properties of the trace operator the third term in (4.33) is

\[ \begin{aligned} &\operatorname{tr}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1} X_{n+1}^{\prime}\right] \mathbb{E}\left[(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)^{\prime}\right]\right) \\ &=\operatorname{tr}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1} X_{n+1}^{\prime}\right] \mathbb{E}\left[\mathbb{E}\left[(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)^{\prime} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]\right]\right) \\ &=\operatorname{tr}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1} X_{n+1}^{\prime}\right] \mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\right]\right) \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[\operatorname{tr}\left(\left(X_{n+1} X_{n+1}^{\prime}\right) \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\right)\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} X_{n+1}\right] \end{aligned} \]

where we use the fact that \(X_{n+1}\) is independent of \(\widehat{\beta}\), the definition \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\mathbb{E}\left[(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)(\widehat{\beta}-\beta)^{\prime} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]\), and the fact that \(X_{n+1}\) is independent of \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\). Thus

\[ \operatorname{MSFE}_{n}=\sigma^{2}+\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} X_{n+1}\right] . \]

Under conditional homoskedasticity this simplifies to

\[ \operatorname{MSFE}_{n}=\sigma^{2}\left(1+\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1}^{\prime}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} X_{n+1}\right]\right) . \]

A simple estimator for the MSFE is obtained by averaging the squared prediction errors (3.46)

\[ \widetilde{\sigma}^{2}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \widetilde{e}_{i}^{2} \]

where \(\widetilde{e}_{i}=Y_{i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}=\widehat{e}_{i}\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1}\). Indeed, we can calculate that

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\right] &=\mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{e}_{i}^{2}\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(e_{i}-X_{i}^{\prime}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right)\right)^{2}\right] \\ &=\sigma^{2}+\mathbb{E}\left[X_{i}^{\prime}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right)\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right)^{\prime} X_{i}\right] . \end{aligned} \]

By a similar calculation as in (4.34) we find

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\right]=\sigma^{2}+\mathbb{E}\left[X_{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}} X_{i}\right]=\operatorname{MSFE}_{n-1} . \]

This is the MSFE based on a sample of size \(n-1\) rather than size \(n\). The difference arises because the in-sample prediction errors \(\widetilde{e}_{i}\) for \(i \leq n\) are calculated using an effective sample size of \(n-1\), while the out-of sample prediction error \(\widetilde{e}_{n+1}\) is calculated from a sample with the full \(n\) observations. Unless \(n\) is very small we should expect \(\operatorname{MSFE}_{n-1}\) (the MSFE based on \(n-1\) observations) to be close to \(\mathrm{MSFE}_{n}\) (the MSFE based on \(n\) observations). Thus \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\) is a reasonable estimator for MSFE \(n\).

Theorem 4.6 MSFE In the linear regression model (Assumption 4.2) and i.i.d. sampling (Assumption 4.1)

\[ \operatorname{MSFE}_{n}=\mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{e}_{n+1}^{2}\right]=\sigma^{2}+\mathbb{E}\left[X_{n+1}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} X_{n+1}\right] \]

where \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\operatorname{var}[\widehat{\beta} \mid \boldsymbol{X}]\). Furthermore, \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\) defined in (3.46) is an unbiased estimator of \(\operatorname{MSFE}_{n-1}\), because \(\mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\right]=\operatorname{MSFE}_{n-1}\).

4.13 Covariance Matrix Estimation Under Homoskedasticity

For inference we need an estimator of the covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\) of the least squares estimator. In this section we consider the homoskedastic regression model (Assumption 4.3).

Under homoskedasticity the covariance matrix takes the simple form

\[ \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2} \]

which is known up to the scale \(\sigma^{2}\). In Section \(4.11\) we discussed three estimators of \(\sigma^{2}\). The most commonly used choice is \(s^{2}\) leading to the classic covariance matrix estimator

\[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} s^{2} . \]

Since \(s^{2}\) is conditionally unbiased for \(\sigma^{2}\) it is simple to calculate that \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}\) is conditionally unbiased for \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\) under the assumption of homoskedasticity:

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[s^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2}=\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} . \]

This was the dominant covariance matrix estimator in applied econometrics for many years and is still the default method in most regression packages. For example, Stata uses the covariance matrix estimator (4.35) by default in linear regression unless an alternative is specified. If the estimator (4.35) is used but the regression error is heteroskedastic it is possible for \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}\) to be quite biased for the correct covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\). For example, suppose \(k=1\) and \(\sigma_{i}^{2}=X_{i}^{2}\) with \(\mathbb{E}[X]=0\). The ratio of the true variance of the least squares estimator to the expectation of the variance estimator is

\[ \frac{\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}}{\mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i}^{4}}{\sigma^{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i}^{2}} \simeq \frac{\mathbb{E}\left[X^{4}\right]}{\left(\mathbb{E}\left[X^{2}\right]\right)^{2}} \stackrel{\text { def }}{=} \kappa \]

(Notice that we use the fact that \(\sigma_{i}^{2}=X_{i}^{2}\) implies \(\sigma^{2}=\mathbb{E}\left[\sigma_{i}^{2}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[X^{2}\right]\).) The constant \(\kappa\) is the standardized fourth moment (or kurtosis) of the regressor \(X\) and can be any number greater than one. For example, if \(X \sim \mathrm{N}\left(0, \sigma^{2}\right)\) then \(\kappa=3\), so the true variance \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\) is three times larger than the expected homoskedastic estimator \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}\). But \(\kappa\) can be much larger. Take, for example, the variable wage in the CPS data set. It satisfies \(\kappa=30\) so that if the conditional variance equals \(\sigma_{i}^{2}=X_{i}^{2}\) then the true variance \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\) is 30 times larger than the expected homoskedastic estimator \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}\). While this is an extreme case the point is that the classic covariance matrix estimator (4.35) may be quite biased when the homoskedasticity assumption fails.

4.14 Covariance Matrix Estimation Under Heteroskedasticity

In the previous section we showed that that the classic covariance matrix estimator can be highly biased if homoskedasticity fails. In this section we show how to construct covariance matrix estimators which do not require homoskedasticity.

Recall that the general form for the covariance matrix is

\[ \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} . \]

with \(\boldsymbol{D}\) defined in (4.8). This depends on the unknown matrix \(\boldsymbol{D}\) which we can write as

\[ \boldsymbol{D}=\operatorname{diag}\left(\sigma_{1}^{2}, \ldots, \sigma_{n}^{2}\right)=\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{e} \boldsymbol{e}^{\prime} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\mathbb{E}[\widetilde{\boldsymbol{D}} \mid \boldsymbol{X}] \]

where \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{D}}=\operatorname{diag}\left(e_{1}^{2}, \ldots, e_{n}^{2}\right)\). Thus \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{D}}\) is a conditionally unbiased estimator for \(\boldsymbol{D}\). If the squared errors \(e_{i}^{2}\) were observable, we could construct an unbiased estimator for \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\) as

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\text {ideal }} &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \widetilde{\boldsymbol{D}} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} e_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \end{aligned} \]

Indeed,

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\text {ideal }} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}\left[e_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \sigma_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{X}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}=\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} \end{aligned} \]

verifying that \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\text {ideal }}\) is unbiased for \(\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}\). Since the errors \(e_{i}^{2}\) are unobserved \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\text {ideal }}\) is not a feasible estimator. However, we can replace \(e_{i}^{2}\) with the squared residuals \(\widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\). Making this substitution we obtain the estimator

\[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 0}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} . \]

The label “HC” refers to “heteroskedasticity-consistent”. The label “HC0” refers to this being the baseline heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator.

We know, however, that \(\widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\) is biased towards zero (recall equation (4.27)). To estimate the variance \(\sigma^{2}\) the unbiased estimator \(s^{2}\) scales the moment estimator \(\widehat{\sigma}^{2}\) by \(n /(n-k)\). Making the same adjustment we obtain the estimator

\[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC1}}=\left(\frac{n}{n-k}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} . \]

While the scaling by \(n /(n-k)\) is \(a d h o c, \mathrm{HCl}\) is often recommended over the unscaled HC0 estimator.

Alternatively, we could use the standardized residuals \(\bar{e}_{i}\) or the prediction errors \(\widetilde{e}_{i}\), yielding the “HC2” and “HC3” estimators

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 2} &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \bar{e}_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \end{aligned} \]

and

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 3} &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \tilde{e}_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-2} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} . \end{aligned} \]

The four estimators \(\mathrm{HC}\), \(\mathrm{HC1}\), HC2, and HC3 are collectively called robust, heteroskedasticityconsistent, or heteroskedasticity-robust covariance matrix estimators. The HC0 estimator was first developed by Eicker (1963) and introduced to econometrics by White (1980) and is sometimes called the Eicker-White or White covariance matrix estimator. The degree-of-freedom adjustment in \(\mathrm{HCl}\) was recommended by Hinkley (1977) and is the default robust covariance matrix estimator implemented in Stata. It is implement by the “, \(r\)” option. In current applied econometric practice this is the most popular covariance matrix estimator. The HC2 estimator was introduced by Horn, Horn and Duncan (1975) and is implemented using the vce (hc2) option in Stata. The HC3 estimator was derived by MacKinnon and White (1985) from the jackknife principle (see Section 10.3), and by Andrews (1991a) based on the principle of leave-one-out cross-validation, and is implemented using the vce(hc3) option in Stata.

Since \(\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-2}>\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1}>1\) it is straightforward to show that

\[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 0}<\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 2}<\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 3} . \]

(See Exercise 4.10.) The inequality \(\boldsymbol{A}<\boldsymbol{B}\) when applied to matrices means that the matrix \(\boldsymbol{B}-\boldsymbol{A}\) is positive definite. In general, the bias of the covariance matrix estimators is complicated but simplify under the assumption of homoskedasticity (4.3). For example, using (4.27),

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 0} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{e}_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime}\left(1-h_{i i}\right) \sigma^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2}-\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} h_{i i}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2} \\ &<\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2}=\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} \end{aligned} \]

This calculation shows that \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 0}\) is biased towards zero.

By a similar calculation (again under homoskedasticity) we can calculate that the HC2 estimator is unbiased

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \sigma^{2} . \]

(See Exercise 4.11.)

It might seem rather odd to compare the bias of heteroskedasticity-robust estimators under the assumption of homoskedasticity but it does give us a baseline for comparison.

Another interesting calculation shows that in general (that is, without assuming homoskedasticity) the HC3 estimator is biased away from zero. Indeed, using the definition of the prediction errors (3.44)

\[ \widetilde{e}_{i}=Y_{i}-X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}=e_{i}-X_{i}^{\prime}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right) \]

so

\[ \widetilde{e}_{i}^{2}=e_{i}^{2}-2 X_{i}^{\prime}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right) e_{i}+\left(X_{i}^{\prime}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right)\right)^{2} . \]

Note that \(e_{i}\) and \(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}\) are functions of non-overlapping observations and are thus independent. Hence \(\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right) e_{i} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]=0\) and

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\widetilde{e}_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] &=\mathbb{E}\left[e_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]-2 X_{i}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right) e_{i} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]+\mathbb{E}\left[\left(X_{i}^{\prime}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right)\right)^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \\ &=\sigma_{i}^{2}+\mathbb{E}\left[\left(X_{i}^{\prime}\left(\widehat{\beta}_{(-i)}-\beta\right)\right)^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] \\ & \geq \sigma_{i}^{2} . \end{aligned} \]

It follows that

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 3} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right] &=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \mathbb{E}\left[\tilde{e}_{i}^{2} \mid \boldsymbol{X}\right]\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1} \\ & \geq\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \sigma_{i}^{2}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}=\boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}} \end{aligned} \]

This means that the HC3 estimator is conservative in the sense that it is weakly larger (in expectation) than the correct variance for any realization of \(\boldsymbol{X}\).

We have introduced five covariance matrix estimators, including the homoskedastic estimator \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}\) and the four HC estimators. Which should you use? The classic estimator \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}\) is typically a poor choice as it is only valid under the unlikely homoskedasticity restriction. For this reason it is not typically used in contemporary econometric research. Unfortunately, standard regression packages set their default choice as \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}\) so users must intentionally select a robust covariance matrix estimator.

Of the four robust estimators \(\mathrm{HCl}\) is the most commonly used as it is the default robust covariance matrix option in Stata. However, HC2 and HC3 are preferred. HC2 is unbiased (under homoskedasticity) and HC3 is conservative for any \(\boldsymbol{X}\). In most applications \(\mathrm{HC} 1, \mathrm{HC} 2\), and \(\mathrm{HC} 3\) will be similar so this choice will not matter. The context where the estimators can differ substantially is when the sample has a large leverage value \(h_{i i}\) for at least one observation. You can see this by comparing the formulas (4.37), (4.38), and (4.39) and noting that the only difference is the scaling by the leverage values \(h_{i i}\). If there is an observation with \(h_{i i}\) close to one, then \(\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1}\) and \(\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-2}\) will be large, giving this observation much greater weight in the covariance matrix formula.

4.15 Standard Errors

A variance estimator such as \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}\) is an estimator of the variance of the distribution of \(\widehat{\beta}\). A more easily interpretable measure of spread is its square root - the standard deviation. This is so important when discussing the distribution of parameter estimators we have a special name for estimates of their standard deviation.

Definition \(4.2\) A standard error \(s(\widehat{\beta})\) for a real-valued estimator \(\widehat{\beta}\) is an estimator of the standard deviation of the distribution of \(\widehat{\beta}\).

When \(\beta\) is a vector with estimator \(\widehat{\beta}\) and covariance matrix estimator \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}\), standard errors for individual elements are the square roots of the diagonal elements of \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}\). That is,

\[ s\left(\widehat{\beta}_{j}\right)=\sqrt{\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}_{j}}}=\sqrt{\left[\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}\right]_{j j}} \]

When the classical covariance matrix estimator (4.35) is used the standard error takes the simple form

\[ s\left(\widehat{\beta}_{j}\right)=s \sqrt{\left[\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}\right]_{j j}} . \]

As we discussed in the previous section there are multiple possible covariance matrix estimators so standard errors are not unique. It is therefore important to understand what formula and method is used by an author when studying their work. It is also important to understand that a particular standard error may be relevant under one set of model assumptions but not under another set of assumptions.

To illustrate, we return to the log wage regression (3.12) of Section 3.7. We calculate that \(s^{2}=0.160\). Therefore the homoskedastic covariance matrix estimate is

\[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{0}=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 5010 & 314 \\ 314 & 20 \end{array}\right)^{-1} 0.160=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0.002 & -0.031 \\ -0.031 & 0.499 \end{array}\right) \]

We also calculate that

\[ \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(1-h_{i i}\right)^{-1} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 763.26 & 48.513 \\ 48.513 & 3.1078 \end{array}\right) . \]

Therefore the HC2 covariance matrix estimate is

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC} 2} &=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 5010 & 314 \\ 314 & 20 \end{array}\right)^{-1}\left(\begin{array}{cc} 763.26 & 48.513 \\ 48.513 & 3.1078 \end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{cc} 5010 & 314 \\ 314 & 20 \end{array}\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0.001 & -0.015 \\ -0.015 & 0.243 \end{array}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

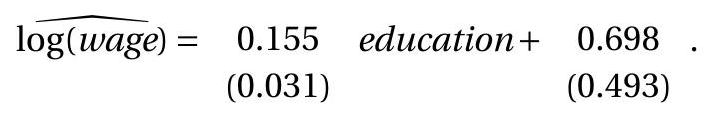

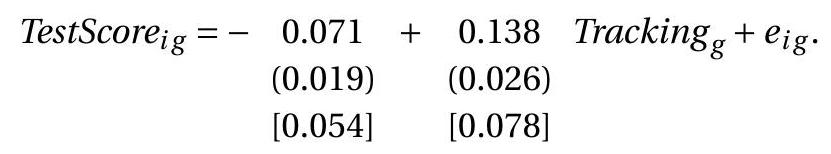

The standard errors are the square roots of the diagonal elements of these matrices. A conventional format to write the estimated equation with standard errors is

Alternatively, standard errors could be calculated using the other formulae. We report the different standard errors in the following table.

Table 4.1: Standard Errors

| Education | Intercept | |

|---|---|---|

| Homoskedastic (4.35) | \(0.045\) | \(0.707\) |

| HC0 (4.36) | \(0.029\) | \(0.461\) |

| HC1 \((4.37)\) | \(0.030\) | \(0.486\) |

| HC2 \((4.38)\) | \(0.031\) | \(0.493\) |

| HC3 \((4.39)\) | \(0.033\) | \(0.527\) |

The homoskedastic standard errors are noticeably different (larger in this case) than the others. The robust standard errors are reasonably close to one another though the HC3 standard errors are larger than the others.

4.16 Estimation with Sparse Dummy Variables

The heteroskedasticity-robust covariance matrix estimators can be quite imprecise in some contexts. One is in the presence of sparse dummy variables - when a dummy variable only takes the value 1 or 0 for very few observations. In these contexts one component of the covariance matrix is estimated on just those few observations and will be imprecise. This is effectively hidden from the user. To see the problem, let \(D\) be a dummy variable (takes on the values 1 and 0 ) and consider the dummy variable regression

\[ Y=\beta_{1} D+\beta_{2}+e . \]

The number of observations for which \(D_{i}=1\) is \(n_{1}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} D_{i}\). The number of observations for which \(D_{i}=0\) is \(n_{2}=n-n_{1}\). We say the design is sparse if \(n_{1}\) or \(n_{2}\) is small.

To simplify our analysis, we take the extreme case \(n_{1}=1\). The ideas extend to the case of \(n_{1}>1\) but small, though with less dramatic effects.

In the regression model (4.45) we can calculate that the true covariance matrix of the least squares estimator for the coefficients under the simplifying assumption of conditional homoskedasticity is

\[ \boldsymbol{V}_{\widehat{\beta}}=\sigma^{2}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{X}\right)^{-1}=\sigma^{2}\left(\begin{array}{ll} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & n \end{array}\right)^{-1}=\frac{\sigma^{2}}{n-1}\left(\begin{array}{cc} n & -1 \\ -1 & 1 \end{array}\right) \]

In particular, the variance of the estimator for the coefficient on the dummy variable is

\[ V_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}=\sigma^{2} \frac{n}{n-1} . \]

Essentially, the coefficient \(\beta_{1}\) is estimated from a single observation so its variance is roughly unaffected by sample size. An important message is that certain coefficient estimators in the presence of sparse dummy variables will be imprecise, regardless of the sample size. A large sample alone is not sufficient to ensure precise estimation.

Now let’s examine the standard HC1 covariance matrix estimator (4.37). The regression has perfect fit for the observation for which \(D_{i}=1\) so the corresponding residual is \(\widehat{e}_{i}=0\). It follows that \(D_{i} \widehat{e}_{i}=0\) for all \(i\) (either \(D_{i}=0\) or \(\widehat{e}_{i}=0\) ). Hence

\[ \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_{i} X_{i}^{\prime} \hat{e}_{i}^{2}=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2} \end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & (n-2) s^{2} \end{array}\right) \]

where \(s^{2}=(n-2)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}\) is the bias-corrected estimator of \(\sigma^{2}\). Together we find that

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC1}} &=\left(\frac{n}{n-2}\right) \frac{1}{(n-1)^{2}}\left(\begin{array}{cc} n & -1 \\ -1 & 1 \end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & (n-2) s^{2} \end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{cc} n & -1 \\ -1 & 1 \end{array}\right) \\ &=s^{2} \frac{n}{(n-1)^{2}}\left(\begin{array}{cc} 1 & -1 \\ -1 & 1 \end{array}\right) . \end{aligned} \]

In particular, the estimator for \(V_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}\) is

\[ \widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC} 1}=s^{2} \frac{n}{(n-1)^{2}} \]

It has expectation

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC1}}\right]=\sigma^{2} \frac{n}{(n-1)^{2}}=\frac{V_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}}{n-1}<<V_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}} . \]

The variance estimator \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HCl}}\) is extremely biased for \(V_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}\). It is too small by a multiple of \(n\) ! The reported variance - and standard error - is misleadingly small. The variance estimate erroneously mis-states the precision of \(\widehat{\beta}_{1}\).

The fact that \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HCl}}\) is biased is unlikely to be noticed by an applied researcher. Nothing in the reported output will alert a researcher to the problem. Another way to see the issue is to consider the estimator \(\widehat{\theta}=\widehat{\beta}_{1}+\widehat{\beta}_{2}\) for the sum of the coefficients \(\theta=\beta_{1}+\beta_{2}\). This estimator has true variance \(\sigma^{2}\). The variance estimator, however is \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\theta}}^{\mathrm{HC1}}=0\) ! (It equals the sum of the four elements in \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\widehat{\beta}}^{\mathrm{HC1}}\) ). Clearly, the estimator ” 0 ” is biased for the true value \(\sigma^{2}\).

Another insight is to examine the leverage values. The (single) observation with \(D_{i}=1\) has

\[ h_{i i}=\frac{1}{n-1}\left(\begin{array}{ll} 1 & 1 \end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{cc} n & -1 \\ -1 & 1 \end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l} 1 \\ 1 \end{array}\right)=1 . \]

This is an extreme leverage value.

A possible solution is to replace the biased covariance matrix estimator \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC1}}\) with the unbiased estimator \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC} 2}\) (unbiased under homoskedasticity) or the conservative estimator \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC}} .\) Neither approach can be done in the extreme sparse case \(n_{1}=1\) (for \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC} 2}\) and \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC}}\) cannot be calculated if \(h_{i i}=1\) for any observation) but applies otherwise. When \(h_{i i}=1\) for an observation then \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC} 2}\) and \(\widehat{V}_{\widehat{\beta}_{1}}^{\mathrm{HC} 3}\) cannot be calculated. In this case unbiased covariance matrix estimation appears to be impossible.

It is unclear if there is a best practice to avoid this situation. Once possibility is to calculate the maximum leverage value. If it is very large calculate the standard errors using several methods to see if variation occurs.

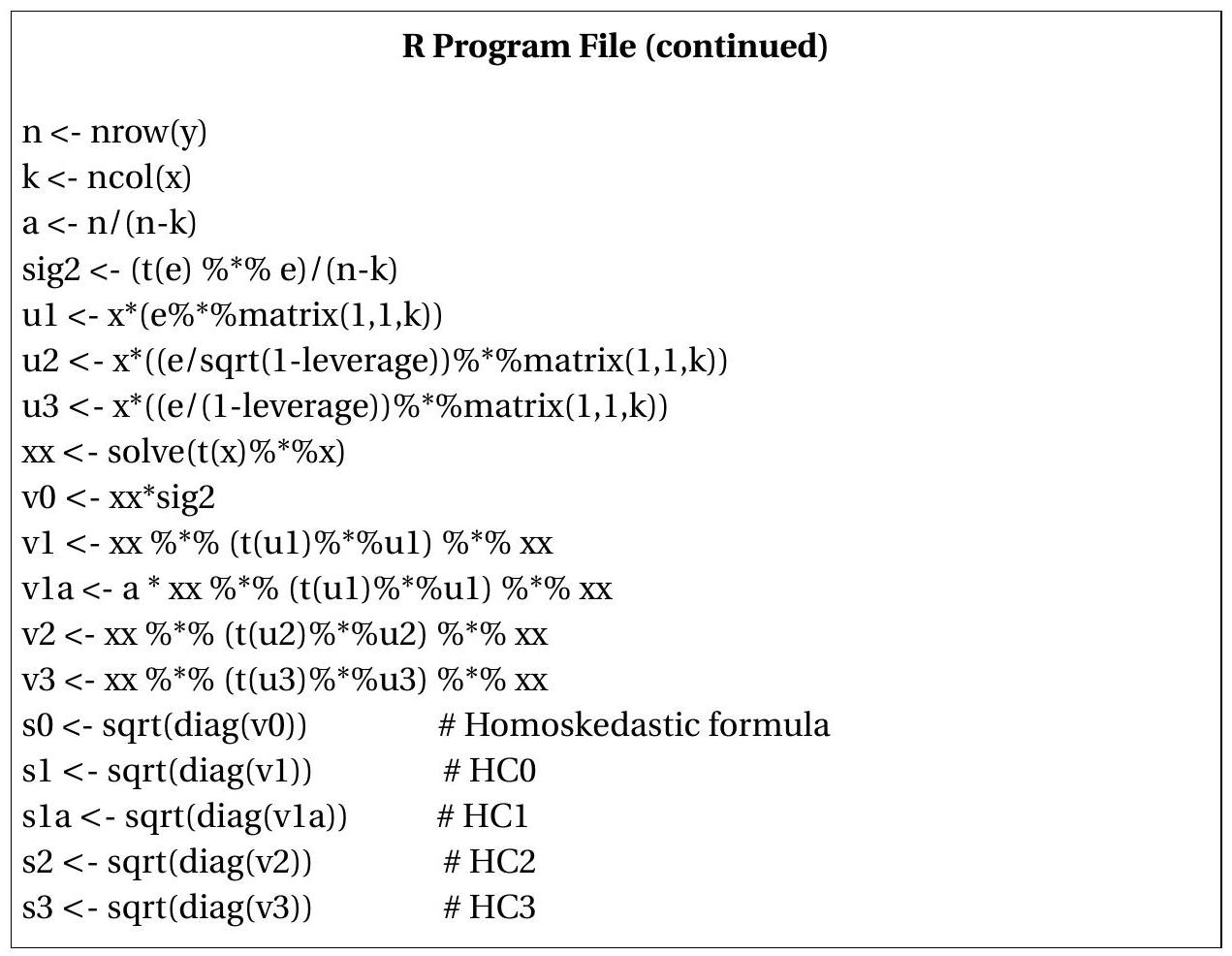

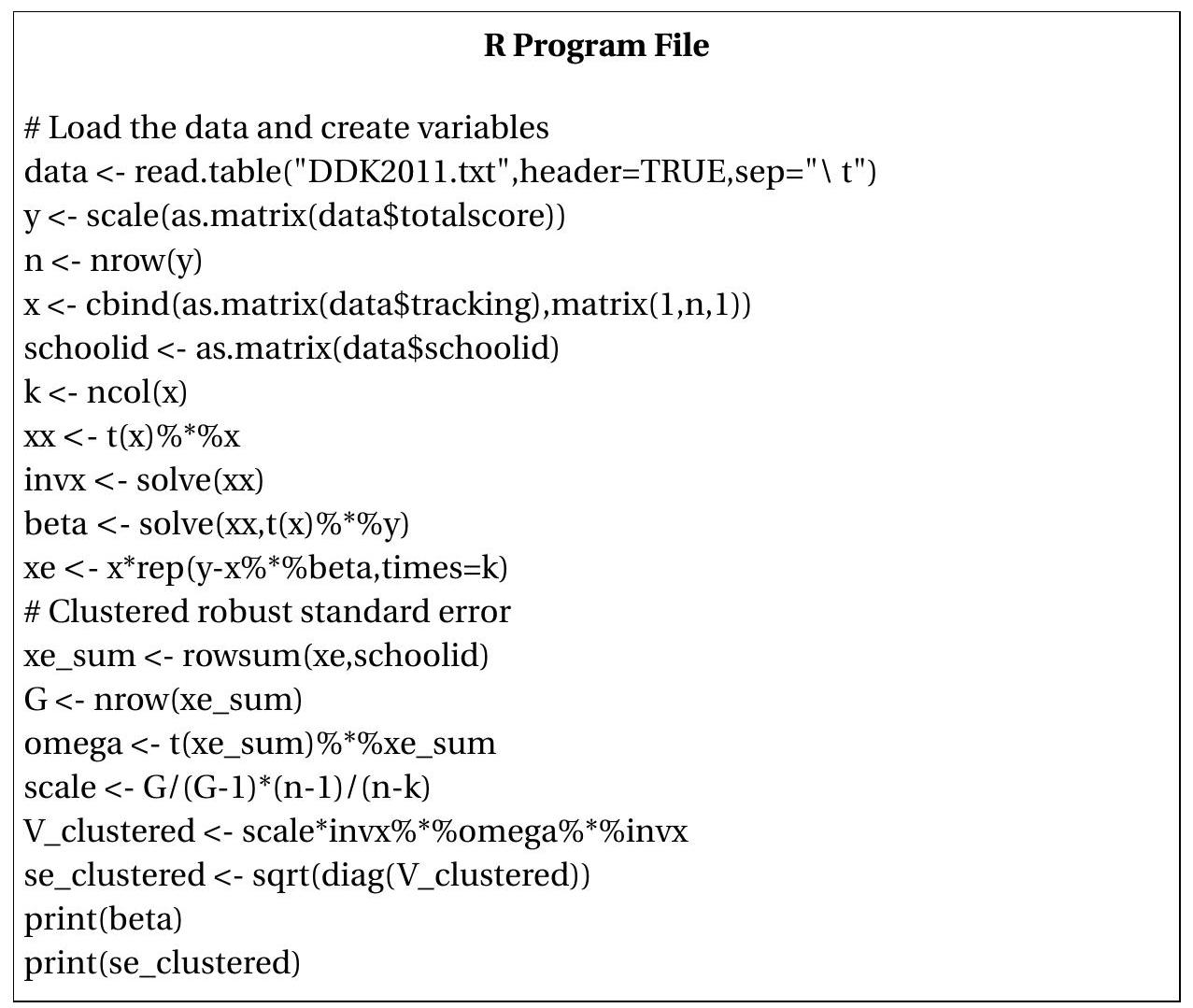

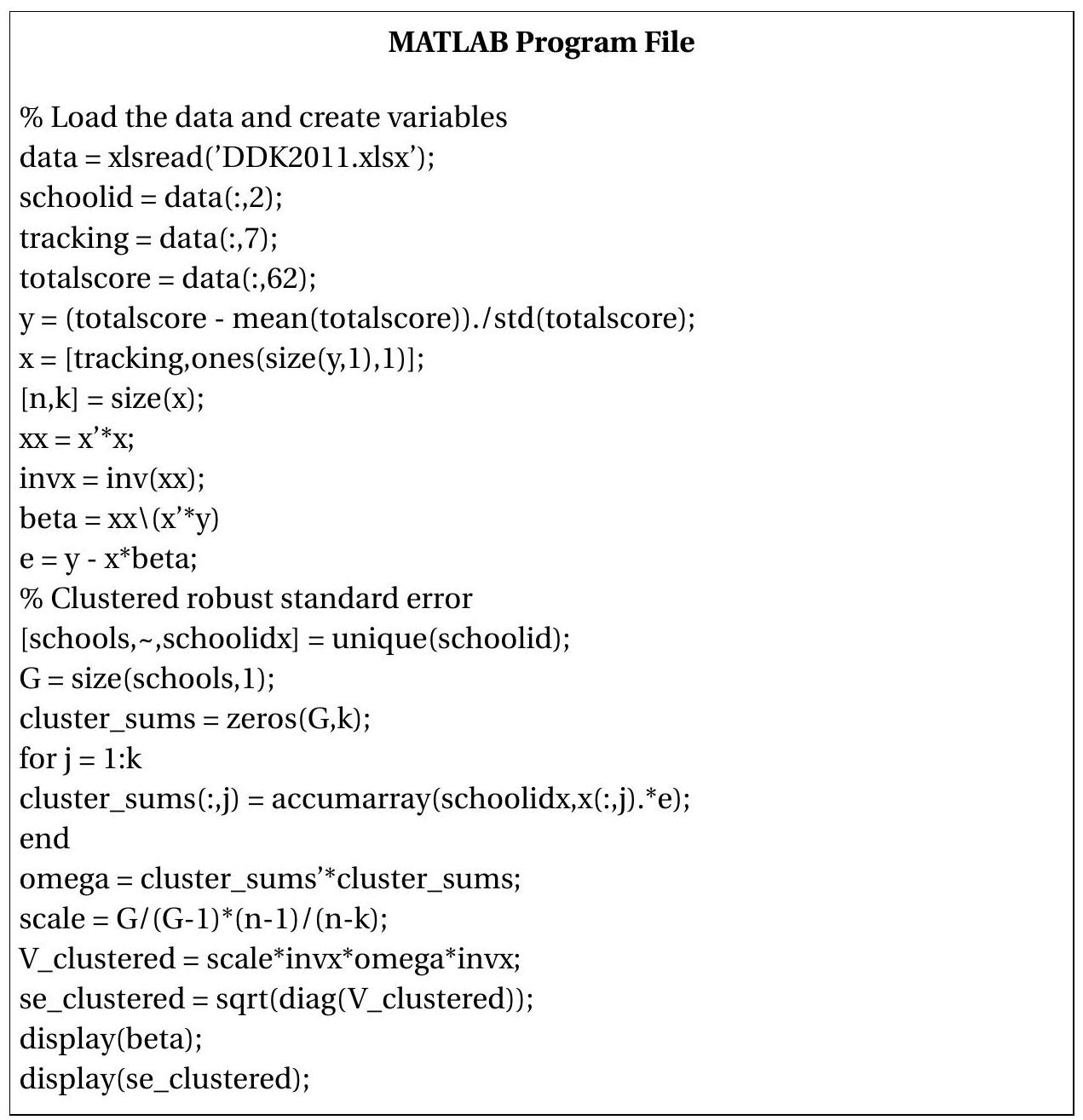

4.17 Computation

We illustrate methods to compute standard errors for equation (3.13) extending the code of Section \(3.25 .\)

Stata do File (continued)

- Homoskedastic formula (4.35):

reg wage education experience exp2 if \((\mathrm{mnwf}==1)\)

- \(\quad\) HC1 formula (4.37):

reg wage education experience exp2 if \((\operatorname{mnwf}==1), \mathrm{r}\)

- \(\mathrm{HC} 2\) formula (4.38):

reg wage education experience \(\exp 2\) if \((\mathrm{mnwf}==1)\), vce \((\mathrm{hc} 2)\)

- \(\quad\) HC3 formula (4.39):

reg wage education experience exp2 if (mnwf \(==1)\), vce \((\mathrm{hc} 3)\)

.jpg)

4.18 Measures of Fit

As we described in the previous chapter a commonly reported measure of regression fit is the regression \(R^{2}\) defined as

\[ R^{2}=1-\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\bar{Y}\right)^{2}}=1-\frac{\widehat{\sigma}^{2}}{\widehat{\sigma}_{Y}^{2}} . \]

where \(\widehat{\sigma}_{Y}^{2}=n^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\bar{Y}\right)^{2} \cdot R^{2}\) is an estimator of the population parameter

\[ \rho^{2}=\frac{\operatorname{var}\left[X^{\prime} \beta\right]}{\operatorname{var}[Y]}=1-\frac{\sigma^{2}}{\sigma_{Y}^{2}} . \]

However, \(\widehat{\sigma}^{2}\) and \(\widehat{\sigma}_{Y}^{2}\) are biased. Theil (1961) proposed replacing these by the unbiased versions \(s^{2}\) and \(\widetilde{\sigma}_{Y}^{2}=(n-1)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\bar{Y}\right)^{2}\) yielding what is known as R-bar-squared or adjusted R-squared:

\[ \bar{R}^{2}=1-\frac{s^{2}}{\widetilde{\sigma}_{Y}^{2}}=1-\frac{(n-1)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \widehat{e}_{i}^{2}}{(n-k)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\bar{Y}\right)^{2}} . \]

While \(\bar{R}^{2}\) is an improvement on \(R^{2}\) a much better improvement is

\[ \widetilde{R}^{2}=1-\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \widetilde{e}_{i}^{2}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\bar{Y}\right)^{2}}=1-\frac{\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}}{\widehat{\sigma}_{Y}^{2}} \]

where \(\widetilde{e}_{i}\) are the prediction errors (3.44) and \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\) is the MSPE from (3.46). As described in Section (4.12) \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\) is a good estimator of the out-of-sample mean-squared forecast error so \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) is a good estimator of the percentage of the forecast variance which is explained by the regression forecast. In this sense \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) is a good measure of fit.

One problem with \(R^{2}\) which is partially corrected by \(\bar{R}^{2}\) and fully corrected by \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) is that \(R^{2}\) necessarily increases when regressors are added to a regression model. This occurs because \(R^{2}\) is a negative function of the sum of squared residuals which cannot increase when a regressor is added. In contrast, \(\bar{R}^{2}\) and \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) are non-monotonic in the number of regressors. \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) can even be negative, which occurs when an estimated model predicts worse than a constant-only model.

In the statistical literature the MSPE \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\) is known as the leave-one-out cross validation criterion and is popular for model comparison and selection, especially in high-dimensional and nonparametric contexts. It is equivalent to use \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) or \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\) to compare and select models. Models with high \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) (or low \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\) ) are better models in terms of expected out of sample squared error. In contrast, \(R^{2}\) cannot be used for model selection as it necessarily increases when regressors are added to a regression model. \(\bar{R}^{2}\) is also an inappropriate choice for model selection (it tends to select models with too many parameters) though a justification of this assertion requires a study of the theory of model selection. Unfortunately, \(\bar{R}^{2}\) is routinely used by some economists, possibly as a hold-over from previous generations.

In summary, it is recommended to omit \(R^{2}\) and \(\bar{R}^{2}\). If a measure of fit is desired, report \(\widetilde{R}^{2}\) or \(\widetilde{\sigma}^{2}\).

4.19 Empirical Example

We again return to our wage equation but use a much larger sample of all individuals with at least 12 years of education. For regressors we include years of education, potential work experience, experience squared, and dummy variable indicators for the following: female, female union member, male union member, married female \({ }^{1}\), married male, formerly married female \({ }^{2}\), formerly married male, Hispanic, Black, American Indian, Asian, and mixed race \({ }^{3}\). The available sample is 46,943 so the parameter estimates are quite precise and reported in Table 4.2. For standard errors we use the unbiased HC2 formula.

Table \(4.2\) displays the parameter estimates in a standard tabular format. Parameter estimates and standard errors are reported for all coefficients. In addition to the coefficient estimates the table also reports the estimated error standard deviation and the sample size. These are useful summary measures of fit which aid readers.

Table 4.2: OLS Estimates of Linear Equation for \(\log (\) wage \()\)

| \(\widehat{\beta}\) | \(s(\widehat{\beta})\) | |

|---|---|---|

| Education | \(0.117\) | \(0.001\) |

| Experience | \(0.033\) | \(0.001\) |

| Experience \(^{2} / 100\) | \(-0.056\) | \(0.002\) |

| Female | \(-0.098\) | \(0.011\) |

| Female Union Member | \(0.023\) | \(0.020\) |

| Male Union Member | \(0.095\) | \(0.020\) |

| Married Female | \(0.016\) | \(0.010\) |

| Married Male | \(0.211\) | \(0.010\) |

| Formerly Married Female | \(-0.006\) | \(0.012\) |

| Formerly Married Male | \(0.083\) | \(0.015\) |

| Hispanic | \(-0.108\) | \(0.008\) |

| Black | \(-0.096\) | \(0.008\) |

| American Indian | \(-0.137\) | \(0.027\) |

| Asian | \(-0.038\) | \(0.013\) |

| Mixed Race | \(-0.041\) | \(0.021\) |

| Intercept | \(0.909\) | \(0.021\) |

| \(\widehat{\sigma}\) | \(0.565\) | |

| Sample Size | 46,943 |

Standard errors are heteroskedasticity-consistent (Horn-Horn-Duncan formula).

As a general rule it is advisable to always report standard errors along with parameter estimates. This allows readers to assess the precision of the parameter estimates, and as we will discuss in later chapters, form confidence intervals and t-tests for individual coefficients if desired.

The results in Table \(4.2\) confirm our earlier findings that the return to a year of education is approximately \(12 %\), the return to experience is concave, single women earn approximately \(10 %\) less then single men, and Blacks earn about \(10 %\) less than whites. In addition, we see that Hispanics earn about \(11 %\) less than whites, American Indians \(14 %\) less, and Asians and Mixed races about \(4 %\) less. We also see there

\({ }^{1}\) Defining “married” as marital code 1,2 , or \(3 .\)